The path forward for astronomers and native Hawaiians – Big Think

In 2015, the astronomy community was excitedly anticipating the next generation in ground-based, optical astronomy. After more than 20 years of 10-meter class telescopes being the largest and most powerful in the world, a trio of 30-meter class telescopes were slated for construction: two in Chile and one in Hawaii. While the Giant Magellan Telescope and the European Extremely Large Telescope were both overwhelmingly supported by the indigenous population, Hawaii’s proposed Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT) — like many telescopes atop Mauna Kea before it — faced significant protests and opposition from native Hawaiians, who cited many concerns and injustices that dated back decades or even centuries.

In one of the worst public relations move in all of science history, a number of senior astronomers circulated a message that read, in part, “The Thirty-Meter Telescope is in trouble, attacked by a horde of native Hawaiians who are lying about the impact of the project on mountain and who are threatening the safety of TMT personnel. Government officials are supporting TMT’s legality to proceed but not arresting any of the protestors who are blocking the road.” The letter served to galvanize not only native Hawaiians against the TMT and the status quo of astronomy on Mauna Kea in general, but also indigenous communities across the globe and a large fraction of the astronomy community as well.

Is there a viable path forward for native Hawaiians and astronomers? Can both communities mutually benefit from collaborating together? It cannot happen without mutual respect and understanding, but that’s a goal that really should be well within reach. Here’s what everyone should know.

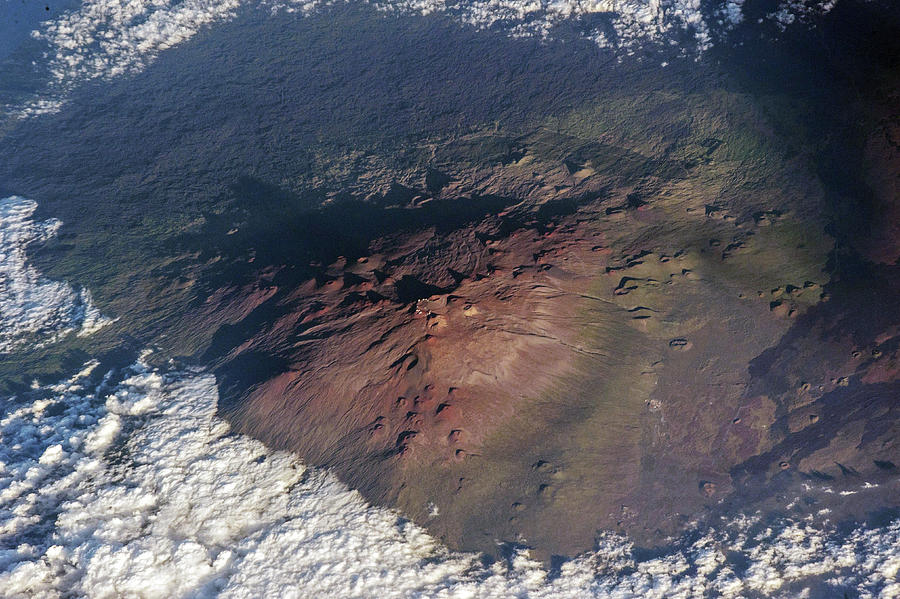

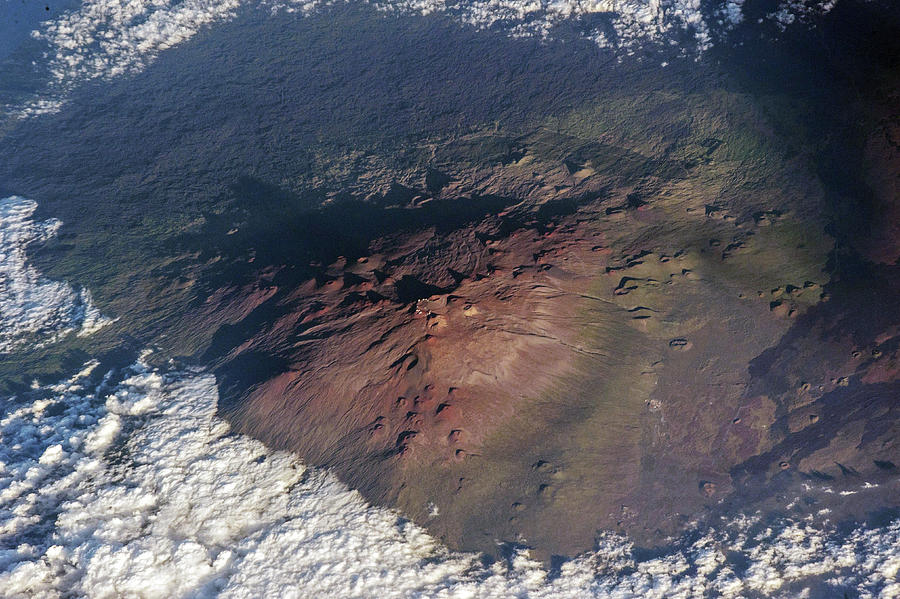

Even as viewed from space, captured here from the International Space Station, Mauna Kea’s summit is an incredibly impressive site. From sea level, it rises up 4,205 meters (13,800 feet) above the oceans, but is thought to be completely extinct, having last erupted more than 4000 years ago.

First off: Hawaii has an incredibly long, storied, and ancient history that dates back thousands of years. Settled by Polynesian voyagers when the Roman Empire was still standing, the great King Kamehameha unified the Hawaiian islands during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. That history — preserved in artifacts, language and song — has been mostly overwritten (and subsequently ignored and even denied) by Europeans and Americans who arrived subsequently.

Throughout the 19th century, missionaries, traders, whalers, and businessmen came to Hawaii, bringing diseases and exploitation with them. The native population shrank from a late-18th century peak of 300,000 to a mid-19th century low of just 70,000. Sugar plantations were the mainstay of the Hawaiian economy, controlled by American colonists. In 1893, the U.S. government staged a coup, overthrowing Queen Lili’uokalani, imprisoning her and forcing her to abdicate. This action remains one of only five in all of history that the U.S. government has officially apologized for.

That apology, of course, did not result in a return of self-government or self-determination. Hawaii was annexed by the United States in 1898, and became the Territory of Hawaii, with a United States Governor, in 1900. Native Hawaiians have continuously had to battle to keep their culture, history, and language intact, and to this day still suffer from a lack of representation in their own self-government.

This photo shows the occupation of Arlington Hotel grounds during the overthrow of Queen Lili’uokalani in 1893. Despite the official story told at the time by the soldiers and their commanders, history has generally recognized that this was an act of aggression and imperialism that has subsequently been condemned nationally and internationally.

When astronomy came to Hawaii, it had only recently been admitted to the United States as the 50th (and still most recently added) state. Many had previously noted a trio of remarkable conditions at the summit of the Big Island: the peak of the extinct Mauna Kea.

- The peak, at 4,207 meters (13,800 feet) above sea level, is one of the highest-altitude but least dangerous mountain summits.

- The air at the summit is typically cool, dry, and still, with mostly clear and rarely cloudy skies.

- And Mauna Kea has (and had) extremely low levels of light pollution, especially when compared to other major astronomical sites on the North American and European continents.

After Hawaii gained statehood in 1959, the summit of Mauna Kea was opened up for astronomy. The deal, established by the State in 1968 and written to last for 65 years (until 2033), was that astronomers would get access to the mountain and the summit, and in return, the University of Hawaii would get 15% of the observing time on all telescopes that would be built atop the mountain, and would also provide stewardship of the lands and waters.

What about the community of native Hawaiians? They got $1 per year: the cost of the State-ordered lease of the land.

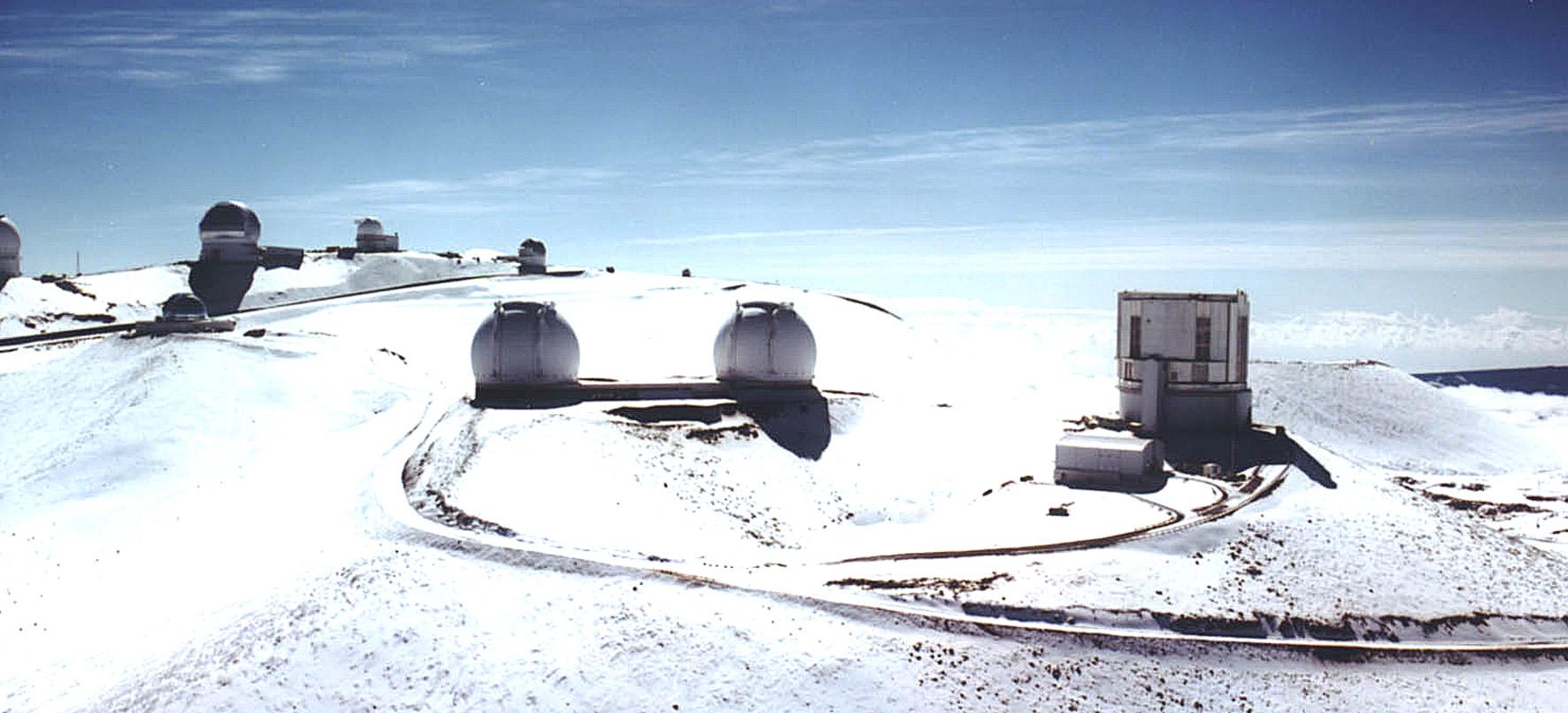

This facility photo of the Subaru Telescope and its nearby vicinity at the summit of Mauna Kea shows a common occurrence during the winter months: snow at the summit. The Subaru Telescope at right, is next to the twin Keck Telescopes, with other observatories visible farther to the left in this image.

Telescopes were placed atop the mountain almost immediately, beginning with the UH 2.2 meter telescope in 1970. Were the lands and waters managed properly by the University? Not at first: in 1998, 30 years into the lease, a State audit determined that the University’s management was wildly insufficient, with the University acknowledging and apologizing for its shortcomings, and taking substantial, well-documented steps to remedying the situation. Some ~$12 million, annually, is now devoted towards stewardship and land management from the University.

Were opportunities created for Hawaiian citizens and residents? Again, not at first, but the past ~25 years have begun to show a remarkable set of steps, including:

- Outreach efforts to bring Hawaiians, including school children, to the observatories and the visitor’s center on Mauna Kea.

- The establishment of the Maunakea scholars program, which serves to provide astronomy opportunities to young people in Hawaii.

- The 2006 creation and subsequent expansion of the ‘Imiloa Astronomy Center, which attracts more than 1 million visitors annually: 85% of which are from Hawaii.

- Creating the Journey Through the Universe program, which provides classroom visits, teacher workshops, and other educational opportunities in Hawaiian classrooms throughout the year.

These are important steps that are certainly pointing in the right direction, but almost all of these efforts predominantly benefit the residents of Causasian and Asian descent, and only rarely reach the native Hawaiian population.

The Imiloa Astronomy Center contains a wide variety of planetarium shows, activities and educational opportunities for children and adults, and a spectacular set of exhibits that highlight native Hawaiian history, culture, and the relationship of the Hawaiian people with both the stars and the darkness. Despite this, most native Hawaiians have never visited the Imiloa Astronomy Center. Astronomers must work harder to send the message that astronomy is for everyone.

Most working astronomers today recognize that even today, the astronomy community continues to benefit from a set of legacy agreements, established during a much more colonialist time in our country’s and world’s history, that are inherently unfair to native Hawaiians. However, the question that most of them — particularly the more senior astronomers in the field — continue to ask is completely wrongheaded. Instead of asking, “how much do we need to give up in order to get permission to build the TMT on Hawaii,” the question astronomers should be asking is one of restorative justice: how can we behave, today, in a way that serves to right the past wrongs and build a fairer, more equitable future?

That latter question was the topic of a moderated discussion at the American Astronomical Society’s 241st meeting in Seattle, WA in January of 2023. During that discussion, led by ‘Imiloa director Ka’iu Kimura and panelists Rich Matsuda, Dr. Noe Noe Wong-Wilson, and John Komeiji, a heavy emphasis was placed on the Hawaiian concept of Ho’oponopono, which focuses on conflict resolution and in particular on the steps of acceptance, reconciliation, and renewal. In short, it’s about how to right past wrongs and move forward: not to cast blame or punish the wrongdoers, but for all sides to make common cause and work together for the benefit to all. The idea, as described by Rich Matsuda, is to find “a Hawaii way” to resolve this conflict and repair old wounds.

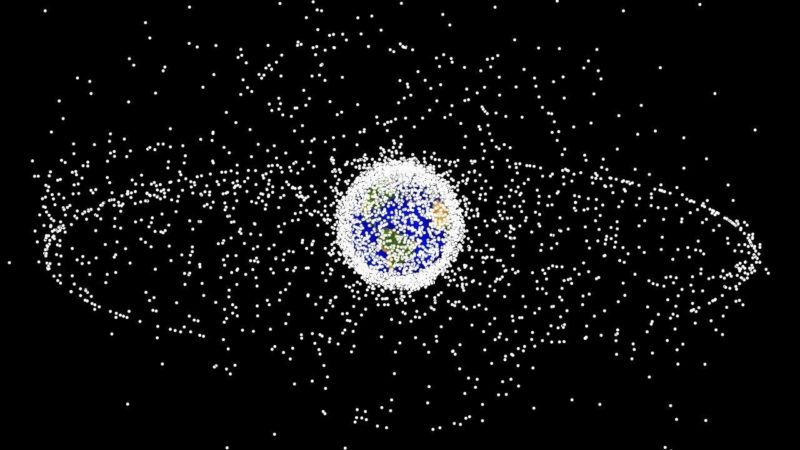

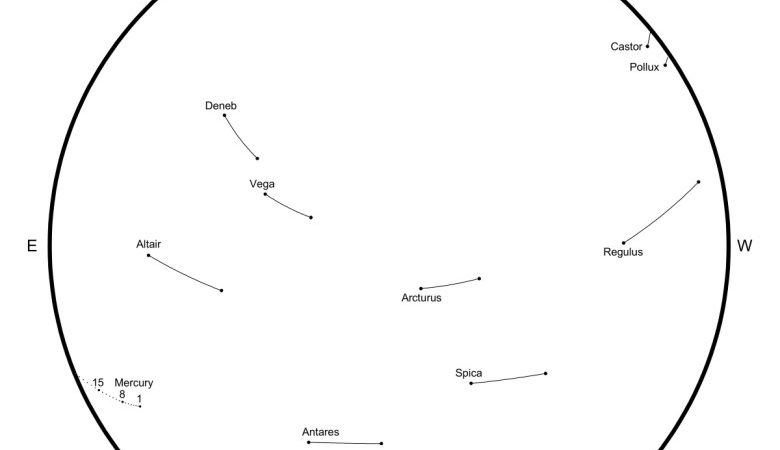

Although the Keck Observatories on the summit of Mauna Kea offer some of the best views of the universe from Earth, they are not immune to the effects of satellites. As of early 2023, more than 50% of all active satellites have been launched since 2019 and are owned and operated by SpaceX’s Starlink. Satellite pollution of our night skies is a serious issue that astronomers and native Hawaiians can, and should, make common cause with one another to fight.

To a western audience, the concept of Ho’oponopono and the path towards resolving longstanding conflicts touches the concept of consent (particularly as applied to romantic relationships), as well as conflict resolution strategies traditionally taught as part of relationship/couples counseling.

For those of us who came-of-age in the 1990s and earlier, consent was a murky concept, and one that was rarely discussed openly and with words. We relied on non-verbal cues and communication to navigate what was and wasn’t okay, and normally a verbal conversation would only ensue when a boundary had been crossed or something had gone wrong with the interaction. Today, the much healthier strategy of requiring that all parties involved give an enthusiastic, unambiguous “yes” or “green light” to go ahead, otherwise we recognize that consent has not been obtained, is far healthier.

Without an enthusiastic, overwhelming “yes” from the native Hawaiian community stating, “yes, we should build the TMT atop Mauna Kea,” the astronomy community generally recognizes that we should not proceed with construction.

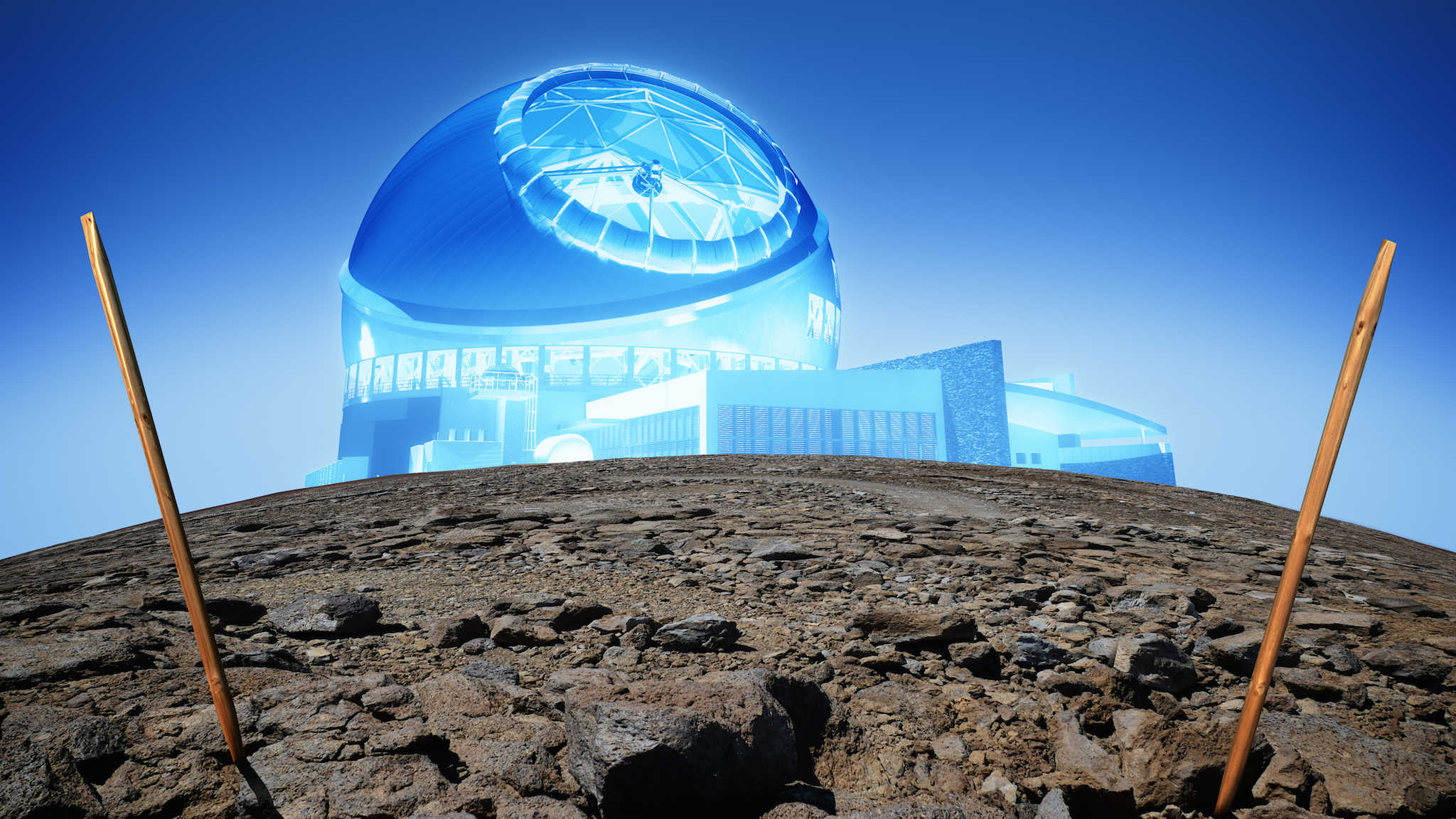

This computer-generated outline of what the TMT would look like at the “ground-breaking” site as it looked in October of 2014 should never come to fruition unless the overwhelming majority of native Hawaiians enthusiastically consent to the terms of its construction.

When it comes to conflict resolution in relationships — although this certainly takes many different forms — many therapists have focused on three steps: recognition, remorse, and repair. They break down as follows.

- Recognition: understanding what you did and/or what you failed to do, and how that negatively impacted the other person/party. This includes taking ownership of either your actions or your inactions, and an ability to state “I did this thing and I recognize that it was hurtful and/or caused injury to you.”

- Remorse: a genuine expression of sorrow and empathy for the wounds that the aggrieved person/party has experienced. It often goes hand-in-hand with recognition, and the expression of remorse must be for what you did and didn’t do, not for what the other person/party feels. You are sorry for what you did; you cannot be sorry for what the other person felt or how they interpreted your actions.

- Repair: this is, arguably, the most meaningful step, where you take substantive action to immediately cease all prior behavior that you recognize did harm, and to instead replace it with helpful, constructive behavior. You actively work to repair whatever wounds your actions and/or negligence caused, and to ensure that, instead of being worse off because of your previous negative impacts, the other person/party winds up better off because of your reparative actions.

The Hawaiian canoe, Hokulea, was traditionally designed and was indeed capable of sailing across oceanic waters. Native Hawaiians were present on Hawaii for upwards of 1000 years before Captain Cook “discovered” the islands in the late 1700s, but it was only very recently that American and European historians have accepted this fact.

So what does “doing it right” look like, both for the astronomy community and the native Hawaiian community?

There are a few lessons to be learned from looking at a couple of (relative) success stories: of astronomical observatories in Chile and of radio astronomy (and the now-defunct Arecibo observatory in particular) on Puerto Rico. In at least one of these places:

- the land that the astronomical observatories are built on is stewarded by the indigenous people who are native to the area,

- the observatories themselves are managed and directed by citizens who are native to the area,

- the universities and research institutes that are (among) the primary users of the observatories boast many full-time faculty and staff that are native to those lands,

- there is a healthy pipeline of students native to the area, including among the indigenous population, that get to use the facilities,

- there is a path for native students to become professionals working in the field of astronomy where the observatories are located,

- and that the beneficiaries of the astronomy community’s outreach efforts aren’t limited by geography or socio-economic status, but rather extend to the entire population of the country/territory.

Travel the Universe with astrophysicist Ethan Siegel. Subscribers will get the newsletter every Saturday. All aboard!

It’s vital to note that none of these statements are true for the community of native Hawaiians, on whose land the Mauna Kea observatories all operate.

While many Hawaiian residents and visitors can experience the incredible beauty and wonder of Mauna Kea, only those with the means, time, and resources to access Mauna Kea are the ones who get to experience it.

Even looking at the historical injustices that have been perpetrated against the native Hawaiian people and the present-day inequities that native Hawaiians face, there are reasons to be hopeful that the astronomy community will, at long last, Ho’oponopono: to cause things to move back into balance. One action that has been taken, and that was announced at the American Astronomical Society’s 241st meeting, is that the stewardship of Mauna Kea will indeed be transferred over to native Hawaiians in no greater than the next 5 years. This is in progress right at the present moment.

But there are other actions that could and should be taken, including:

- prioritizing the advancement of native Hawaiians within astronomy at all levels,

- extending astronomical outreach efforts to reach all Hawaiians, not just those in the largest population centers or nearest to the astronomical facilities,

- bringing star parties and the history of stellar navigation in Polynesian voyaging to all schools and communities throughout Hawaii,

- including native Hawaiians in all policymaking decisions, including in the preservation of dark, quiet, and pristine skies and in the efforts to reduce the growing problems of both light and satellite pollution,

- creating more opportunity for native Hawaiians to benefit from programs like Maunakea scholars, rather than the most socioeconomically privileged Hawaiians that primarily benefit from it today,

- and creating follow-up opportunities for students who enjoy and are inspired by programs such as Journey Through The Universe, rather than having it be just a once-per-year visit to their school.

It’s up to all astronomers who live, teach, research or observe on Hawaii to not only take these actions, but to impart to their students, mentees, and colleagues the importance of making things right for all.

The summit of Mauna Kea is home to many of the greatest astronomical observatories ever to exist on Earth. The summit is also an inextricable part of the native Hawaiian culture, history, and heritage that has historically been erased by US and European interests. Here, the domes of the Subaru Telescope (L), the twin W. M. Keck Telescopes (center), and the NASA Infrared Telescope Facility (R) all stand out.

The main takeaway for astronomers is this. The indigenous community of native Hawaiians has been speaking for a long time, and it’s far overdue for us to not only listen to what they’re saying, but to hear it and understand their grievances. It isn’t just about what astronomy has or hasn’t done; it’s also about a history of wrongdoing where no one has sufficiently worked to right those wrongs. Our entire professional community has benefitted immeasurably from astronomy’s presence on Hawaii, and now is the time to make sure that Hawaii in general — and native Hawaiians in particular — benefit from our presence there as well. (This especially should include astronomers at the Institute for Astronomy at the University of Hawaii-Honolulu: historically the greatest beneficiaries of the original 1968 agreements that are still in place, and one of the most notoriously productive yet simultaneously toxic academic environments in all of astronomy.)

Most important is this: the efforts the astronomy community makes towards reparative actions to the Hawaiian community should be independent of any decisions made about the TMT. We must make it clear that, at any time, native Hawaiians are free to say “no,” and to withdraw consent for any new or even any existing telescopes and observatories, and the astronomical community will accept that outcome. The goal should be to foster a long-term and positive spirit of collaboration in preserving, protecting, and exploring all that’s out there to behold in our shared night sky: now, and for generations to come.