What’s Hotter Than the Surface of the Sun? The Solar Corona – Astronomy Magazine

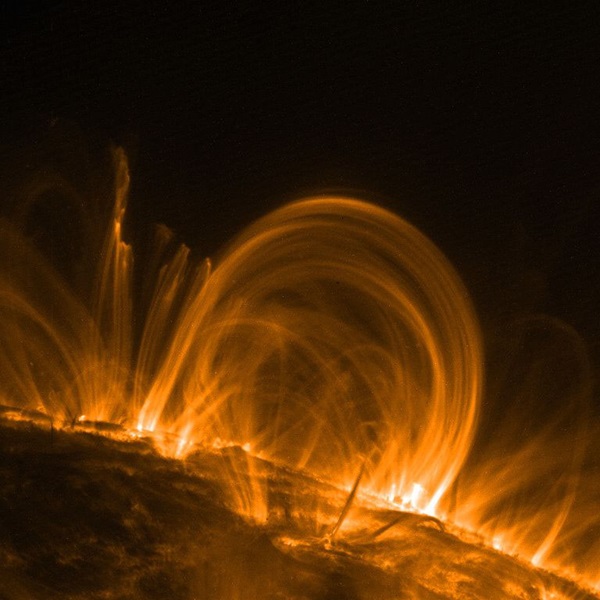

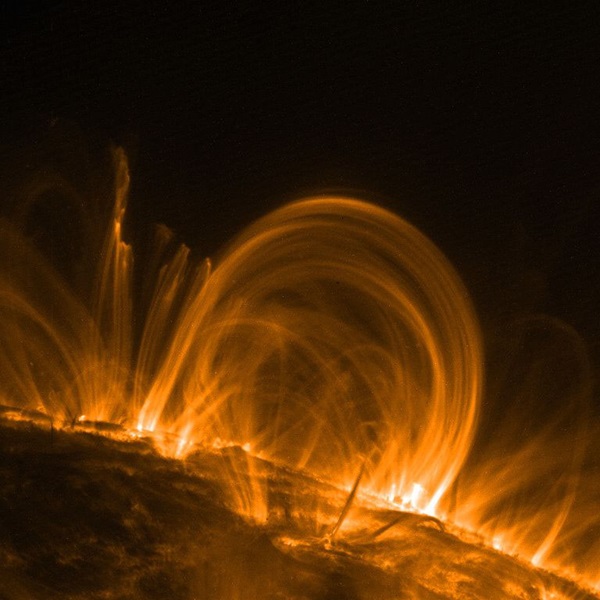

Coronal loops, seen in this ultraviolet image from NASA’s TRACE satellite, form when plasma in the Sun’s corona coalesces around arcs of magnetic field lines billowing from the Sun’s surface. The cluster of loops shown here are blazing hot and gigantic, measuring 30 or more times the diameter of Earth.

M. ASCHWANDEN ET AL (LMSAL) / TRACE / NASA

Both ideas are phenomenally difficult to test. Computer simulations and calculations suggest that whatever mechanisms drive energy into the corona likely do so on scales that are too small and too fast to see from afar. Ground truth will probably have to come from a spacecraft snuggled up close to the sun. That’s where NASA’s Parker Solar Probe comes in.

Parker launched in 2018 on a seven-year mission to repeatedly dive through the corona. With every orbit, a gravitational nudge from Venus inches the spacecraft ever closer to the sun. The probe will eventually settle into an orbit just over 6 million kilometers from the sun’s surface — seven times closer than any spacecraft before.

At that distance, the sun-facing side of the spacecraft will get roasted to over 1,300 degrees Celsius, its suite of instruments protected by an 11-centimeter-thick carbon-composite shield. (Though the corona has a very high temperature, its particles are relatively sparse — this low density keeps the craft from getting as hot at the corona itself. See why here.)

From its unique vantage point deep inside the corona, Parker is already snapping pictures, measuring electromagnetic fields and counting particles.

With data from the first two orbits in hand — in which Parker flew just 24 million kilometers from the sun — the science team is preparing to publish initial results in a handful of papers this fall. Several dozen more will follow in January. While the team remains tight-lipped about what the spacecraft has seen, their excitement is palpable.

“We’re seeing phenomena that we never even imagined we would see,” says project scientist Nour Raouafi.

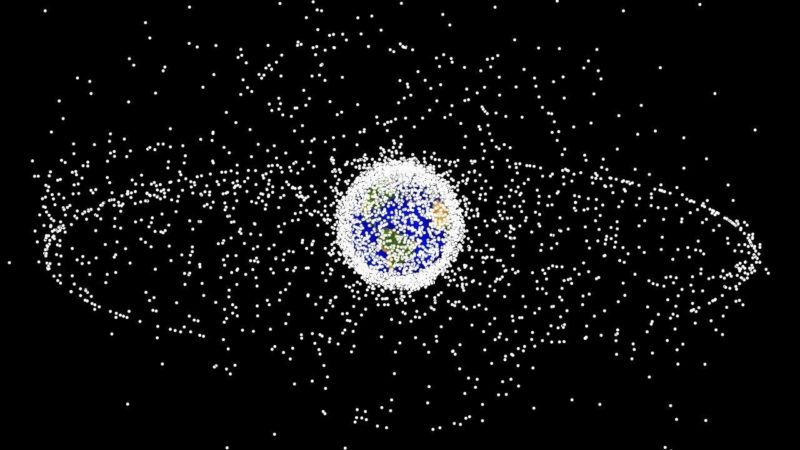

The Sun’s corona gets trapped by magnetic field lines, which are likely responsible for heating the corona to millions of degrees. Far from the Sun, some of the corona escapes to become the solar wind, a steady stream of charged particles that washes over all the planets.

NASA’S GODDARD SPACE FLIGHT CENTER / LISA POJE

Nicola Fox, former project scientist and current head of NASA’s heliophysics division, concurs: “Even just in our first couple of orbits, we have pulled down data that was unexpected, that had features in it that definitely could … pave our way to piecing together the puzzle of the coronal heating.”

In the coming months, Parker will be joined by two other sun-loving projects. Later this year, a new solar telescope in Maui will open for business. The Daniel K. Inouye Solar Telescope will snap images sharp enough to make out details on the surface of the sun about 30 kilometers across — small enough to reveal the building blocks of the magnetic field, says Raouafi.

Then in February, the European Space Agency will launch Solar Orbiter, a mission to soar out of the plane of the solar system and look “down” on the sun. Except for the now-defunct Ulysses probe, which had no camera onboard, no spacecraft has studied the sun from this angle. From high above the solar system, Solar Orbiter could help researchers piece together the three-dimensional structure of features in the corona and solar wind.

With these three missions working together, researchers hope to crack some of the coronal mysteries that could enrich our understanding of the Earth-sun interaction.

As the only star in the universe that we can see up close, the sun can teach scientists about how more distant stars may interact with nearby worlds. Scientists believe that solar winds stripped Mars of its protective atmosphere, and other stars may act likewise. “It’s like having a lab in your backyard,” says Fox.

“This is really the most exciting time to be a solar physicist,” says Raouafi. “I believe the next decade will be revolutionary in terms of understanding how the sun and [its] atmosphere work.”

10.1146/knowable-092319-1

Christopher Crockett is a freelance science journalist in Arlington, Virginia, focused on all things astronomy, physics and Earth science.

This article originally appeared in Knowable Magazine, an independent journalistic endeavor from Annual Reviews. Sign up for the newsletter.