About 4.5 billion years ago, a young Jupiter collided head-on with a planetary embryo 10 times more massive than Earth. This giant impact formed Jupiter’s dilute core, which contains hydrogen and helium, one new study suggests.

Before NASA’s Juno mission launched to orbit and study Jupiter, scientists thought that the planet’s core was dense and compact. “Astronomers assumed that Jupiter has a small compact core with a mass ranging from 5 to 20 Earth masses,” lead study author Shangfei Liu of Sun Yat-sen University in Zhuhai, China, said in an email to Space.com.

This was assumed because Jupiter started off as a rocky and icy planetary embryo. However, studies using data from Juno found that the planet has an extended, dilute core — a core that is not only made up of rocky material and ice, but also hydrogen and helium. This “also means there is no sharp transition between the core and the envelope as we previously envisioned from planet formation theory,” Liu said. This dilute core is something that scientists determined could not form naturally.

Related: Behold! Jupiter Is a Breathtaking ‘Marble’ in This NASA Juno Photo

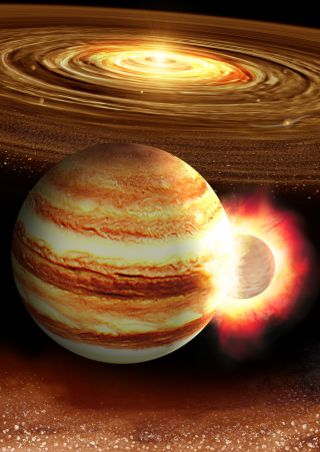

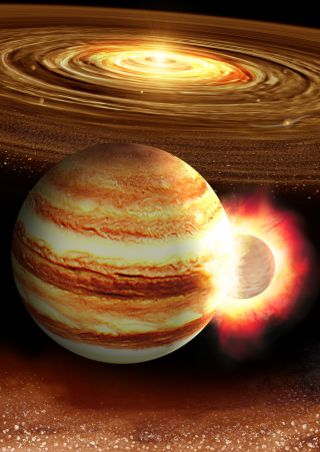

According to one new study, Jupiter’s dilute core was formed by a collision with a massive, planetary embryo. This impact can be seen in this visualization.

(Image credit: Astrobiology Center, Japan)

“That’s why we came up with the impact idea: Jupiter was smacked head-on by another massive planetary embryo (about 10 Earth masses) shortly after its formation,” Liu said. “Such a catastrophic collision destroyed Jupiter’s primordial compact core, and a dilute-core-like structure was formed.”

The cores of both the young Jupiter and the planetary embryo merged in this violent impact, the authors of this new study suggest. The materials from both of these cores partially mixed with Jupiter’s gaseous envelope, which can be detected in the planet’s structure still today.

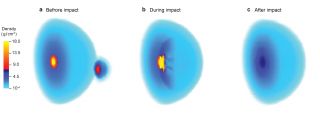

According to one new study, led by researcher Shangfei Liu, Jupiter’s dilute core was created by a collision with a massive planetary embryo. This figure from the study visualizes that collision.

(Image credit: Shangfei Liu)

When Jupiter began building the massive, gaseous envelope that surrounds its core, “its mass increases about 30 times in a fraction of a million years,” Liu said. This process, known as the runaway gas accretion stage, disturbed planetary embryos that were developing nearby.

“Through computational simulations, we show that there is at least 40% chance that Jupiter would collide with another planetary embryo in the next few million years,” Liu added.

The team determined that the developing planet that collided with Jupiter must have been about 10 times the mass of the Earth, because “smaller impactors cannot penetrate Jupiter’s massive envelope,” Liu said. Additionally, the collision must have been head-on, because if the object didn’t hit Jupiter directly, it would slowly sink toward the center instead of destroying the planet’s core, as it would have less impact energy.

This study was published today (Aug. 14) in the journal Nature.

Follow Chelsea Gohd on Twitter @chelsea_gohd. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.