Dr. Jo-Anne Ferreira at a reading at Paper Based bookstore in Port of Spain, Trinidad. Photo courtesy Ferreira, used with permission.

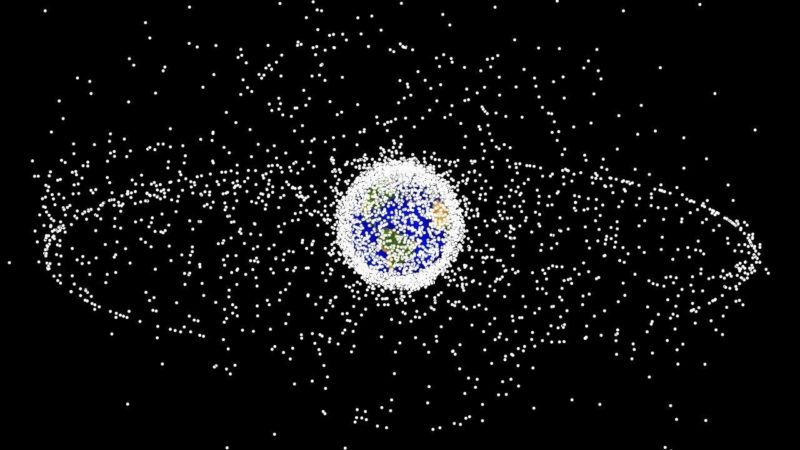

This is the second instalment of an interview with linguist Jo-Anne Ferreira, who won the Trinidad and Tobago segment of a worldwide competition aimed at finding a pair of names for an exoworld, hosted by the International Astronomical Union (IAU) in honour of its 100th anniversary.

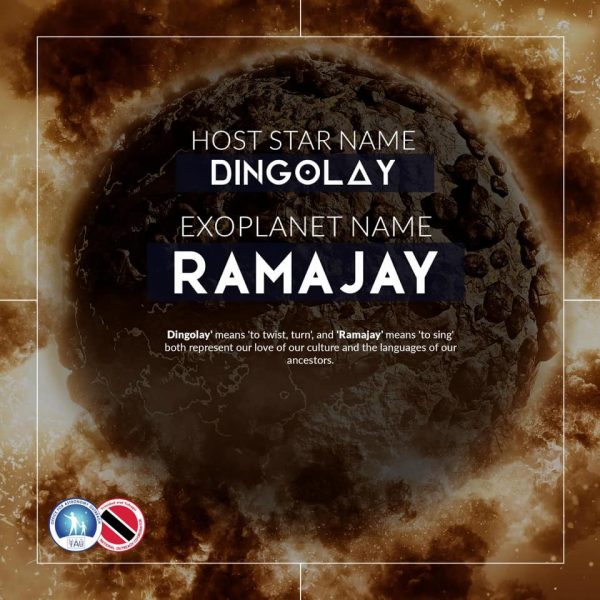

Graphic summarising the winning entry from Trinidad and Tobago in the NameExoWorlds competition. Image courtesy Jo-Anne Ferreira.

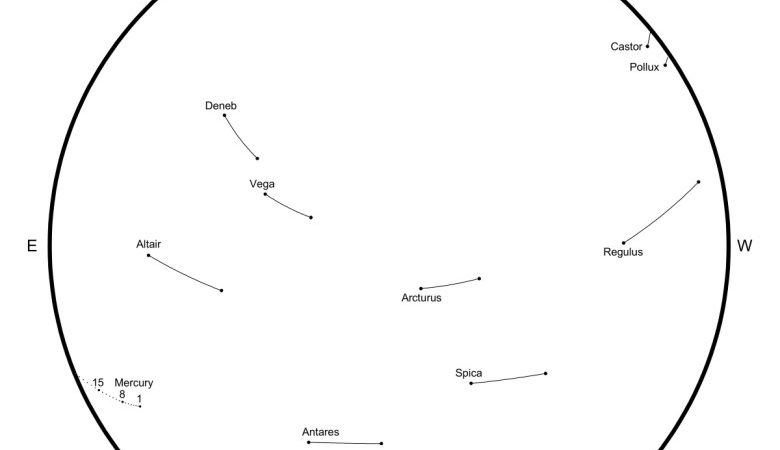

The names Ferreira put forward for the new star and its co-relating exoplanet, are Dingolay and Ramajay, the linguistic significance of which was explored in Part 1 of this series, in which Ferreira notes that the name selection was also a triumph for Patois. (If you want to stargaze and find the exoworld, Universe Guide offers detailed directions.)

As our conversation continues, Ferreira talks about the importance of language itself, and how linguistics is — in her words — “in everything … it’s like maths and physics.”

JMF: Why do you think your win was significant for Patois, and what type of resources does the language need?

JAF: Patois has been here at least since 1783, for over 235 years. The year 2019 was significant for Patois — it was the 150th anniversary of John Jacob Thomas‘ “The Practice and Theory of Creole Grammar”, republished on its 100th anniversary and available in print and on archive.org; Patois pioneer professor emeritus Lawrence D. Carrington, professor of Creole linguistics, educational research and development, won the Chaconia Medal Gold for language and development; and Patois made it to the stars — all great for a language that has had little recognition and respect.

Patois absolutely needs resources — print, digital and more. We have a language documentation project afoot, and [language teacher] Nnamdi Hodge and I trek across the country interviewing as many Patois-speaking elders as possible, and filming, transcribing, translating and archiving. We have a Facebook page and Nnamdi has a YouTube channel. We can’t do it alone though. We hope to embark on community-based language development, with “The Guide for Planning the Future of Our Language”.

Based on the work of professors Carrington and Jean Bernabé, and colleagues of CRILLASH, Université des Antilles in Martinique and the Folk Research Centre of St Lucia, we’ve also developed a project about the Patois alphabet that’s now in its pre-final version. We hope that the author, Gertrud Aub-Buscher, will finish her dictionary soon.

Image of The Patois Alphabet project, courtesy linguist Jo-Anne Ferreira, used with permission.

JMF: What is the state of Patois in Trinidad and Tobago and the wider region — and why do you always insist on capitalising the word?

JAF: Antillean or Atlantic French-lexicon Creole is alive and well in many countries of the Caribbean, and it is the Number 2 language of the region, after Spanish. Thanks to Haiti, it is also the Number 1 language of CARICOM, even with 13 English-official countries.

Patois was once spoken by every creed and race in this country. It belongs to no one and everyone. Unfortunately, it is dying in Trinidad and Tobago, Grenada and Venezuela, since it is no longer a first language.

Here, however, it is so interwoven into our everyday speech that most of us don’t even recognise that some things we say are Patois or due to Patois. We haven’t truly grasped the impact of Patois on what and how we speak: calques, vocabulary in the areas of flora, fauna, foods, folklore and festivals, music, place names, our syntax, pronunciation, and intonation. Patois itself has borrowed from many other languages in our space, sharing a symbiotic relationship with them. It’s time for a return to roots to explain the present, and to understand our uniqueness.

With 12,200 entries, Patois may constitute only 10 percent of Lise Winer’s edited “Dictionary of the English/Creole of Trinidad and Tobago”, but it’s deep in our marrow and linguistic DNA. Everyone needs to get this dictionary and get it now.

I insist on capitalising my name, my language, my nationality. We just mentioned that words change, and change they must, if they are around long enough or if they change location. Those who happen to know that a patois in France is a non-standardised regional variety of French don’t seem to know that that common noun changed and became a proper noun here, regardless of any stigma attached to the French meaning. Any negative word can undergo amelioration, because of the will of the speakers and their power to determine the course, the meaning, the status, definition and even the connotation of any word. In English, all proper nouns are capitalised. French stopped being a reference point for English a long time ago.

The spirit of Patois has triumphed in the face of adversity and it will not be put down or humiliated any longer.

JMF: You believe that linguists should be all about equality. Why?

JAF: Because no language can possibly be superior to another. We describe, not prescribe or proscribe. Why tell a silk fig that it is a bad lacatan? We are who we are. So it’s equal language rights for all. We have declarations, charters, codes, etc.

JMF: You also believe that our attitude toward language has ripple effects.

JAF: Crime is linked to lack of jobs, [which] is linked to lack of education, [which] is linked to lack of language access. Is nobody seeing the link twixt crime and language?

Language policy and language planning fall right under sociolinguistics — you can plan for people to acquire a language; legally and socially raise the status of a language, and add vocabulary by creating dictionaries and grammars. We currently have no national language policy. CARICOM and the Association of Caribbean States don’t have language policies either.

If I could get statistics of how many nationals go to university here and how many can’t, see where they came from, their home language, I think the connections would be clear. We continue to demotivate the monolingual Creole/Dialect speakers. We need to stop that.

It’s not like English is totally foreign here, but it’s like a second language for too many. I have no problem with English as our national official language — it’s part of us — but I do have a problem with the minoritising of the majority and their language. Bilingualism and multilingualism are normal around the world. The problem is we like to think of bilingualism as good only if it includes a language with status.

Lack of language access slows people down: in education, in getting the right job […] so if it’s English needed, then teach it as a skill, using students’ backgrounds as bridges — not barriers.

JMF: In a society as diverse as Trinidad and Tobago, doesn’t language have the power to connect us?

JAF: We have operated exonormatively for such a long time, but more and more, as any nation should, we are coming into our own. Individual words, like dingolay and pelau [a rice dish], belair/bèlè, [a dance], have more than one origin. All of our languages, past and present, have gone into making us who we are. One of my students is investigating linguocultural rich points, and it’s fascinating. Trinbagonians are connected through a shared linguocultural history and present — we don’t have to constantly define or explain or substitute our words in our conversations.

JMF: How do you notice Caribbean languages — indigenous and inherited — evolving?

JAF: Intangible cultural heritage is being recognised more and more. Language reclamation is happening. Long live endonormativity — we will dictate our own pace.