NASA Launches ICON to Explore Earth’s Ionosphere – Sky & Telescope

The Ionospheric Connection Explorer (ICON) satellite will explore the boundary between Earth and space.

An artist’s conception of ICON in space.

NASA

A Northrop Grumman Pegasus XL rocket, ejected from the fuselage of a Stargazer L1011 aircraft, lofted an exciting new mission into low-Earth orbit last night: NASA’s Ionospheric Connection Explorer (ICON).

ICON will study the ionosphere, the region in Earth’s atmosphere that’s charged by incoming sunlight. In the ionosphere, which includes multiple layers of the uppermost atmosphere, rarefied ions (hence the name) and free electrons flow freely, affecting Earth’s magnetic field, radio communications, the orbit of low-Earth satellites, and many other aspects of Earth-space interactions.

“ICON is unique,” says Thomas Immel (Space Sciences Laboratory and University of California, Berkeley). “The mission design allows for a new investigation into how the atmosphere and ionosphere are connected.”

The mission marks the 39th successful launch and satellite deployment by a Pegasus XL rocket launching from the aircraft platform. Other L1011/Pegasus XL alumni include the NUSTAR X-ray observatory and the Interstellar Boundary Explorer (IBEX). ICON, operated by the University of California at Berkeley’s Space Sciences Laboratory, is the latest member of NASA’s Explorers program, a lineage that goes all the way back to the first successful U.S. launch of Explorer 1 on January 31, 1958.

The Long Road to Launch

Inclement weather along the Florida Space Coast delayed the launch by one day, from October 9th to October 10th. But several other delays, largely rocket-related, hindered the mission’s road to the launchpad.

ICON’s launch was originally going to occur out of the Kwajalein Atoll in the Pacific in late 2017, but this was delayed to the summer of 2018 due to problems with the Pegasus XL rocket. Another launch, this time from the Cape in October 2018, was delayed due to faults in the rocket’s avionics.

The Pegasus XL rocket with ICON mated to a fuselage pylon on the L1011 ‘Stargazer’ aircraft prior to launch. Ben Smegelsky / NASA

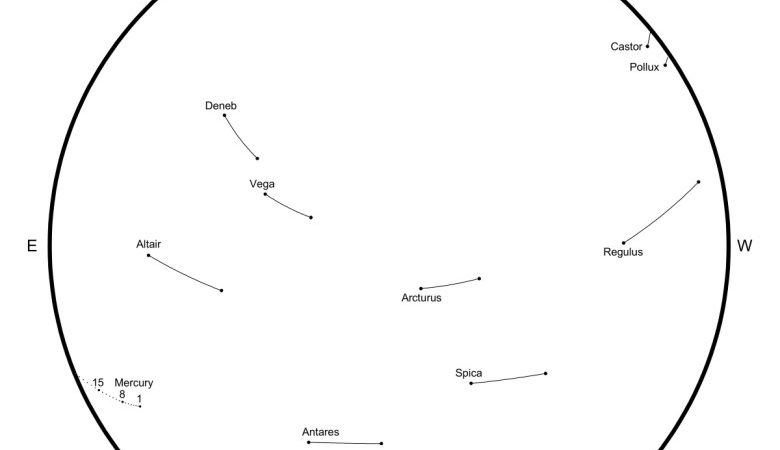

Slated for a two-year primary mission, ICON is headed for low-Earth Orbit (LEO), inclined 27° to Earth’s equator with a perigee of around 357 miles (575 kilometers). In an orbit similar to the Hubble Space Telescope, this 641-pound (291-kilogram) observatory will be visible to satellite spotters from latitudes between about 30°N (think central Florida) to 30°S. ICON is now listed in orbit as probable (see the comments after the article) NORAD ID 2019-068A.

“The inclination and orbit altitude, the pointing and detector capabilities of the instruments, all lend themselves to observing the connections between the lower and upper ionosphere,” says Immel. “In any 7-minute period we collect all the drivers and responses of the ionosphere in the region we are moving through.” ICON will pass through the magnetic equator 30 times a day, enabling it to make quick, simultaneous observations of ion velocities.

ICON undergoing testing in the lab on Earth.

NASA / UC Berkeley / ICON

The Science of ICON

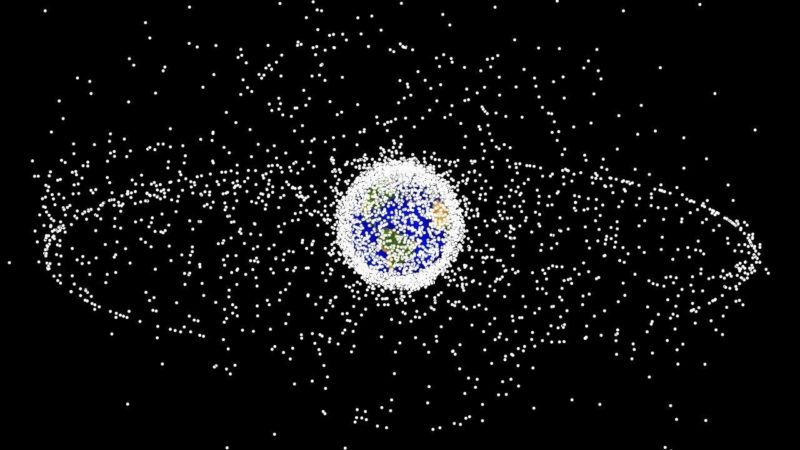

ICON will look at the interaction between the ionosphere and the tenuous thermosphere within which it’s embedded. Gases in this region of our upper atmosphere are a mix of neutral and charged particles and are move around via convection, winds, daytime heating and nighttime cooling, and solar activity. Not only do these movements affect radio and GPS communications, they also affect the drag on space debris and satellites in low-Earth orbit.

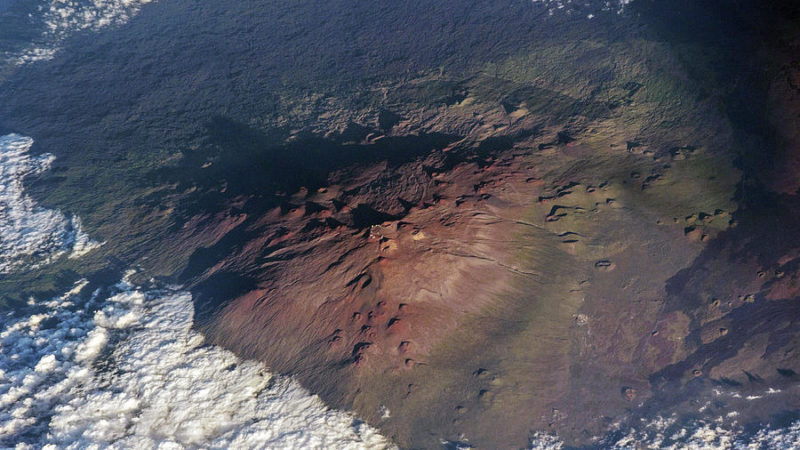

ICON will also measure and characterize airglow, caused by charged particles floating in the upper atmosphere. This phenomenon (sometimes also referred to as skyglow) is familiar to astrophotographers in search of dark skies, as it means the night sky never appears truly black. This phenomenon is also readily apparent to astronauts aboard the International Space Station, looking back at the nighttime limb of the Earth.

Airglow as seen from the ISS.

NASA

To study the interactions of particles in the upper atmosphere, ICON will use four instruments allowing for both remote and in situ observations:

- Two ultraviolet imagers built by University of California, Berkeley, which will look at airglow in the upper layers of Earth’s atmosphere.

- An ion drift meter built by the University of Texas at Dallas, which will analyze the motion of ionized particles in Earth’s ionosphere.

- A Michelson interferometer provided by the United States Naval Research Laboratory, which will document the temperatures and winds in the thermosphere.

About the size of a large refrigerator, ICON is equipped with 780-watt solar arrays to power the instruments in science mode.

Science measurements will begin at solar minimum, as we’ve come off of Solar Cycle #24 and await the start of Solar Cycle #25. “Starting at solar minimum, we should get a very good look at the terrestrial drivers of space weather before the Sun starts adding more variability,” says Immel. If all goes well ICON, initially set for a two-year mission, could last for more than a decade, taking it right through solar maximum and into the next minimum.

Understanding how space weather affects Earth’s atmosphere is crucial for our technological civilization. ICON will pave the way for understanding this complex interplay and provide insight into possible ways to ameliorate its effects on communications and society.