NASA plans to launch first two Gateway elements on same rocket – Spaceflight Now

Aiming to reduce risk and costs, NASA has decided to launch the first two modules of the Gateway station in lunar orbit on the same heavy-lift rocket in 2023, rather than fly them on separate rockets and dock them together in deep space, according to the the agency’s chief human spaceflight manager.

NASA has not selected a rocket to carry the two modules into space, but the massive payload could fit on a SpaceX Falcon Heavy rocket with a lengthened payload fairing currently in development to accommodate large U.S. military satellites, according to Doug Loverro, NASA’s associate administrator for human exploration and operations.

In an interview, Loverro told Spaceflight Now that launching the Gateway’s Power and Propulsion Element and the Habitation and Logistics Outpost — known as the PPE and the HALO — will save money and reduce technical risk on the program.

Agency managers previously intended to launch the PPE module and the HALO on separate rockets in 2022 and 2023.

“What we had was a Power and Propulsion Element that had its own launch on a Falcon Heavy, and we had a HALO with its own launch on a Falcon Heavy, and they were then going to have to have independent propulsion systems, and independent docking systems, and independent power and guidance and control systems,” Loverro said. “They were both going to have to independently get their way to the moon and then (autonomously) dock with each other.

“And then the complexity of routing all of the power for the long-term for the Gateway through that docking mechanism, and fluids and other things that we needed to do, all made that system quite complex,” Loverro said. “We realized that if we could put it all together on the ground, we got rid of all that risk and reduced the cost, not just because we saved a launch vehicle but because we got rid of a whole bunch of added complexity in the system.”

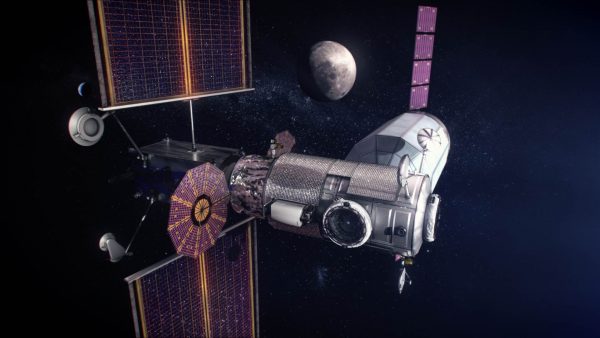

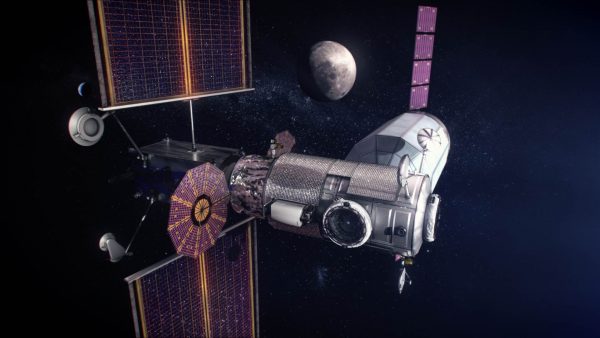

The Gateway is a mini-space station NASA plans to build in an elliptical orbit around the moon that swings as close as 1,000 miles from the lunar surface about once per week. The Gateway will act as a stopover and safe haven for astronauts heading for the moon’s surface in NASA’s Artemis lunar program.

NASA is designing the mini-station to accommodate myriad scientific experiments and engineering demonstrations required for more ambitious ventures deeper into the solar system, and eventually Mars.

Loverro said NASA originally decided to launch the two Gateway modules on different rockets because of limited volume available on existing rockets, such as SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy launcher.

“It turned out that under the Air Force proposal for their follow-on launch services, I knew of the fact that new fairings were being asked for in order to meet the DoD (Department of Defense) needs that would go ahead and meet the needs of that,” said Loverro, a veteran manager of national security space programs who joined NASA late last year. “So I asked the team to go look at that. We verified that, indeed, it worked and it fit in.”

The new plan for a single launch in 2023 buys time for engineers developing the PPE, which will be built by Maxar Technologies. Northrop Grumman is charged with developing the HALO module, which will provide limited living quarters for astronauts on the way to the moon.

The revamped Gateway architecture also makes the engineering job easier because the modules can be connected together on the ground.

The PPE will be fitted with large roll-out solar arrays to generate electricity. The propulsion system will consist of high-power solar-electric thrusters developed by Aerojet Rocketdyne.

“It took the schedule pressure off the PPE so we are now able to go ahead and integrate any changes to the PPE to make it even a better longer-term solution by changing the momentum wheels that we use for it, the power handling system, providing more access for some of the robotic arms will be used,” Loverro said. “So we were able to actually make the changes that really create a better long-term solution.

NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine approved the change.

“The goal is to increase the probability of success and minimize risk, and at the same time reduce cost,” Bridenstine told Spaceflight Now. “This was a concept that Doug looked into and determined was the right approach.”

“This is one of those incredibly rare situations in program management where you look at a problem, and you add in one new piece, and suddenly it makes the job easier, cheaper, less risky, and with better results,” Loverro said. “It was a no-brainer.”

Loverro said the PPE and HALO modules will launch on a commercial rocket.

“We will compete at the time for what launch vehicles might be available,” Loverro said. “We needed to verify that at least one would be available for it, but based upon what the Air Force is asking for under their contract, there should multiple available at the time. That will be a competition that we run some time in the near future.”

Other launchers that could carry the integrated PPE and HALO modules into space include United Launch Alliance’s Vulcan Centaur and Blue Origin’s New Glenn. But SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy is the only one of the three currently operational.

NASA envisions the Gateway as a staging area for expeditions to the lunar surface, but the Artemis program’s first moon landing mission in 2024 is not expected to utilize the Gateway, Loverro and Bridenstine said. Instead, a commercial lunar lander will launch on a commercial rocket into a similar high-altitude orbit around the moon, where an Orion crew capsule will dock with four astronauts after departing Earth aboard NASA’s heavy-lift Space Launch System vehicle.

Last week, NASA selected Blue Origin, Dynetics and SpaceX to continue working on their lunar lander concepts. The agency plans to review the three concepts in early 2021, then select one to proceed into full-scale development for the Artemis 3 mission in 2024.

The shorter-term goal set by the Trump administration for NASA’s Artemis program is to land the first woman and the next man on the moon by the end of 2024. Four years later, in 2028, NASA intends to have a “sustainable” infrastructure in place to allow regular landings on the moon with commercial and international partners, including reusable landers and longer-term stays on the lunar surface.

“The two challenges we have, one is to go fast, and one is to go sustainably,” Bridenstine said. “When we think about a sustainable presence at the moon, we absolutely need a Gateway. The Gateway gives us the ability to reuse landers, over and over again, which drives down cost and it increases access. The Gateway gives us access to different orbits around the moon, so we can get to the north pole, the south pole, the equatorial regions, and everything in between. The Gateway is also transformable. We can use it eventually for our ship to Mars.”

The Canadian Space Agency, the European Space Agency and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency plan to participate in the Gateway project, contributing a robotic arm, refueling and communications hardware, and habitation and research capacity. Those international elements will launch after the PPE and HALO are placed into lunar orbit.

“The Gateway gives us the opportunity to do science, and it gives us a lot of credibility with our international partners, who are very interested in helping us build out the Gateway,” Bridenstine said. “I just want to emphasize the Gateway, we are 100 percent committed to the Gateway.”

Dan Hartman, NASA’s Gateway program manager, said in March that the Gateway will be capable of supporting a crew of four astronauts for up to 30 days. With a pre-positioned logistics module, that mission duration could be doubled to 60 days.

NASA has contracted with SpaceX to deliver logistics to the Gateway using an extended version of its Dragon spacecraft launched by a Falcon Heavy rocket.

Despite the station’s selling points, taking the Gateway out of the critical path for a lunar landing in 2024 made sense, Bridenstine said.

“It is also true that we’re 100 percent committed to getting to the moon as fast as possible,” he said. “So anything that is not necessary, we intend to remove from that path for speed. So the first moon landing, we’re intending not to use the Gateway.

“That means that we will not have the Gateway in place for the first landing on the surface of the moon. The second time when we land humans on the moon, we absolutely want to have the Gateway in the mix because we need to land on the moon by 2024, and we need to have a sustainable presence by 2028.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.