Why it Failed: The Space Shuttle – Aeronautics Online

This article is part of the Why it Failed series at Aeronautics, which discusses aircraft and spacecraft that didn’t take off as well as they were expected to.

The Space Transportation System (more commonly known as the space shuttle) was the first partially reusable launch system. It flew 135 missions from 1981 to 2011, with five orbiters, Columbia, Challenger, Discovery, Atlantis and Endeavour, and delivered over 400 people to space.

However, by the shuttle’s retirement in 2011, only three of the crafts remained. Challenger had been infamously destroyed in 1986 during the launch of STS-51L (the 25th shuttle flight), and Columbia had broken up on re-entry during STS-107 (which led to the shuttle’s retirement). In the two events, the shuttles killed seven astronauts each, while Columbia also killed two technicians (through lack of oxygen) during construction.

Before continuing this analysis, it is important to remember that the shuttle was an important step forward, and did amazing things while flying. It delivered payloads ranging from space station modules to the Hubble Space Telescope and contributed greatly to our scientific knowledge while bringing more people into space than ever before.

However, the shuttle failed spectacularly in its main goal: to make space travel safe and affordable. By the end of the program, it cost around 2 billion dollars to launch seven people along with a meagre 20 tons of payload, all the while risking a 1-in-70 chance of a failure causing the deaths of everyone on board. What caused this?

In hindsight, it was obvious that the shuttle would be more expensive than expendable launchers of the time. The mix of compromise, lack of funding, the limitations of 1970s technology, and the inability to upgrade or improve the system led to the shuttle’s downfall.

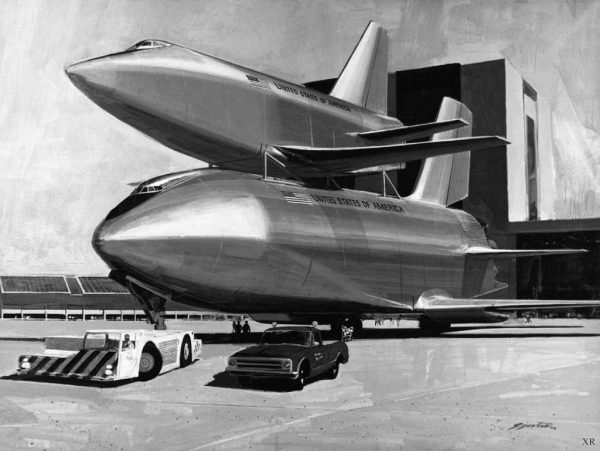

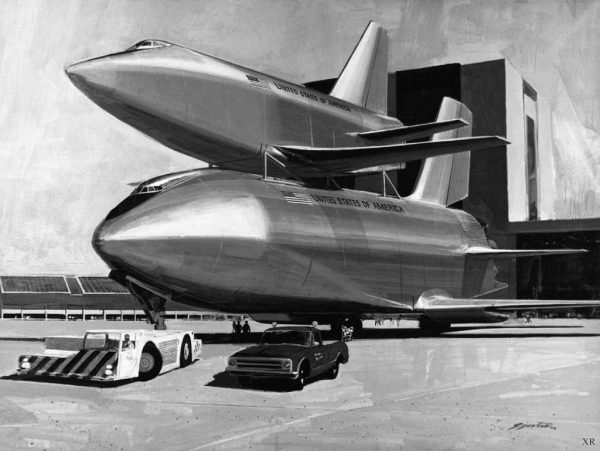

When the Shuttle was first being advocated within NASA, it was much different, with two completely reusable stages and a relatively small payload bay. This proposal did indeed have the potential to be much cheaper than anything before, with a simple re-entry protection system similar to the X-15 (the first true spaceplane) and the recovery of all hardware.

But this was the 1970s, where the Vietnam War, economic downturn and anti-technology movement were primary factors in American budgets and decision-making. The Apollo Program was already being strangled in its crib, with the last three lunar landings cancelled and it’s successor, the Apollo Applications Program, being stillborn on arrival. In this environment hostile to ‘frivolous’ expenditures such as manned space travel, funding was scarce if not non-existent. In fact, there was a serious consideration to just abandon human spaceflight altogether by politicians and then-president Nixon, especially after the near-failure of Apollo 13.

This meant that any fully reusable shuttle system cost far too much to develop, even if it would provide substantial savings later on. NASA was given a cost cap of 5 billion dollars, while the two-stage reusable system would have likely cost 10 billion to develop, far too high for the Office of Management and Budget.

In addition to budget woes, an evaluation by a firm called Mathematica calculated that, in order to make reasonable savings over an expendable or partly-expendable shuttle, a fully reusable system would have to take 57 flights a year! In order to reach this ridiculous flight rate – we currently make 60 orbital flights a year – NASA would need all the payloads it could get, including those for military purposes. Enter the Air Force.

The Air Force was happy to collaborate with NASA, as long as they could dictate the payload weight and size the shuttle could bring to orbit, along with how far it could move its landing site on its return. This meant a large and relatively heavy payload bay combined with a large wing area, making an X-15-esque re-entry system impossible. In order to make up for this, a ceramic ‘Tile Protection System’ was needed to protect the orbiter. This TPS would later prove to be one of the most difficult and time-intensive parts of reusing the space shuttle, with the entire system taking tens of thousands of man-hours to refurbish. In addition to this, tiles would fall off during launch, something that was only aggravated by insulation from the main fuel tank or boosters hitting the ceramic.

In 2003, 17 years after the Challenger disaster, Columbia would be destroyed by this very process. A piece of foam the size of a briefcase created a hole in the TPS, which led to a burn-through of the shuttle’s left wing and its subsequent destruction. This isn’t even counting the dozens of times there were foam impacts on shuttles, one of whom almost led to the loss of Atlantis on STS-27, only the second flight after Challenger crashed. The flight was only saved by a metal strut under the impacted area, which required extensive maintenance.

However, this was still far into the future, and the OMB was still unhappy with the shuttle’s development cost. To meet budget requirements, NASA had to sacrifice the shuttle’s two-stage reusable structure for an expendable fuel tank and boosters (the so-called “butterfly on a bullet” architecture). However, this was not enough.

In a decision that would echo into the future, the decision was made to use solid boosters. These could not be shut down, making a safe in-flight abort impossible, and were much harder to re-use. This was known at the time, and in a frightening case of precognition, a study was released predicting that if there was a case of burn-through of the solid boosters, it could lead to the loss of a shuttle and its crew; precisely the event which would occur with Challenger 14 years later.

Finally, the predicted development cost of the space shuttle had finally fallen beneath the 5 billion dollar mark, and the OMB endorsed the final configuration of the space shuttle. In 1972, President Nixon announced the Shuttle Program and declared it the way of the future. Despite the numerous cutbacks and compromises in the shuttle design, it was still expected to fly weekly only a couple years after its first flight. This expectation would contribute to the Challenger disaster, as the urgency felt by NASA to increase flight rates and limit launch delays caused the go-ahead for launch to be given, even after engineers begged for the flight to be delayed.

In conclusion, it was the requirement to limit development costs and have a large payload bay that made the shuttle fail. To achieve all in the 1970s, while limiting the cost and danger of space travel, was impossible. Instead of this, a compromise was made that permanently crippled any chance of a safe and cost-effective reusable spacecraft. It was just a bridge too far.

Featured image courtesy of NASA