Why we need to get back to Venus – Astronomy Magazine

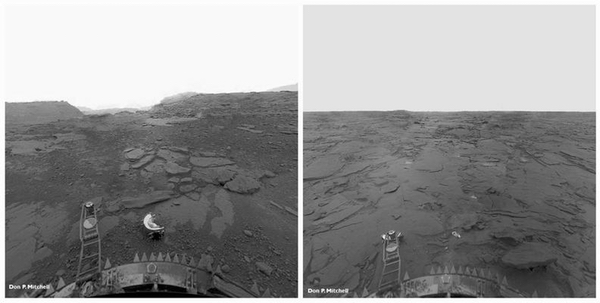

The surface of Venus as seen in these reprocessed perspective image panoramas from the Soviet Venera 13 lander.

Don P. Mitchell, CC BY-SA

The current scientific view of Venus holds that, at some point in the past, the planet had much more water than its bone-dry atmosphere suggests today – perhaps even oceans. But as the Sun grew hotter and brighter (a natural consequence of aging), surface temperatures rose on Venus, eventually vaporizing any oceans and seas.

With ever more water vapor in the atmosphere, the planet entered a runaway greenhouse condition from which it couldn’t recover. Whether Earth-style plate tectonics (where the outer layer of the planet is broken into large, mobile pieces) ever operated on Venus is unknown. Water is critical for plate tectonics to operate, and a runaway greenhouse effect would effectively shut down that process had it operated there.

But the ending of plate tectonics wouldn’t have spelled the end of geological activity: The planet’s considerable internal heat continued to produce magma, which poured out as voluminous lava flows and resurfaced most of the planet. Indeed, the average surface age of Venus is around 700 million years – very old, certainly, but much younger than the multi-billion-year-old surfaces of Mars, Mercury or the Moon.