The skies are growing crowded.

On Friday from a spaceport in Kazakhstan, OneWeb, a telecommunications company with its headquarters in London, launched 34 satellites into space. After a few hours in orbit, the satellites will be steadily deployed and begin to build the company’s constellation, which will ultimately include 650 operational satellites — enough to provide high-speed broadband internet to every corner of the globe by the end of 2021, it hopes.

You can follow the mission’s progress in the embedded video player below:

The prospect has raised alarms for many astronomers, in part because it is the latest launch in a deluge. Since last spring, SpaceX, the rocket maker founded by Elon Musk, has launched 240 satellites, and has sought approval to deploy as many as 42,000 for its own space-based internet system, Starlink. Other companies, including Amazon, Facebook and Telesat, are also eyeing the heavens.

If OneWeb and Starlink succeed, the next decade will see nearly five times as many satellites put into orbit as all satellites launched since Sputnik 1 in 1957.

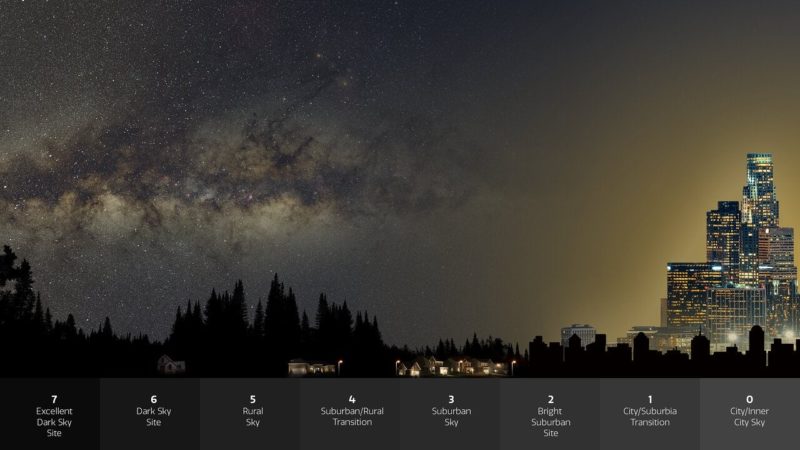

These constellations will affect astronomy research — disrupting radio frequencies used for deep space observation and leaving bright streaks in telescope images. Astronomers have had a hard time assessing the potential damage to their field, and so far much of their work has focused on Starlink. But OneWeb raises an additional set of worries.

One of the main concerns is that OneWeb’s constellation might produce radio chatter.

Astronomers have long built large radio dishes to study objects that give off little visible light but emit naturally occurring radio waves, such as distant planets, gas clouds and galaxies. Last year, radio astronomers even captured the first image of a black hole. And Earth scientists use these frequencies to measure weather.

While federal regulations protect certain radio frequencies for such research, OneWeb and SpaceX both plan to transmit signals near one of those protected bands. For astronomers, that’s a little too close for comfort.

“It’s very similar to when you have two apartments next to each other,” said Jordan Gerth, a meteorologist at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. “To some extent, the sound in one unit is confined, but if it gets too loud, it bleeds over.”

The Federal Communications Commission has required SpaceX and OneWeb to coordinate with radio astronomers. Both companies have been working with the National Radio Astronomy Observatory (N.R.A.O.), a federally funded research center, as well as the National Science Foundation.

Although each company agreed to forgo the use of the lower part of their allocated spectrum in order to avoid contaminating the protected band, SpaceX moved more quickly to make changes and sign the final operating agreement. But representatives for N.R.A.O. said that they did not hear from OneWeb for more than two years, although the company was working with the F.C.C.’s counterpart in Europe.

“It seemed to me that they were neglecting their responsibility back here,” said Harvey Liszt, N.R.A.O.’s spectrum manager.

Dr. Liszt filed a comment with the F.C.C. in 2019, and OneWeb returned to negotiations. But the company has not signed a formal operating agreement.

That’s particularly worrisome for Tony Beasley, the director of N.R.A.O., who said that OneWeb’s impact on radio astronomy could be larger than SpaceX’s. The beams sent back to Earth by SpaceX’s satellites are a little less than 30 miles wide, as the company plans to use many satellites to achieve global coverage.

But because OneWeb will use fewer satellites (and because of design differences), its beams are much larger, roughly 700 miles across at their widest. That limits the company’s ability to briefly switch off satellites while passing over locations with radio astronomy facilities, because customers would lose service, too.

While radio astronomers are figuring out the impact of satellite constellations on their work, optical astronomers are already tracking satellite streaks in their fields of view.

In mid-November, Cliff Johnson, an astronomer at Northwestern University, was monitoring the Chilean night skies when he saw a train of 60 bright points. It was SpaceX’s second batch of satellites, launched days earlier.

“It was just incredible — watching one after the other after the other,” Dr. Johnson said.

At the time, he was using the Blanco 4-meter telescope at the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory to observe the outer edges of the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds — two dwarf galaxies. Dr. Johnson suspected that when the satellites passed in front of the telescope, he might capture one or two of them. Instead, he counted 19. And SpaceX has since sent 120 more of the satellites into orbit.

“If you have tens of thousands of satellites in orbit, that’s the sort of image you would expect to have very, very frequently,” said Patrick Seitzer, a professor emeritus of astronomy at the University of Michigan.

The growing constellations could pose a serious problem to the Vera C. Rubin Observatory (formerly known as the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope) — a 27-foot telescope under construction in Chile that will scan the entire sky every three days. Because the telescope has such a wide field of view, it will more easily pick up the new satellites and could lose significant amounts of observing time, particularly near dusk and dawn.

On the surface, OneWeb’s satellites might appear to pose a smaller problem than Starlink’s.

First, there will be fewer orbiters in OneWeb’s constellation. They also orbit at a much greater distance from Earth. And they are designed to be smaller with a rough surface that reflects less light. Those three characteristics make the satellites fainter than Starlink’s, and invisible to the naked eye. That means the satellites won’t obscure your view of the cosmos during a camping trip, as so many feared when Starlink was first deployed.

But any telescope will be able to see them. In addition, their higher orbit poses a distinct challenge for large research telescopes like the Rubin Observatory.

Satellites like Starlink and OneWeb are visible only because they reflect sunlight. Once they pass into Earth’s shadow, they virtually disappear. Given that Earth’s shadow is shaped like a cone, satellites that orbit lower will be invisible for most of the night, whereas satellites that orbit higher will be visible longer.

Dr. Seitzer has found in his research that because of their higher orbits, OneWeb will be visible for two additional hours every winter evening. During the summer, they will be visible throughout the night.

Their higher orbit, will also make them appear to move more slowly through images captured by telescopes. That means that even though they’re fainter, OneWeb’s satellites could still leave a bright streak.

“It’s like if you pass your hand really quickly over a candle flame, it doesn’t hurt,” said Jeffrey Hall, the director of Lowell Observatory. “But if you pass it more slowly through, then you feel the heat big time.”

Astronomers have expressed these concerns with SpaceX and OneWeb via a small committee formed by the American Astronomical Society. While SpaceX has been receptive and launched a prototype that is partly painted black to study reductions in reflectiveness, OneWeb has only recently joined the conversation.

Ruth Pritchard-Kelly, the vice president of regulatory affairs at OneWeb said the company was committed to working with astronomers.

“It’s like the open sea — it belongs to everybody,” Ms. Pritchard-Kelly said, referring to low-earth orbit. “Making sure that anybody could connect to the internet anywhere on Earth — whether on land, at sea or in the sky — is a pretty nice vision. But so is looking into the stars — literally and metaphorically.”

Never miss an eclipse, a meteor shower, a rocket launch or any other astronomical and space event that’s out of this world.