Jupiter’s Great Red Spot may not be disappearing – Astronomy Magazine

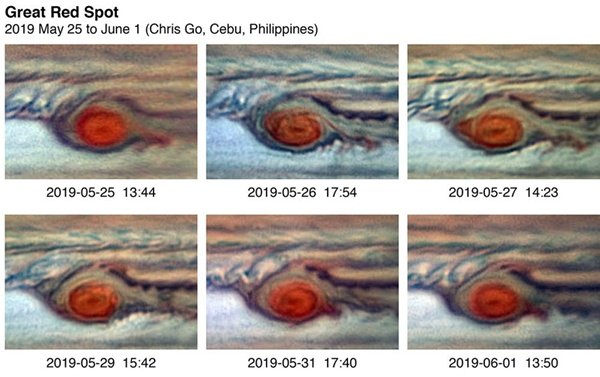

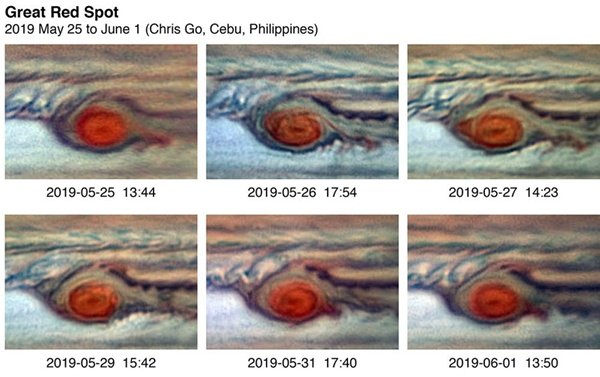

A (false color) series of images capturing the repeated flaking of red clouds from the GRS in the Spring of 2019. In the earliest image, the flaking is predominant on the east side of the giant red vortex. The flake then breaks off from the GRS, but a new flake starts to detach in the fifth image.

Chris Go

Two simultaneous events that led to flaking

Anticyclones merge with each other. However, anticyclones repel cyclones. In spring 2019, when the “flaking” was observed, the Great Red Spot was also observed to merge with a series of small clouds (likely small anticyclones) on its northwest side. Such mergers are common; Voyager 1 first observed these and they have subsequently been observed every few months. Typically, small anticyclones are not “digested” immediately, but produce lumps on the spot’s boundary that orbit around it, slowly migrating into the center.

I believe that the shedding of clouds from the spot as “flakes” and “blades” observed in 2019 was due to two simultaneous events: undigested lumps of merged anticyclones traveling along the spot’s boundary and a close encounter with one or more “unobservable” cyclones.

When a large anticyclone and smaller cyclone approach each other before repelling, they create a “stagnation” point near the boundary of the anticyclone where the local winds abruptly change direction, going off approximately perpendicular to their original directions. Think of two fire hoses aimed at each other so that their streams of water collide – the streams momentarily halt at the point of impact (the stagnation point) and then scatter outward. Any cloud or undigested lump on the spot that encounters a stagnation point will similarly shatter and flake away in opposite directions.

The numerical calculations of my Berkeley research group show that the recent observations of cloud shedding can be explained by the collision of undigested red clouds at the edge of the Great Red Spot with stagnation points produced during a close encounter with a cyclone.

Pieces of the red cloud scatter outward from the stagnation point, appearing as flakes and blades. Neither the mergers that created the lumps nor the close encounters with cyclones are unusual by themselves, but it is not that common for them to occur at the same time. However, neither event is a sign of ill health for the Great Red Spot. My colleagues and I believe it will survive for many more years.

Philip Marcus, Professor of Mechanical Engineering, University of California, Berkeley

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.