Light Pollution Is Bigger Threat To Astronomy Than Satellite Constellations – Forbes

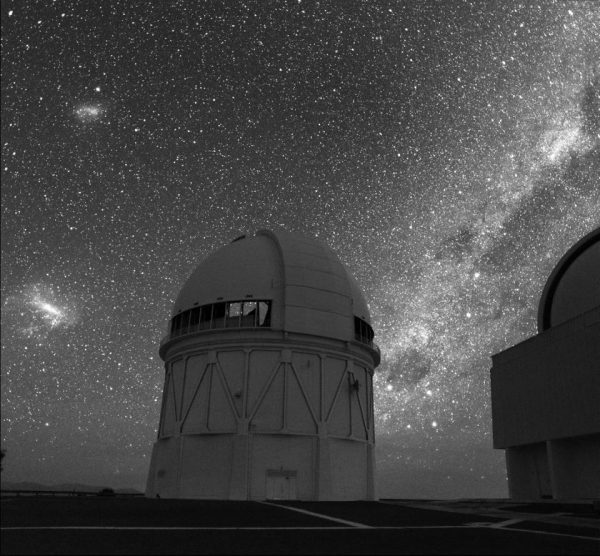

The CTIO 4-meter Blanco telescope, silhouetted against the Magellanic Clouds (at left) and the Milky … [+] Way, as seen from Cerro Tololo in Chile.

Roger Smith/NOAO/AURA/NSF

Artificial light pollution here on Earth poses more of a threat to ground-based astronomy than even the next generation of commercial satellite constellations, says a prominent Chilean astrophysicist.

At this moment, the biggest threat to Chilean astronomy and the international observatories operating in Chile is artificial light coming from the cities, Mario Hamuy, Head of the AURA (Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy) mission in Chile, told me in Santiago.

Large swaths of Chile’s northern Atacama Desert, the highest and driest on Earth, remain largely devoid of any sort of habitation and light as nighttime images of the area from space easily attest. But times are changing.

Given that since 1950 its current population of some 18 million people has tripled, it’s not surprising that even Chile suffers from artificial light pollution. The hope is that despite such light pollution Chile can maintain its primo status as a ground-based Valhalla onto the cosmos.

Why is Chile such a good spot for optical astronomy?

Aside from areas of the country that have high, dry desert conditions, Hamuy explains that the Humboldt current transports cold water up from the Antarctic which prevents the formation of clouds on the West side of the country. To the East, we have the high Andes which prevent clouds that form in the Atlantic to come over Chilean territory, he says.

As for light pollution?

AURA —- which operates observatories for a consortium of 47 U.S. institutions and 3 international affiliates —- was the first international observatory to start operations in Chile in 1963. And at that time, light pollution was not even an issue, says Hamuy.

The European Southern Observatory’s (ESO) Very Large Telescope (VLT) and its forthcoming Extremely Large Telescope (ELT) are not under immediate threat from ground-based light pollution. But Hamuy says that ESO does have a light pollution problem at its La Silla Observatory, which receives significant pollution from Chile’s Route 5 (the North-South Pan American Highway).

Astronomical seeing at AURA’s own managed observatories atop Cerro Tololo and Cerro Pachon which include the Gemini South telescope, the forthcoming Vera Rubin Observatory in central Chile, and the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory are also at risk.

Around the AURA observatories the main sources of artificial light are the cities of La Serena and Coquimbo, says Hamuy. But even smaller cities like Vicuna and Andacollo can create problems. Thus, AURA is working with these municipalities to mitigate artificial light pollution.

Specifically, LED lights from a public soccer stadium in Andacollo are pointing directly towards Cerro Tololo, says Hamuy. Thus, the city is redesigning the stadium lights so that they are pointed towards the lower atmosphere instead of the upper atmosphere, he says. This not only will save energy but will provide a much more uniform lighting system for the soccer players, Hamuy says.

The whole idea is to preserve humanity’s astronomical culture, heritage and ground-based observational access to the sky. As Hamuy points out, at midnight in June and July, Chile has a front row seat onto the center of our Milky Way galaxy as well as the two Magellanic Clouds, the nearest dwarf galaxies that you can see with the naked eye, says Hamuy. Both are wonderful labs to study stellar evolution, he notes.

A case in point happened 33 years ago this past February when a blue supergiant star exploded as a Type II Core Collapse supernova. Although there is still some debate about whether the explosion might have been caused by the merger of two stars, Supernova 1987A (SN 1987A) was first seen on February 23, 1987.

Located some 160,000 light years away in the Milky Way’s neighboring Large Magellanic Cloud, it’s known that at least one of its progenitors was Sanduleak 69202, a blue supergiant star of some 20 solar masses.

Among the hottest, most massive and short-lived types of stars known, as I noted in my book “Distant Wanderers,” SN 1987A “offered astronomers the first direct confirmation that heavy elements are produced in supernovae.”

Image obtained with the ESO Schmidt Telescope of the Tarantula Nebula in the Large Magellanic Cloud. … [+] Supernova 1987A is clearly visible as the very bright star in the middle right. At the time of this image, the supernova was visible with the unaided eye.

ESO

And Hamuy was one of the first astronomers to view this naked eye supernova. “This was a gift from the heavens,” said Hamuy, who notes his first job as a professional astronomer was making observations of this bright supernova on a small 16-inch telescope at Cerro Tololo.

Classified as a Core Collapse, hydrogen-rich supernova, NASA says that its expanding debris glowed in visible light with the power of 100 million suns for four months. Core Collapse supernovae are massive stars which undergo the core collapse of their iron cores.

They leave behind a compact remnant, either a neutron star or a black hole. In the case of SN 1987A, astronomers at Cardiff University in the U.K. announced last November that they had detected the long sought-after supernova’s neutron star core.

In the case of the mountaintop observations of SN 1987A, Hamuy says that without doubt the event triggered great interest in supernovae in general within the astrophysical community and led to new space- and ground-based supernova surveys.

In fact, without Chile’s naturally dark skies, much of the scientific advances in what we know about the cosmos might not have been possible.

1987A was the nearest supernova to explode in almost 400 years but it was still not in the Milky Way; so, we are still waiting for a galactic supernova, says Hamuy.

Let’s hope that when that happens, light pollution won’t interfere with future astronomers’ ground-based observations.

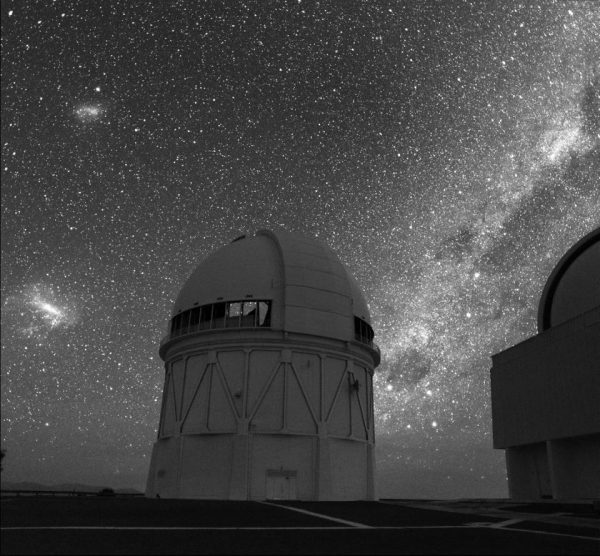

Aerial View of CTIO looking East.

Wikipedia