NASA taps Lockheed Martin to build six more Orion crew capsules – Spaceflight Now

NASA announced Monday it will order at least six reusable Orion crew capsules from Lockheed Martin for $4.6 billion to fly astronauts to the vicinity of the moon in the 2020s, and the agency said it plans to purchase hardware for up to 12 Orion vehicles by 2030.

The Orion Production and Operations Contract, or OPOC, sets up a production line for Orion spacecraft to support NASA’s Artemis program, which aims to return astronauts to the lunar surface in 2024, a deadline set by the Trump administration earlier this year.

“This contract secures Orion production through the next decade, demonstrating NASA’s commitment to establishing a sustainable presence at the Moon to bring back new knowledge and prepare for sending astronauts to Mars,” said NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine in a statement. “Orion is a highly-capable, state-of-the-art spacecraft, designed specifically for deep space missions with astronauts, and an integral part of NASA’s infrastructure for Artemis missions and future exploration of the solar system.”

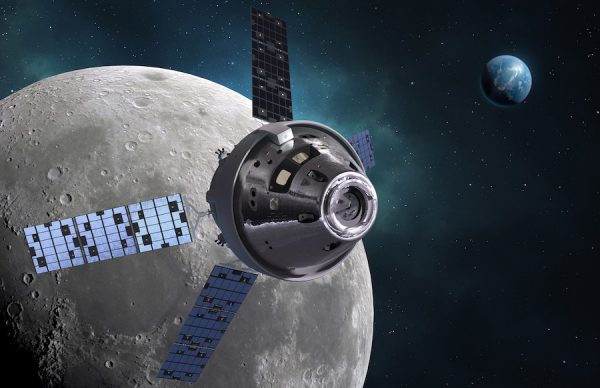

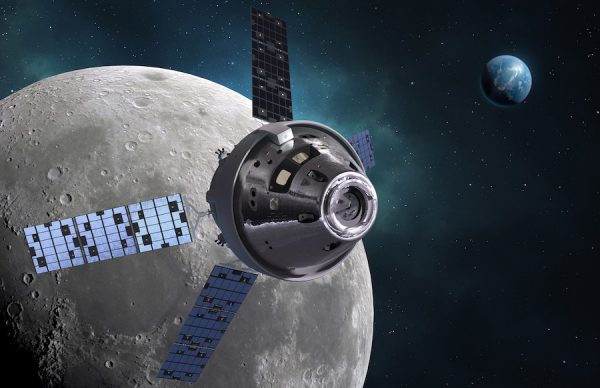

The Orion vehicles will ferry astronauts to a mini-space station, or Gateway, in orbit around the moon, where crews will transfer to a different spacecraft to take them to the lunar surface. The lander will bring the astronauts back to the Gateway once their surface missions are complete. Astronauts will leave the Gateway in their Orion spaceship and return to Earth for a splashdown at sea.

After the Artemis program’s first moon landing, NASA plans a series of follow-on missions at a rate of about one per year with expanded exploration capabilities, with the objective of demonstrating technologies and techniques for a future human expedition to Mars.

The Orion spacecraft is a centerpiece of NASA’s lunar exploration program, along with the Space Launch System, a heavy-lift rocket built by Boeing and Northrop Grumman. The SLS will boost the Orion crew capsules toward the moon.

NASA selected Lockheed Martin to develop the Orion spacecraft in 2006, when the capsule was part of the Constellation moon program launched by President George W. Bush. The Constellation program was canceled in 2010, but the Orion spacecraft survived and became part of a new deep space exploration initiative under that Obama administration that focused on a human mission to Mars.

Sometimes called the “multipurpose crew vehicle,” the Orion spacecraft and its SLS launcher have been retargeted toward the moon under the Trump administration.

Before the new agreement announced Monday, NASA had contracted Lockheed Martin to build two Orion spacecraft capable of flying to the moon. The first lunar-capable Orion spacecraft will launch on the Artemis 1 mission, an unpiloted test flight set for launch on the first flight of the Space Launch System heavy-lifter.

The Artemis 1 mission will likely be ready for launch in 2021, followed by the Artemis 2 flight in 2022 or 2023 with four astronauts on-board. Artemis 2 will launch on a trajectory that will take the Orion crew around the moon and back to Earth.

The first of the new batch of Orion crew capsules will launch on the Artemis 3 mission, which NASA has tapped to attempt the first landing on the moon by astronauts since Apollo 17 in 1972.

Mike Hawes, Lockheed Martin’s Orion program manager, said Monday that the company’s new contract with NASA will include crew modules, complete launch abort systems, and adapters to connect the Orion crew modules with their European-made service modules. The contract also covers parts of the European service modules procured by Lockheed Martin, such as auxiliary rocket engines and network interface cards, Hawes said.

The construction of the European services modules themselves is separately funded by the European Space Agency. Airbus Defense and Space is the prime contractor for the Orion service module.

Buying Orion vehicles in groups of three allows Lockheed Martin and its subcontractors to achieve production efficiencies and cost savings, he said.

“The contract is structured as what NASA calls IDIQ, indefinite delivery/indefinite quantity, so they can order as many as they see fit,” Hawes said. “Three is what were able to show NASA was a good break point in terms of being able to get good cost savings by ordering all at once.”

The first set of three Orion vehicles purchased by NASA for $2.7 billion on Monday will come with an average cost of $900 million each. NASA says it plans to order an additional three Orion vehicles in fiscal year 2022 for $1.9 billion, or $633 million per mission.

“I am pleased that Administrator Bridenstine has heeded my calls and is taking significant steps to ensure that Johnson continues to grow with the exciting future of manned exploration that lies ahead,” said Sen. Ted Cruz, R-Texas, in a statement. “More needs to be done, and I look forward to production ramping up in the weeks and months to come and to more opportunities with NASA.”

The NASA announcement of the Orion production contract included statements from Cruz and other Texas lawmakers lauding the role of the Johnson Space Center in Houston, where NASA manages the Orion program. Lockheed Martin’s Orion production line is located at the Operations and Checkout Building at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

“We will heavily reuse all of the components from flight to flight, and we will also reuse full structures, vehicles,” Hawes said. “Some things, like the crew module adapter, since it’s on the service module and gets thrown away each flight, that will be new each flight. The launch abort system, since it gets thrown away each flight, that will be new each flight. But one of the advantages that we have in that second order is we start to see the power of reuse and the price comes significantly down.”

According to NASA, internal computers and electronics, as well as crew seats and switch panels, from the Artemis 2 mission’s Orion spacecraft will be re-flown on Artemis 5. The entire Artemis 3 crew module will be reused on Artemis 6.

“We have doing qualification testing for internal components to five uses,” Hawes told Spaceflight Now in an interview. “Things like the avionics, the flight computers, the communications gear, those kinds of things we anticipate that we will be able to get five uses. The primary structure, for sure two (uses), and we’ll continue to work with NASA to demonstrate the data that we get out of our flight experience. I think we will continue to revise how much we’ll be able to use the structures. But we’re planning for two, at least.”

“That’s the theme,” he said. “Once we demonstrate the capability, then three flights later, that vehicle could fly again.”

The Orion spacecraft can accommodate up to four astronauts for standalone missions lasting up to 21 days. Missions that dock at an in-space destination, such as the Gateway, could last longer.

NASA could order hardware for as many 12 Orion missions from Lockheed Martin under the new production contract, but Hawes said that does not mean the 12 crew modules will be built.

“NASA talks about up to a total of 12 missions,” Hawes said. “That phrase is a little nuanced because with the reuse plan that we’ve the entire time we’ve been planning for this contract, we certainly will not build 12 spacecraft.”

“It’s anticipated that those (6 additional) orders will utilize the full suite of reuse capabilities,” he said. “So those missions NASA will contract with us for, and they may be characterized as light reuse, meaning the components, versus heavy reuse, meaning the structure. We expect when we get the request for proposal for those follow-on missions, that it will actually come with an assumption about what the reuse (plan) for each one of those missions is.”

NASA is ordering the first six Orion vehicles through a “cost-plus-incentive-fee” scheme, a type of contract that treats the Orion spacecraft still as a work in progress. NASA said it will negotiate “firm-fixed-price” orders for follow-on Orion missions, once the spacecraft “design stabilizes and production processes mature.”

“One of the challenges that we have is that we have this first order, we have to make it at this time to meet the Artemis 3 schedule, but we haven’t finished the design of some of the critical systems, like the full life support and the crew controls and displays,” Hawes said. “Those are the biggest pieces that get added. And then in 2022, we anticipate that second … three-mission order … but we will still have not flown Artemis 2, most likely.

“So that’s really the risk factor of those first few flights, is we just haven’t completed and demonstrated the full development task,” Hawes said. “And then from that point on, because of reuse, we see a good (cost) reduction in that second order, and then the follow-on orders will be firm-fixed-price, and we will expect to continue to see price savings.

“We’ve done lots of things in terms of the vehicle to bring price down,” Hawes said. “The bulk ordering is one of the big things that we’ve worked on. We’ve continued to work on advanced technologies, more 3D printing. We actually use augmented reality now in some of our build processes, so a lot of the things that we have been learning over the last couple of years, we’re actually fully putting into place with this new contract.”

Meanwhile, Airbus has delivered the first European service module for the Artemis 1 mission, and production of the second unit for Artemis 2 is well underway. ESA has authorized Airbus to begin procuring hardware for a third Orion service module for the Artemis 3 mission, and European officials have expressed interest in providing additional service modules well into the 2020s.

The service modules provide propulsion, propellants, electricity, water, oxygen, nitrogen and thermal control for the Orion spacecraft.

In a congressional hearing last week, a senior NASA official said the agency aims to have a similar production contract in place for the Space Launch System in about a year.

NASA has spent more than $16 billion on Orion spacecraft development since the program’s start under the George W. Bush administration. When NASA announced Lockheed Martin as the Orion prime contractor in 2006, the first Orion mission with humans on-board was planned in 2014, followed by a crewed lunar landing in 2020.

The development of the Space Launch System started in 2011. At that time, NASA said the first SLS test flight could take off by the end of 2017.

But political redirections, technical problems, poor contractor performance and NASA mismanagement have slowed advancement on the SLS and Orion programs.

In a report released in June, the Government Accountability Office wrote that “contractor performance to date (on the SLS and Orion programs) has not produced desirable program cost and schedule outcomes.” The GAO also identified “significant disconnects” between contractor performance and award fees NASA has paid to Boeing and Lockheed Martin, despite continued delays and cost growth.

The GAO has also “found that NASA has made programmatic decisions — including establishing low cost and schedule reserves, managing to aggressive schedules, and not following best practices for earned value management — that have compounded technical challenges that are expected for inherently complex and difficult large-scale acquisitions.”

“As a result, NASA overpromised what it could deliver from a cost and schedule perspective,” the GAO reported.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.