Perhaps the night sky has been saved.

SpaceX, the private rocket company founded by Elon Musk, announced changes last week to a constellation of tens of thousands of internet satellites it plans to send to orbit. The alterations could prevent these false stars from polluting our views of the heavens and interfering with the science of astronomy — though issues remain for scientists to contend with.

When SpaceX launched the first batch of its Starlink orbiters one year ago, it caused an outcry among astronomers. Each satellite reflects light from the sun down to Earth — making them bright enough to give the sky a massive face-lift, particularly if the company receives permission to send forth as many as 42,000 of them to provide high-speed connectivity to customers all over the world.

As SpaceX has launched hundreds of satellites over the past year, its engineers have worked with two groups of astronomers to darken the satellites. Although scientists cannot yet say whether these methods will be fully effective, they remain hopeful that this will make them invisible to the naked eye and greatly reduce their impacts on astronomical observatories.

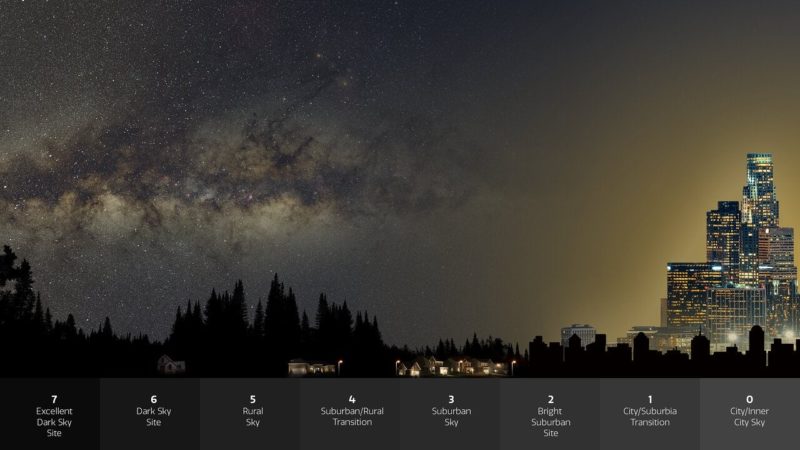

“It would have been a fundamental change to our human experience of the night,” said Tyler Nordgren, an astronomer and night sky advocate. “That bullet may have been dodged.”

The first effort to dim the satellites came in early January, when SpaceX launched one with an experimental coating meant to darken the orbiter’s reflectivity. Nicknamed DarkSat, the satellite was indeed darker — but only slightly.

Now, SpaceX will tweak the orientation of the satellites as they fly toward higher orbits. By making the solar panels edge-on relative to Earth, each orbiter will reflect much less sunlight back toward the ground after their initial deployment, when they are brightest. Additionally, they will deploy a shield — similar to a patio umbrella or a car sun visor — which will block the light from hitting the highly reflective antennas in the first place.

Patrick Seitzer, a professor of astronomy emeritus at the University of Michigan who has been running analyses of the satellites, is hopeful that the changes will make them invisible to the naked eye. That is a huge relief to astronomers and night sky advocates who initially worried that the moving lights of the orbiters would make it difficult to pick out constellations.

The changes also address a concern about the future of advanced astronomical research. When Starlink initially began, astronomers worried that the satellites would interfere with the view of the Vera C. Rubin Observatory, an American telescope in Chile that will scan the entire sky every three nights when it begins fully operating in 2023.

At that pace, scientists will build a movie of the cosmos and hunt for anything that goes bump in the night — from near-Earth asteroids to exploding stars and much more. That information will then get sent along to every major ground- and space-based observatory — alerting the entire astronomical community to new discoveries within 60 seconds so that they can follow-up as rapidly as possible.

Any threat to the Rubin observatory will therefore ripple throughout the entire field, and Starlink might have created such interference. Whenever a satellite photo-bombs an exposure, it causes a streak of light. And if that satellite is sufficiently bright, it can create ghost imprints elsewhere because of effects on the telescope’s detector.

To bypass those ghost images, Anthony Tyson, a physicist at the University of California, Davis, and the chief scientist of the Rubin Observatory, and his colleagues have built an extensive algorithm. But it only works for faint satellites. With SpaceX’s newest plans, he is cautiously optimistic that interference from Starlink satellites will become ghosts of the past.

But the satellite streaks won’t disappear from view. And as more and more launch, they will crowd the skies during the hours surrounding twilight and dawn.

“That’s a prescription for disaster,” Dr. Tyson said, because that is precisely when astronomers search for Earth-threatening asteroids.

The Rubin Observatory will also study the universe’s mysterious dark matter and dark energy. Both can be surveyed when invisible clouds of dark matter act to distort background objects, creating strange rings, arcs of light and magnified images. But those signatures look eerily similar to the artifacts created when scientists imperfectly remove satellites from their images, making it hard to distinguish between the two.

Over the next year, scientists will further simulate these effects and see if they can somehow solve the issue. In some cases, they might have to throw away Starlink images — “a worst-case scenario,” said Dr. Tyson, because of the missed discoveries and the science lost.

But many see the latest changes as a step in the right direction.

“The really good news is how cooperative and how aggressive SpaceX has been in trying to fix this problem,” Dr. Seitzer said. “It should be the standard for all future spacecraft construction.”

The problem is that there are no regulations that control how bright or dim a satellite needs to be.

“It’s the Wild West in optical astronomy,” said Joel Parriott, the deputy executive officer and director of public policy at the American Astronomical Society.

And that has caused many to fret about other satellite operators that plan to crowd the skies. To date, the British company OneWeb has launched 74 satellites, but it was slow to engage the radio astronomers who may have been affected by its proposed constellation. Although OneWeb filed for bankruptcy in March and its future remains uncertain, other companies — including Amazon, Telesat and Samsung — could soon launch their own constellations.

“There’s no guarantee that these other companies are going to behave the same,” as SpaceX, Dr. Parriott said.

But Dr. Tyson is hopeful that this example can only help.

“The fact that SpaceX has taken an attitude that they want to solve the problem sets a moral high ground for other operators to follow,” he said.

Never miss an eclipse, a meteor shower, a rocket launch or any other astronomical and space event that’s out of this world.