Light Pollution Is Dimming Our View of the Sky, and It’s Getting Worse – Scientific American

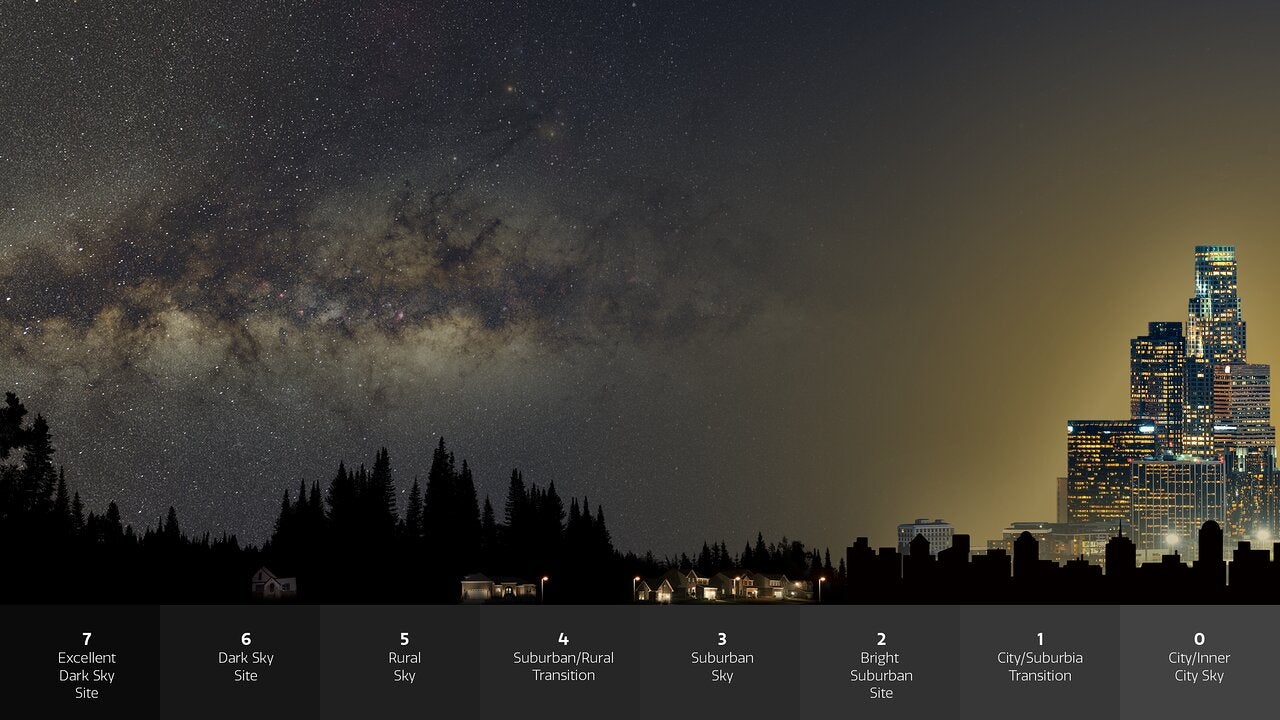

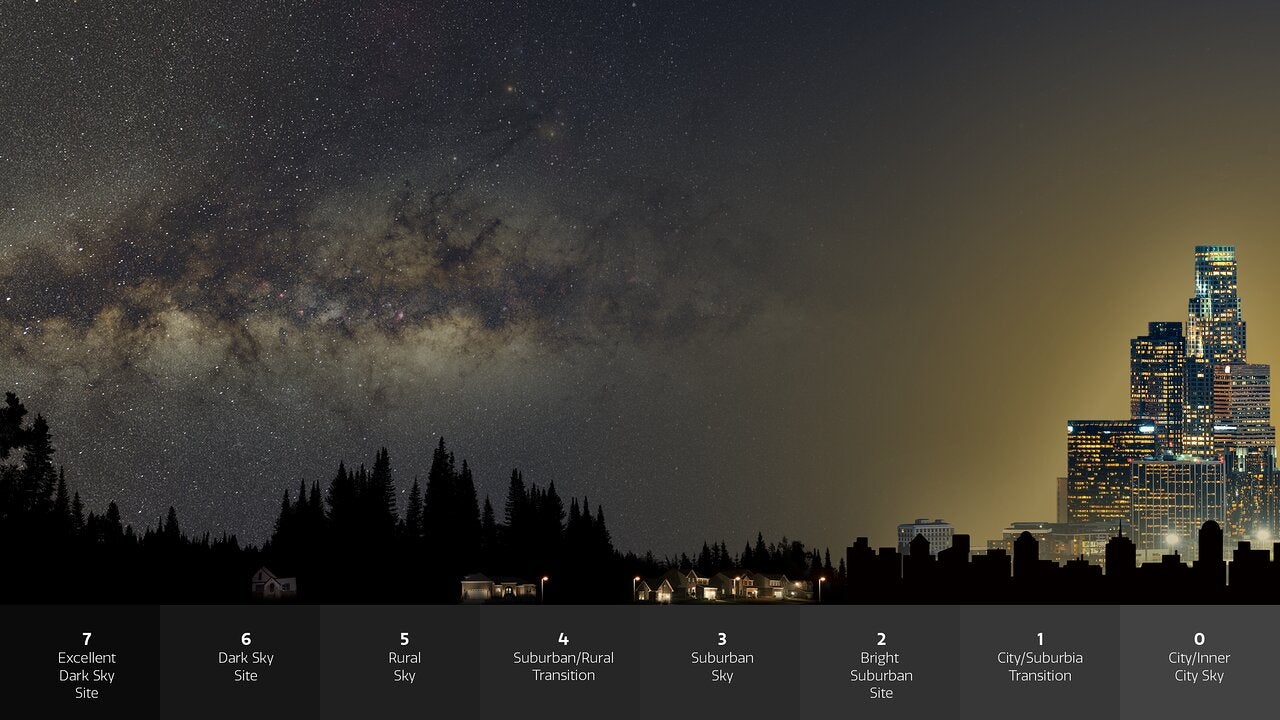

When I was a kid, my family lived in suburban Washington, D.C. This made being a budding amateur astronomer tough; most stars were invisible against the overhead glare from city lights. At best, there was only a hint of the diffuse Milky Way to see: the combined radiance of a hundred billion stars dimmed to near-nothingness by bright streetlamps and storefronts.

This is light pollution—human-generated illumination cast up into the heavens —causing the sky itself to glow and washing out the stars. Astronomers have known for years the situation is bad for stargazing, but it also has real and negative effects on the well-being of many living things—plants, animals and even human beings. More than 80 percent of humanity is affected by light pollution, their view of the skies being stolen away.

For most of us, the stars are, in essence, going out.

And every year it’s getting worse. How much worse, exactly, has been hard to say. While light pollution has been measured from space, orbiting satellites don’t detect light the same way the human eye does, so they may not yield results that match what we see from the ground. When people look at the sky, what is the change in sky brightness they perceive over time?

To find out, a team of scientists led by light pollution researcher Christopher Kyba of the GFZ German Research Center for Geosciences turned to what may seem a weirdly obvious detection method: human beings.

They used data from Globe at Night, a project run by the U.S. National Science Foundation’s National Optical-Infrared Astronomy Research Laboratory (NOIRLab), which uses citizen science to measure light pollution. The process is brilliantly simple. Volunteer participants are given a set of star charts (created by Jan Hollan of the Global Change Research Institute of the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic) that show the sky with a range of stars visible; one chart shows only the brightest stars, the next includes somewhat fainter stars, and so on down to the faintest stars visible to the naked eye under ideal conditions. Participants then observe the sky and compare the faintest stars they can see to the charts, choosing the one that best matches what they see.

Kyba and his team examined an astonishing amount of data from more than 50,000 citizen scientists from around the world who sampled their local sky brightness from 2011 to 2022. While there was considerable place-to-place variability—for example, on average, Europe saw a 6.5 percent increase in light pollution per year, while North America saw a 10.4 percent increase—the researchers found that globally, light pollution increased by 9.6 percent per year over the time period.

This may not sound like much, but it reflects an exponential growth rate similar to how compound interest accrues on a debt. A year-over-year growth of about 10 percent means sky brightness is doubling about every seven years. A moment’s thought should make clear why this is deeply troubling. As Kyba and his co-authors explained in their paper, published in the journal Science, if there are 250 visible stars in the sky when someone is born, by the time they’re 18 they’ll only see 100, and over that same period the sky will have increased in brightness by more than a factor of four.

This result is all the more alarming because of its potential implications for satellite-based measurements, which have recorded only a roughly 2 percent increase per annum. Based on their work, Kyba and his team argue that the satellites are severely underestimating the effects, blinding us to a looming future in which almost everyone loses sight of the stars.

Technological changes can account for much of this discrepancy. For example, Kyba and his colleagues point out that over recent years many older outdoor lights emitting redder light have been replaced by LEDs that shine brighter in blue—a color that scatters more easily in the atmosphere, and to which many Earth-observing satellites’ detectors are less sensitive. Moreover, satellites mostly see light shining straight upward, like that from poorly constructed street lights and cities, rather than horizontally cast rays from windows or billboards that can greatly affect observers on the ground.

All this extra light at night has a large effect on the life under it. Researchers have shown that it has negative impacts on many animals and plants; light pollution disrupts the great migrations of birds, the delicate blossoming of flowers, and even the luminous courtship of fireflies, to name just a few examples. It affects humans as well, possibly triggering insomnia among many other health problems.

In some ways this is reminiscent of the climate crisis: global in nature, difficult to notice day by day, and hard for individuals to grasp and mitigate on their own. However, I suspect that if global warming increased by some 10 percent per year we would have long ago tackled the issue head-on.

Worse, light pollution puts on a friendly face for many, implying that increased light at night automatically means increased safety. While this can be true in some cases — for example, illuminated roads making it easier for drivers to see at night — it can also make things worse; overly bright streetlights cast deeper shadows, making it easier for danger to hide from our ill-adjusted eyes. And, on average, this increased illumination just throws even more unwanted light upward.

So what can we do about our brightening skies?

There is a lot already happening. Groups like the International Dark Sky Association, or IDA, advocate not for more lighting but for more intelligent lighting; smarter street lights that concentrate their light downward is one example. Because these lights offer more efficient illumination, they save energy, too, eventually paying for themselves. The IDA offers advice on how to contact local authorities to install better fixtures and create ordinances to lower pollution. Many cities in the United States and other countries are designated Dark Sky Communities, ones that have shown “exceptional dedication to the preservation of the night sky” by discouraging wasteful lighting practices.

At the moment, simple awareness is one of our greatest benefits. Turning off your own outdoor lighting at night may not seem a big deal, but if you tell others, that helps. Awareness grows. Any cause like this needs a critical mass to get widespread notice, so everyone who participates can add to the solution.

Still, despite the recent successes in cities like Pittsburgh and Ft. Collins, Colo, such local solutions don’t readily translate to global progress. This isn’t easy; many areas in developing nations have dangerously insufficient lighting at night, and use wasteful greenhouse-gas-emitting fuels to power the meager light sources they have. More lighting can help them out of poverty, but at the cost of a larger increase in sky glow. Kyba et al.’s research didn’t cover developing nations well, so it’s not clear at what rate their light pollution is increasing, but it’s obvious enough that more efficient lighting would benefit these regions, too, if for no other reason than keeping costs down in the medium to long run.

In an epic thread on Twitter, lead study author Kyba goes over the methodology and results of the work, and includes some advice on what individuals can do. He suggests using targeted illumination rather than flood lighting, deploying outdoor lighting only when needed, and preferring light bulbs and LEDs that shine more red than blue to reduce how much scatters across the sky.

We do need bigger and smarter solutions. Certainly the physical and biological effects are a big concern, but there’s more at stake here: the loss of beauty and our connection to nature. The night sky is, quite simply, gorgeous, with treasures scattered among the stars. Going out under that velvet vault and watching a meteor shower or a lunar eclipse is a wonderful way to spend time with family and friends, or to simply decompress. To see the stars is to nourish the soul. I’ve seen (and heard) countless owls and coyotes and other wildlife while outside at night, and observing the heavens gives me a profound appreciation of the natural world around me. The awe of the night sky is very real.

This isn’t just a matter of a few inconvenienced astronomers. It’s the equivalent of shuttering the Louvre, of closing concert halls, of mowing down vast fields of wildflowers. I wonder how deep my own love of astronomy would have grown had I stayed in the suburbs of D.C., the stars not-so-gradually diminishing as I grew up. I struggled to see the skies through that miasma as it was, and it was only a profound love of astronomy that kept me going. Many people don’t even know that they—and their descendants—are losing this cosmic experience just over their heads.

We need the dark night sky, and it’s up to all of us to make sure it’s still there every time the sun goes down.

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the views expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those of Scientific American.