Moonlight challenges Leonid meteor shower maximum on 18 November – Astronomy Now Online

Every year from 5 to 30 November, Earth ploughs through debris shed from Comet 55P/Tempel-Tuttle and strewn along its orbit. Most of these cometary dust grains are smaller than a grain of rice, but they enter our atmosphere at speeds close to 250,000 kilometres per hour (~44 miles per second) and burn up due to friction with air molecules some 50 miles (80 kilometres) above the ground, leaving a brief incandescent trail that we see as a shooting star, or meteor.

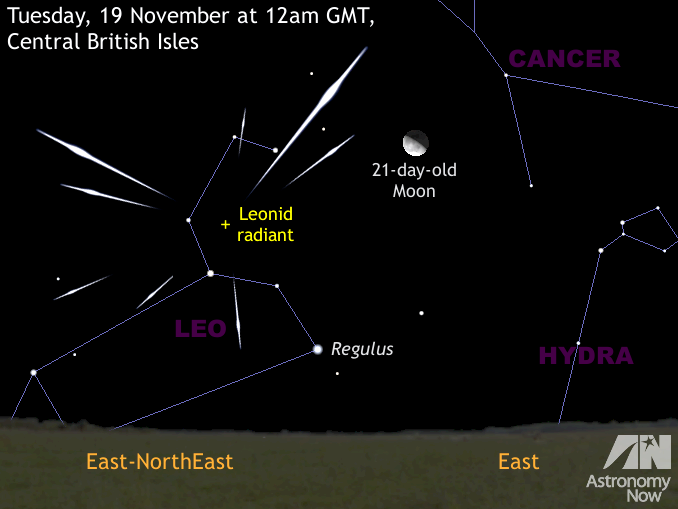

The Leonid meteor shower – so-called due to the constellation of Leo from which they appear to originate – is well known for fast meteors, the brightest leaving persistent trains that appear to hang in the air for several seconds. Spectacular shooting stars are known as fireball or bolides and are created by cometary debris that might initially have been the size of a grape.

Discovered in December 1865, Comet 55P/Tempel-Tuttle has an orbital period of 33 years and the number of meteoroids it spawns (and hence the number of shooting stars seen) grow in intensity when the comet is near perihelion, its closest approach to the Sun — though at such times we are seeing the debris from former returns that happen to be densest here rather than newly liberated material from the comet.

The Leonids can put on truly extraordinary displays, as witnessed in 1833, 1866, 1966 and 2001. Woodcut prints of the Leonid storm of 1833 depict a continuous rain of shooting stars. Contemporary accounts talk of perhaps a quarter-million meteors seen over a nine-hour period as seen from North America.

The Leonids of 2019

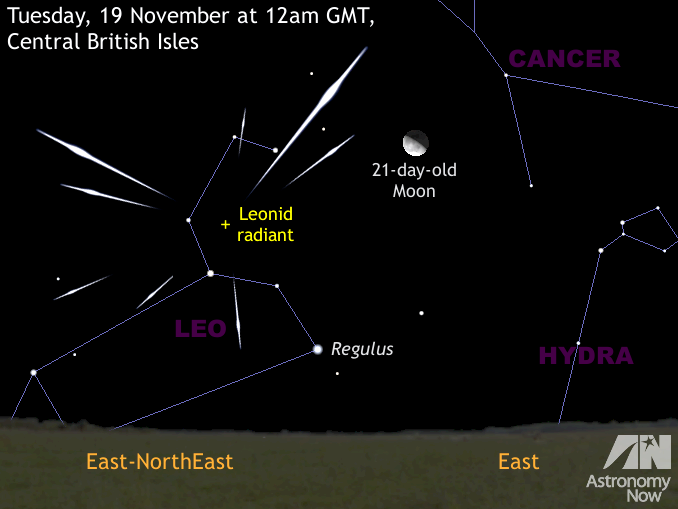

However, don’t get too excited at the prospect of seeing a spectacular display around the maximum predicted for 11pm GMT (23h UT) on Monday, 18 November 2019 for two reasons. First, Comet 55P will not return to the inner Solar System until 2031, and heightened activity is unexpected until the late 2020s. Second, the 21-day-old waning gibbous Moon lies above the UK horizon from 9:30pm GMT until dawn.

While it is probable that a Leonid meteor might otherwise be seen, on average, every four minutes near maximum from a dark sky site, the glare of the Moon just 13 degrees (or a span-and-a-half of a fist at arm’s length) to the right of the radiant – the region of the constellation of Leo from which the meteors appear to originate – is going to obliterate all but the brightest shooting stars.

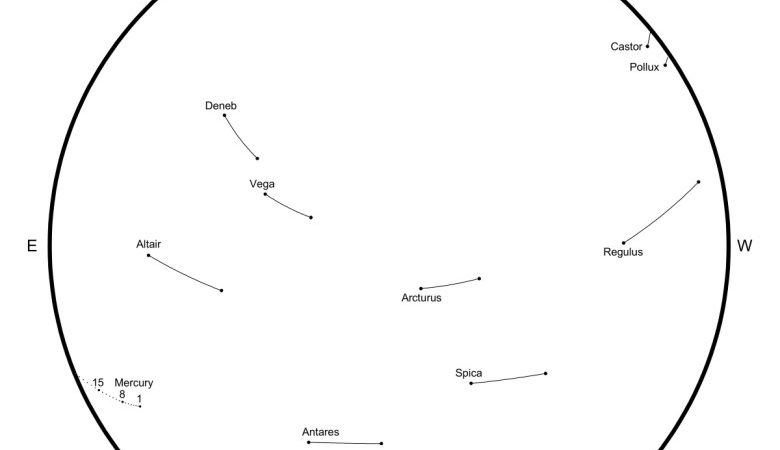

However, for those of you up for the challenge, try to find a safe place as far removed from light pollution as you can soon around midnight that offers a clear view of the eastern sky and direct your attention to the sky halfway from the horizon to overhead.