Nature: the next big thing in climate adaptation technology? – Marketplace APM

This week, we’re revisiting several stories on how technology can help us adapt to climate change as part of our series “How We Survive.” This piece was originally published on July 18, 2019.

The term infrastructure might conjure roads, pipes and walls — pretty much the antithesis of nature. But some scientists and engineers want to reverse that impression by harnessing nature as infrastructure. The idea that plants and soil can prevent flooding and purify water is gaining traction in an era of rising seas and severe storms.

People have built levees — artificial walls and embankments — to protect cities from flooding for thousands of years. But the long history of these traditional levees is riddled with failures that are sometimes catastrophic, like the breaches that flooded New Orleans in Hurricane Katrina.

The climate crisis is only making matters worse. Growing storm surges batter coastlines, while pounding rains drench the heartland. These events call into question the reliability of traditional levees, a form of “hard infrastructure.”

One solution? Go green — as in green infrastructure.

It’s time we “start to think of our natural systems as this incredibly valuable technology,” according to Letitia Grenier, a conservation biologist who directs the Resilient Landscapes Program at the nonprofit San Francisco Estuary Institute. She said vegetation can be a better flood barrier than hard infrastructure.

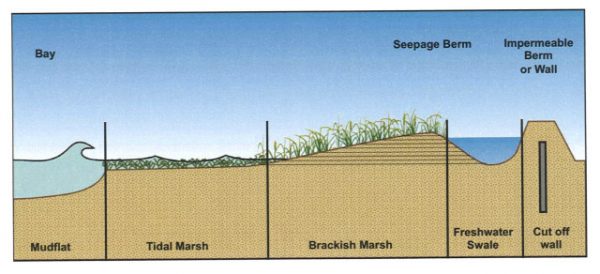

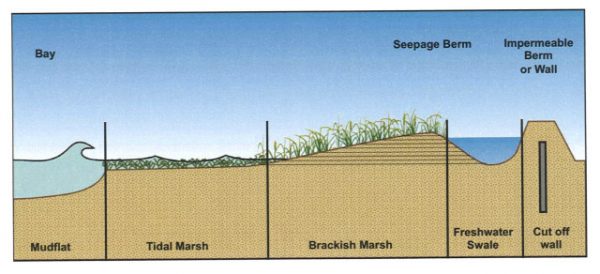

That idea is being put to the test at the Oro Loma wastewater treatment plant along the San Francisco Bay, about a 30-minute drive south of Oakland. There, rising from the sea, is a gently sloped wetland, not a wall. The two-acre marsh — or horizontal levee — is engineered to absorb the water and impact of intense storm surges. It has other benefits, too.

The horizontal levee also filters the treated waste from the Oro Loma plant perched directly above the marsh. For example, trace amounts of medicine can end up in that waste, even after treatment. But the marsh’s plants and soil help remove those drugs before they affect marine life.

The trees growing in the marsh also house rare birds. Due to the loss of their habitat elsewhere, the tidal marsh song sparrow is “found nowhere else in the world, except right here,” Grenier said. These special sparrows join others — wrens, blackbirds and more — in a daily chorus. “There’s a ton of bird song,” she said.

But building a marsh can be expensive. It requires designing the landscape, hauling in soil and seeding the plants — not to mention all the land it gobbles up. In some parts of the San Francisco Bay, engineered wetlands could cost up to $25 million per mile of coastline protected, according to geomorphologist Jeremy Lowe of the Estuary Institute. “These are not things to be undertaken lightly,” he said.

Grenier added that horizontal levees are not ideal for every coastline. The investment in constructing a marsh only makes sense where there’s something valuable to protect — like a wastewater treatment plant. Plus, she says the marsh works best to chop down storm surges in parts of the bay that typically see relatively calm surf.

But in the right setting, building a vegetated marsh can be a winning investment. That’s because natural systems are resilient — the marsh can stand up to disasters like earthquakes better than a concrete wall, said Grenier.

Grenier thinks of it as a different form of technology that could gain more ground if more people thought of it that way, too. “We have the idea of high tech, we really understand what that is,” she said. “We also have landscape tech. We have these complex natural systems that are doing really important things, and we need to take advantage of them and not think of that as something different and weird, but … just a new kind of tech … to adapt to climate change.”

In addition to flood resistance, the levee is also helping to clean the wastewater — surprisingly well, in fact.

Angela Perantoni is a researcher at University of California, Berkeley. She’s studying how well the plants on the horizontal levee are able to filter the wastewater. “Naturally, medicines pass through people’s bodies and end up in wastewater,” she said. “… It can be really hard to deal with those compounds when they end up in the environment … but in our system, everything seems to be transformed in some way.”

And the levee, with its wildlife-filled marsh, is even a crowd pleaser. Jason Warner is general manager of the Oro Loma Sanitary District. When he gives tours of this levee project, he says it makes a strong case for a different approach to climate adaptation.

“When people see infrastructure as a part of their community … something that looks analogous to a park, they’re in,” he said. “We are providing a vision for people to see what sea [level] rise response might look like.”

“We’ve shown the concept works,” Lowe said. “Now we’ve got to engineer it so that it’s buildable and affordable.”

The idea of green infrastructure has been around for decades. But it’s only gained wider adoption in recent years thanks to its multiple benefits: flood protection, water purification, habitat and climate resilience.

Major green infrastructure projects are underway or up for consideration in cities like New York, Houston and beyond. These projects show that, in some cases, the best way to guard against natural disasters may be through nature itself.