Technology Brings Dementia Detection to the Home – Alzforum

The past decade has seen increasing use of technology in dementia research. Computer games that provide cognitive training have become part of prevention studies, and trialists are working to move cognitive testing out of the clinic and into everyday life, replacing pen and paper with tablets and smartphones. A plethora of new tools are being tried out. Alas, adherence is a problem and researchers grapple with how to get people to check in and complete tests day after day. At the Technology and Dementia Preconference, held in advance of the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference on July 14-18 in Los Angeles, scientists discussed roadblocks and efforts to boost engagement. They are transforming cognitive tests into fun games, and dangling bonuses to encourage participation. As an alternative, passive monitoring equips seniors and their homes with sensors to track activity around the clock, and to flag changes that signal dementia. Part 14 of this series describes the current status of some of these so-called digital biomarkers.

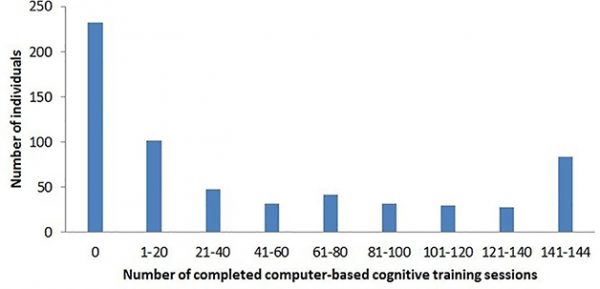

Failure to Launch. More than one-third of FINGER participants completed none of the trial’s screen-based cognitive training sessions. Lack of experience with computers was the main reason. [Courtesy of Turunen et al., 2019, PLoS One.]

Cognitive training by way of computer games is increasingly accepted as part of a dementia-prevention lifestyle (May 2019 news). At AAIC, Alina Solomon, University of Eastern Finland, reported on the experience to date from the use of computerized cognitive training in the Finnish Geriatric Intervention Study to Prevent Cognitive Impairment and Disability. FINGER enrolled 1,260 healthy people aged 60–77, who were at risk for dementia, and offered them a multifaceted, two-year intervention of exercise classes, diet plans, computer work, and social activity, plus management of metabolic and vascular risk factors. The control group got standard health advice. This intervention boosted cognitive scores (Nov 2015 conference coverage; Ngandu et al., 2015) and is now expanding to other countries as Worldwide FINGERS (Aug 2017 conference news).

This summer, the researchers published data on adherence to FINGER’s at-home cognitive training regimen aimed at boosting mental speed, memory, and executive function (Turunen et al., 2019). The results were discouraging. Of the 631 participants—a self-selected, presumably motivated group of elders—37 percent did no training at all. Only 20 percent of participants completed at least half of the possible 144 sessions; 12 percent completed all. A dose-response analysis suggested that the benefit of cognitive training increased with the number of sessions, then leveled off after 40–50 sessions, Solomon said. A minority of participants hit this mark.

The primary factor associated with starting cognitive training, and with completing more sessions, was familiarity with a computer. People who did not use a computer before were unlikely to start the training as part of FINGER.

Fortunately, the problem of poor computer literacy appears to be solving itself. Compared with when recruitment for FINGER began in 2009, the researchers now see more familiarity and use of technology in elders joining the study. “Age 60-plus 10 years ago is not the same as 60-plus now,” Solomon said. Her impression is borne out by statistics. In Finland today, 60 percent of people between 64 and 75 own a smartphone, whereas in 2011 only 10 percent did. More than a quarter of people over 75 have a smartphone. Solomon said her group is currently surveying tech use in people older than 85.

For computerized cognitive training, a person’s stage of disease matters, Solomon said. FINGER targeted at-risk elders in the general population, but scientists are now piloting a similar intervention in prodromal Alzheimer’s. In this program, 120 people are receiving regular care, the FINGER intervention, or FINGER plus a medical food. Solomon said these participants are easily stressed, so the researchers simplified training tasks, made the sessions fewer and shorter, and added social support. Participants needed more time to get acquainted with the program and to understand the difference between cognitive training and cognitive testing. Many were worried they’d forget to do the training at home. Now, the participants take the training as a group, each with his or her own laptop, before exercise sessions at the gym. So far, adherence is higher than in FINGER, Solomon said.

The move toward computerized cognitive tests to diagnose and track Alzheimer’s started on terminals in clinics, then moved to tablets, and is now bursting out of the clinic setting entirely (see 2012 news series). Jason Hassenstab, Washington University, St. Louis, pioneered the use of smartphones to measure cognition. His Ambulatory Research in Cognition (ARC) app transforms testing from quarterly, hour-long clinic sessions into frequent, brief bouts that participants perform on their personal cell phones in the course of their daily lives (Aug 2018 conference news; Dec 2017 conference news). ARC is being used in prevention trials run by the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer’s Network (DIAN) (Aug 2019 conference news). For those trials, the app enables the researchers to collect data from participants who hail from all over the world and who are younger, working and raising children, and hence unwilling or unable to travel to a clinic frequently, Hassenstab said.

At AAIC, Hassenstab shared some lessons learned from this work. He told the audience that developing a smartphone measure of cognition that could be used in a clinical trial had been arduous and costly. “Smartphone apps are a commitment, and a lot of work,” he said. Regulatory issues and documentation requirements are extensive, complex, and indeed became overwhelming. Hassenstab hired a consultant, and recommended that his fellow app developers consider early audits by such experts. To ensure privacy, ethics committees and IRBs require strict encryption and data-protection practices. Collecting data via phone cameras, and recording eye tracking or swiping behavior, are highly scrutinized. That became even more true after 2018, when the European Union implemented its general data-protection regulation (GDPR). All this makes development expensive. Hassenstab said that developing ARC for use in a trial cost $1 million.

Once deployed, the biggest challenge Hassenstab ran into was compliance. “How do we get people to do this, and to keep doing it over time?” he asked. The problem is not unique to Alzheimer’s. Adherence to electronic reporting is terrible across the board. Trials for Parkinson’s disease, asthma, and arthritis all suffer from attrition rates of 80 to 90 percent after several months, Hassenstab said.

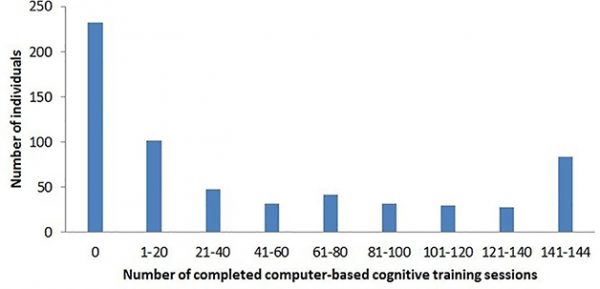

Motivational Moves. To encourage people to stick with ARC testing, WashU researchers help participants track their progress (left), and pay them (right). [Courtesy of Jason Hassenstab.]

In DIAN, 95 percent of participants will take the tests on the app once, 50 percent do it twice, and down it goes from there. What to do? Hassenstab held tutorials to help participants learn the app. After that, feedback tends to keep people engaged. To that end, ARC tracks and shows participants their progress in the overall scheme of the study. Gamification uses elements taken from computer games—think confetti and badges—to boost engagement.

DIAN scientists are also testing money as an incentive, offering 50 cents per test, plus bonuses for streaks and overall completion rates. They nudge users with reminders that invoke altruism (“We are one step closer to solving AD”) or competition (“Seventy-five percent of people have completed this—how about you?”). Hassenstab’s team is starting to collect data on how well the different techniques work.

Hassenstab offered advice for others aiming to develop a smartphone app for cognitive testing. Trying to replicate a paper test on the smartphone is difficult in practice. Simple tests work best. These rely on uncomplicated visual stimuli, animation, and easy response selection. For older people, swiping and scrolling can be challenging; games should not require a stylus. Vocal responses are possible, as is using the camera for eye tracking, but these technologies are nascent and costlier to develop.

Once a test is developed, professional beta testers can help validate psychometrics, accessibility and engagement. Hassenstab collected feedback from 1,000 users in two weeks this way, which allowed him to optimize the ARC app and deploy it on iPhones and android phones.

From the start, Hassenstab advocated a bring-your-own-device model, where people use the app on their own phones. This, too, is easier said than done. To date, 19,000 different smartphone models circulate worldwide. They differ in tap sensitivity and other parameters. If an ARC test depends on response time, the variability between phones in their respective lag between tap and recording can render results uninterpretable. After much effort building phone-tapping robots to measure lag times and standardize test results across devices, Hassenstab is now de-emphasizing response time in his data collection, instead emphasizing correct responses. The alternative—having the study provide a dedicated device—cuts development cost, eases validation, and boosts privacy. Alas, some people tend to dislike carrying two phones, and symptomatic participants in particular struggle to learn a new device and remember to keep two phones charged.

Could phone apps be used to screen for preclinical AD in the general population? That is the goal of the GameChanger project, a collaboration between the lab of Chris Hinds at the University of Oxford and partners at Roche and Eli Lilly. It tests whether the app Mezurio can detect subjective cognitive impairment and presymptomatic AD. Intended to be freely available, Mezurio contains three game-like tasks designed to measure cognitive processes that are among the first to change in AD: a paired-association learning, an executive function, and a speech-production task. The tests require five minutes per day for 30 days.

In LA, Claire Lancaster in Hinds’ group presented an update on Mezurio. Since the app’s launch in 2018, more than 16,500 people across the U.K. have used it and contributed data to the study. Users range from 18 to 92 years old, 77 percent are women, and 42 percent have a family history of dementia. They are motivated; 95 percent reported a willingness to take part in future digital health research related to dementia. To promote adherence, the researchers built reminders and encouragement, daily facts about AD research, and periodic emails into the app. And users responded: Among the first 10,000 participants, more than 3,000 completed all 30 days of testing, and most rated the experience as enjoyable. The results suggest that it is feasible to use Mezurio in the general population, Lancaster said.

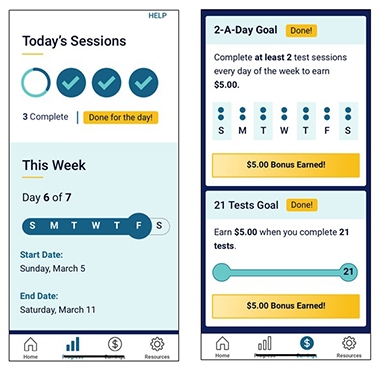

Swipe Left. In Mezurio’s GalleryGame association task, participants learn to pair swiping in a particular direction with pictures of familiar objects, and are asked to remember the pairing for up to 13 days. [Courtesy of Claire Lancaster.]

What were the initial results on detecting subjective cognitive decline? Besides its gaming features, Mezurio prompts users to self-report on their mood, sleep, and other parameters. It also collects information about “cognitive slips” on six behaviors known to discriminate preclinical AD from normal age-related cognitive change: forgetting names of familiar people or objects, word-finding difficulties, spatial disorientation, losing one’s train of thought, temporal disorientation, or trouble following a conversation or simple instructions. Every day for eight days, the app queries users to say how often they had such slips in the past six months and the past 24 hours. These queries are more specific than existing measures of subjective cognitive decline, which ask whether people or their caregivers perceive a change in memory in the last years or months that affect daily function and worry them.

At AAIC, Lancaster reported that, among the first 10,000 users, the frequency of these six types of slips in the previous six months correlated with scores on a traditional subjective cognitive complaints index. In these users, age and family history significantly predicted subjective cognition changes and frequency of slips in the past six months. Now, the scientists are looking at whether frequency of slips in the previous six months or the past 24 hours are better at predicting cognitive change when people are followed up at 12 or 24 months.

Additional cognitive test data on these 10,000 people will be presented in the coming months, Lancaster said. Besides following up with longitudinal data, she is forming collaborations with existing U.K.-based AD cohorts to compare performance on the app with medical records, genetics, and standardized neuropsychiatric testing scores.

The scientists are validating the Mezurio tests in pilot groups of older people at risk for AD by comparing them with traditional cognitive measures. The Gallery Game deployed on the Mezurio app is similar to lab-based delayed-recall tests, but assesses much longer recall intervals than possible in the lab, from one to 13 days. In one task, participants memorize the association between a photo of a real-life object and a swipe direction. A recognition task asks if the user has seen the object before. Among a test population of 36 cognitively normal people, Lancaster found significant forgetting occurred starting after three days for the association test, and five days for the recognition test, validating the use of extended testing periods. Outcomes correlated with established memory tests, according to a manuscript of the study posted on bioRχiv.

Picture This. A smartphone app from the Boston Remote Assessment of Neurocognitive Health (BRANCH) study at Brigham and Women’s Hospital uses real-life examples for at-home cognitive testing. [Courtesy of Kate Papp.]

For her part, Kate Papp of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, described how her group is exploring at-home testing in the Harvard Aging Brain Study. Previously, they had developed the computerized cognitive composite (C3) to assess subtle cognitive decline in the A4 prevention trial of the anti-Aβ antibody solanezumab. Done on an iPad using modified Cogstate software, C3 includes the Cogstate brief battery, plus two other tests of recognition and recall. One asks participants to memorize face-name associations; the other measures their ability to recall differences between similar but distinct objects, such as pairs of socks in various colors. The test comes in six different versions, which vary the test items. This allows the investigators to control for practice effects, where people test better if they see the same face-name pairs or objects over and over.

In A4, C3 serves as a secondary outcome, but participants take the test every three months in the lab. Papp wants to transition C3 to the home so she can collect data more frequently. In a pilot study, Papp gave iPads to 22 amyloid-positive and 58 amyloid-negative HABS participants to complete C3 twice a month at home. Both amyloid-positive and -negative participants performed the same at baseline, and if they repeated the same version of the test each month, everybody improved. However, amyloid-positive people improved more slowly than did amyloid-negative people. This difference emerged after four months. If the participants did a different version of the C3 each month, the learning effects disappeared, and both amyloid-positive and -negative people performed the same.

Like Hassenstab and Lancaster, Papp, too, wants to move cognitive testing to smartphones to allow even more frequent assessments on personal devices in this preclinical population. She is co-developing a new app designed like the C3 to detect subtle changes in AD-specific cognitive processes, and distinguish them from normal aging. Papp’s app draws on everyday experiences: recognizing street signs, judging prices of vegetables and, of course, face-name pairs. This app is currently being piloted in volunteers.—Pat McCaffrey

News Citations

- Smart Homes Open Doors to Insights into Aging, Dementia

- WHO Weighs in With Guidelines for Preventing Dementia

- Health Interventions Boost Cognition—But Do They Delay Dementia?

- New Dementia Trials to Test Lifestyle Interventions

- Weeklong Chinese Challenge Reveals Subtle Memory Problems

- Cognitive Testing Is Getting Faster and Better

- As DIAN Wraps Up Anti-Aβ Drug Arms, it Sprouts Tau, Primary Prevention Arms

Series Citations

Therapeutics Citations

Paper Citations

- Ngandu T, Lehtisalo J, Solomon A, Levälahti E, Ahtiluoto S, Antikainen R, Bäckman L, Hänninen T, Jula A, Laatikainen T, Lindström J, Mangialasche F, Paajanen T, Pajala S, Peltonen M, Rauramaa R, Stigsdotter-Neely A, Strandberg T, Tuomilehto J, Soininen H, Kivipelto M. A 2 year multidomain intervention of diet, exercise, cognitive training, and vascular risk monitoring versus control to prevent cognitive decline in at-risk elderly people (FINGER): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015 Jun 6;385(9984):2255-63. Epub 2015 Mar 12 PubMed.

- Turunen M, Hokkanen L, Bäckman L, Stigsdotter-Neely A, Hänninen T, Paajanen T, Soininen H, Kivipelto M, Ngandu T. Computer-based cognitive training for older adults: Determinants of adherence. PLoS One. 2019;14(7):e0219541. Epub 2019 Jul 10 PubMed.

External Citations

No Available Further Reading