Is It Time For Voice Technology To Kill Touchscreens? – Forbes

Humans and objects have had a long love affair. Simple tools, as well as sophisticated software are all extensions of our physical bodies. We can trace human progress and wellbeing to the level of sophistication of the tools we have created, and by doing so, the augmentation of our abilities to travel, build, communicate, and create. Since tools are so critical to our existence and prosperity, the way we interface with these tools is also of great importance.

So important is the interface between humans and the machines we operate, that when a new medium arises that has the power to redefine this interface, it is a real revolution which doesn’t quite happen every day.

As you read this, you are most likely holding a device with a touch screen or mouse in your hand. These two tools that conquered the world of the human-machine interface are the de-facto way people around the world interface with machines. Maybe you are the assistant to the CEO of a Fortune 500 company. Perhaps you are a hacker in Ukraine or an engineer working on an oil rig. Whatever the case may be, we are all using the same interface to operate today’s machines, i.e., mobile, desktop, or industrial computers.

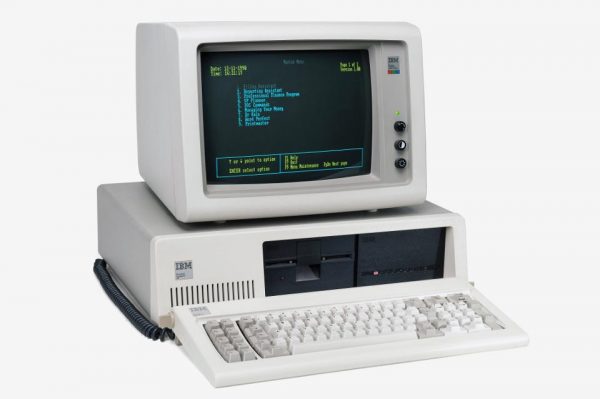

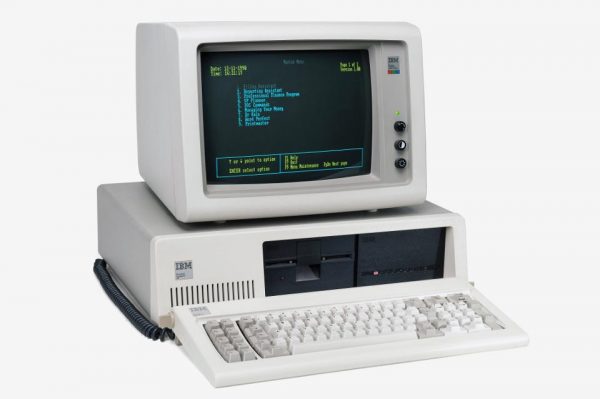

In the early 80’s my go-to word processing application was something called “WordStar.” Two-thirds of it’s screen contained keyboard shortcut reminders: CTRL+U – underline, CTRL+T single tab, F1 – new paragraph, and so on. Unlike today’s top gamers who choose to use keyboard shortcuts, back then, the keyboard was the only option—and it was tedious. So no wonder the world jumped with joy when the computer mouse and window style screens appeared.

We grabbed that mouse and never let go.

How on earth did we manage to operate these machines without a mouse?

Future via Getty Images

As much as the mouse reigned supreme in the world of PC’s and laptops, it contributed nothing to the efficient manipulation of mobile devices. Yes, there were early attempts with the keyboard and joystick of Blackberry devices, but once Mr. Jobs showed the world the beauty and ease of touchscreens, he also introduced the only other reason we will let go of our mouse, that is to grab our mobile phone.

Now there is a new gunslinger in town and her name is voice. Rumor has it that she’s looking to take down the mouse and touchscreen in one shot. But is it possible? Can voice interfaces displace our beloved mouse and touchscreen?

Let’s give this threat the attention it deserves.

There is a common misconception around voice technologies wherein people often confuse the ability to transcribe or understand the spoken word with other digital capabilities such as “search” or analytics, which are typical for input interfaces like typing or scanning documents. Part of this is voice—understanding what is said by the user. The rest is operating digital tools and services that are common to Voice, but also many other operations.

Here’s an example: As you stand in your kitchen washing the dishes, you remember that you need to check the weather for your upcoming trip. Your hands are wet, and you don’t want to grab your mobile phone, because who knows if it’s as watertight as advertised. So, you say loudly “Alexa, what is the weather in NYC tomorrow?” In response, Alexa speaks the weather forecast to you.

What just happened from a technical perspective?

No mouse, or keyboard, just say the magic word

AFP via Getty Images

First, you activated the device via its magic “wake word.” The specific word for this device is “Alexa,” but each of our devices require a different word depending on who they are manufactured by. Next, natural language processing kicked into gear and converted your spoken word into digital bits and bytes that were then sent to the cloud. Finally, using machine learning algorithms that have already trained in your language, the machines in the cloud make sense of what you said. At this point, “voice technology” ends. Now, let’s use more conventional tools. Amazon, or Google, or Apple, needs to search for the answer to your question, maybe by using an API to a digital weather service. Once the correct services find a solution, voice technology is back again to construct the answer, activate your Alexa device, and bam, you know the weather.

Just like touchscreen technology, voice is an input mechanism. When you use your touchscreen to pull up the best route home from a restaurant, your touch screen itself doesn’t chart the route. By pressing the icon on your touchscreen, you activate an app that enables a service that finds the course. In the same way, we can’t say that voice is responsible for finding out what the weather will be tomorrow.

For Voice to take over from touch screens, or to kill our beloved mouse, it first has to clear a few hurdles.

The race is on, but for Voice to win it first needs to clear a few hurdles

Getty Images

Wake Words Are An Annoying Necessity

Take, for example, the business of “wake words.” At home, when your spouse wants to get your attention, they may call out to you using different words depending on the situation. If he or she addresses you with a nickname or term of endearment, such as darling or honey, that may mean something entirely different than if they were to address you by name. With voice interfaces, you need to get the attention of the device you are after by waking it up, and no amount of context can help you do this. In other words, if you don’t know the specific wake word for a given device, it will not respond to anything you say. No amount of ‘darlings’ or ‘honeys’ will get you there.

What Can This Device Do?

We were after finding out the weather, but does this device carry this functionality? Maybe it can only play music, or turn off the lights. With graphical user interfaces, we can browse the selection of features the device offers, but voice-activated devices are less foretelling. There is just no knowing what they are capable of doing.

Some Conversations Are Harder To Understand

Let’s talk about the question we asked: “What will the weather be in NYC tomorrow?” This is a pretty common question. No abbreviations or potentially confusing lingo were used. There are plenty of digital sources that can be used to train machines to understand this sentence.

Time to dial up the difficulty a notch higher. Consider a scientist uttering a complex formula with lots of very niche industry jargon as he works in his lab. This is not a common language, and training a machine to understand this will require it to have access to digital media such as research papers or scientific articles. Difficult, but not impossible, as there is a wealth of scientific digital content out there. Now, consider the type of conversation a crew working next to a drilling machine in an open mine would have. Open mine workers don’t write many research papers nowadays, so the data required to train a machine to understand this specific industry lingo is much harder.

Too Noisy, Can You Please Repeat?

In environments that do not have background noise, like at home or in the lab, it’s reasonable to expect voice-activated devices to be able to hear what you say. But how about in the case of the mine workers? Or people in a coffee shop, or in a car with a few people talking at the same time? In these instances, it will be much harder for voice technology to hear what is being said.

What this all boils down to is that voice technology is great for some use cases. For us as innovators, determining which use-cases work best is the critical question to answer.

What To Consider When Innovating With Voice

If you are thinking about using voice as the interface for your next application, consider the current constraints of the technology: wake words, onboarding users on the available functionality, the ability to navigate between functions, how common or industry-specific the language being used, and the environmental conditions. This is not to say that there aren’t great uses for voice technology; it’s to say that the mouse and touchscreens are safe for the foreseeable future.