What’s the Point of the James Webb Space Telescope? – Space.com

Paul M. Sutter is an astrophysicist at The Ohio State University, host of Ask a Spaceman and Space Radio, and author of “Your Place in the Universe.” Sutter contributed this article to Space.com’s Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope is (currently) scheduled to launch in March of 2021, after years of delays and billions of dollars spent over budget. While it’s easy to argue that all that time and money has been wasted, this observatory will be the premiere and undisputed champion of infrared wavelengths, giving us unparalleled access to corners of the universe currently inaccessible.

If we want to learn new things about everything from the first galaxies to the chance for life on other planets, the roughly $9.7 billion James Webb is our only hope.

Related: Building the James Webb Space Telescope (Gallery)

No chill

While the James Webb Space Telescope (“JWST” to those in the know) is heralded as the “successor” to NASA’s storied Hubble Space Telescope, it kind of isn’t. The Hubble is primarily an optical telescope, capturing wavelengths of light similar to the range that the human eye does, and extending past that a little bit into the infrared and ultraviolet (UV) portions of the electromagnetic spectrum. In essence, the Hubble is a giant orbiting space eyeball, delivering stunning pictures that you would see, if your optic nerves were similarly equipped.

But the JWST is different. It will be observing entirely in the infrared, barely scratching the deepest possible reds that a human can see. In other words, the JWST will be studying a universe that is largely invisible to human experience.

One of the major reasons that the JWST is designed to be an infrared scope is that infrared astronomy is, in general, really hard to do from the surface of the Earth. Light pollution is the bane of astronomers, who need their skies crystal-clear and perfectly dark to do their detailed observations and measurements.

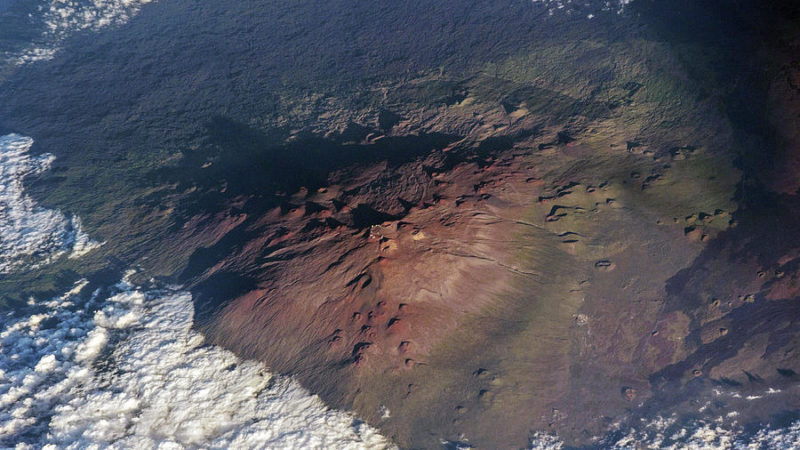

And infrared light pollution comes from many different places. Basically, anything warm. Which is, basically, everything. Human bodies generate 100 watts of infrared radiation. The Earth itself is pretty warm, glowing strongly in infrared bands. Even the telescope itself, if it’s at room temperature, is aglow in the infrared.

It’s not that we can’t do infrared astronomy from the ground, it’s just that it’s frustratingly hard.

Hence, space.

Far from home

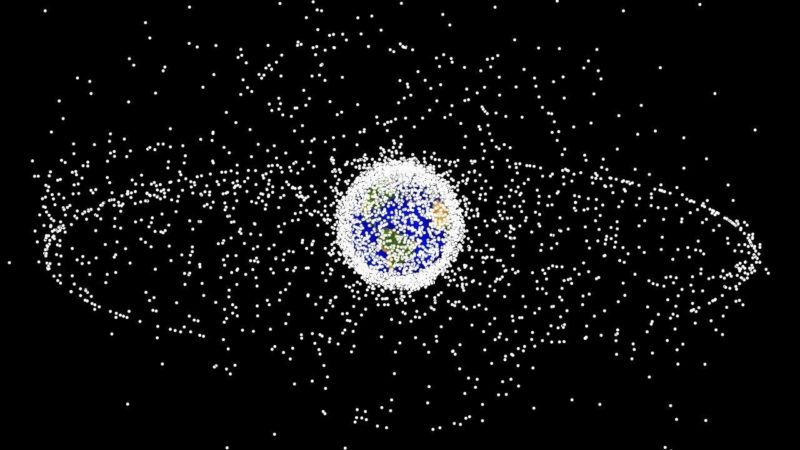

The JWST will operate about 1 million miles (1.5 million kilometers) from the Earth, to get it safely far away from our warm, infrared-glowing planet. But even still, there’s the sun to contend with. Ever sit outside on a nice summer day, feeling the warmth of our sun on your skin? Yeah, that’s infrared radiation, pumped out by the bucketful. And even a million miles away from the Earth, the sun is still a little bit toasty.

To combat this, designers of infrared space telescopes have a couple options. The most common choice is to use an active cooling system, chilling down the telescope to the temperatures needed to properly observe infrared wavelengths. This is great, and utilized by previous infrared space telescopes, but it does limit their lifespans. No more coolant = no more astronomy.

So instead the JWST will deploy a giant, expensive space umbrella, 72 feet (22 meters) long and 36 feet (11 m) wide, made of five layers of extremely reflective material, each layer thinner than a human hair. This massive “sunshield” will keep the telescope itself in constant shade, somewhere south of minus 370 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 223 degrees Celsius), which is ideal for the infrared wavelengths it will be studying.

Although, just for fun, one of the instruments onboard will be chilled with an active cooling system to below minus 433 Fahrenheit (minus 258 C ), which will allow it to access some even longer infrared wavelengths.

Related: NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope Passes Vital Sun Shield Test

Behold the science

All in all, the JWST is massive. In fact, it’s so big that it shouldn’t be able to fit on a rocket. Besides the gargantuan sunshield, the primary mirror will be 21 feet (6.5 m) across, which is far wider than any rocket fairing currently in use. Duct-taping the mirror to the side of the rocket isn’t exactly a workable solution, so instead the clever NASA engineers broke the mirror into 18 smaller hexagonal sections, which will be tucked and folded into the rocket (along with the folded-up sunshield and the rest of the telescope itself).

If everything goes right, just a few days after launch the JWST will head to its observing point, unfold, and start staring.

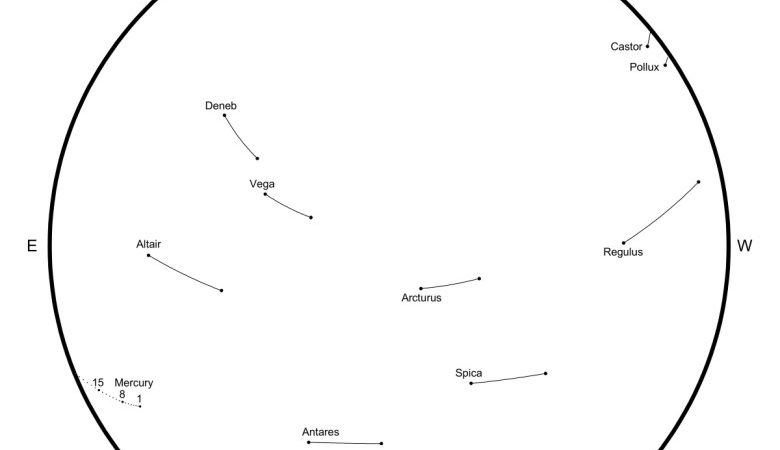

And what it will see will be — and I’m not using this word lightly — remarkable. One of its main targets will be the early universe, when our cosmos was just a few hundred million years old. The first stars and galaxies to appear on the cosmic scene blazed brightly in the visible spectrum, but over the course of the past 13 billion years the universe has expanded, stretching that light out of the visible range and down into the infrared — right in the sweet spot of the JWST’s design parameters.

Since we have no images at all from the epoch of the first stars and galaxies (known colloquially as the “cosmic dawn“) this will be our first-ever view into this important age in the history of the cosmos.

Closer to home, the JWST will study anything cool in the cosmos, from protoplanetary disks around newborn stars to molecular clouds, comets, Kuiper Belt objects and more.

And JWST will use a specialized device to block out light from some distant stars, enabling the observatory to snap pictures of any objects orbiting those stars — like exoplanets. Those planets will be glowing in the infrared, and the light from those planets will be modified by the chemicals and elements in their atmospheres, chemicals and elements which might be signs of life.

From ET hunter to cosmic-dawn revealer, the JWST will certainly be worth the wait.

Learn more by listening to the episode “Is the James Webb worth the wait?” on the Ask A Spaceman podcast, available on iTunes and on the Web at http://www.askaspaceman.com. Thanks to @SethDSanders, @hhyech, White I., and Veljo U. for the questions that led to this piece! Ask your own question on Twitter using #AskASpaceman or by following Paul @PaulMattSutter and facebook.com/PaulMattSutter.