Only three nations have successfully landed spacecraft on the moon — the United States and the Soviet Union during the space race of the 1960s and 1970s, and more recently, China. (An Israeli nonprofit attempted to send a lander named Beresheet to the moon earlier this year, but it crashed.)

If all goes well on Monday, and in the weeks ahead, India will become No. 4 with Chandrayaan-2, a homegrown mission to the moon that aims to demonstrate the technological achievements of one of the largest countries on Earth.

Liftoff is scheduled for Monday at 2:51 a.m. local time from the Satish Dhawan Space Center along the southeastern coast of India. In the United States, it will still be Sunday — 5:21 p.m. Eastern time.

The spacecraft is on top of India’s most powerful rocket, a Geosynchronous Satellite Launch Vehicle — Mark III.

The Indian Space Research Organization, or ISRO, which is India’s equivalent of NASA, is likely to stream coverage of the launch on its website and on Facebook.

Doordarshan, a public broadcasting network in India, is also likely to provide live video of the launch.

[Sign up to get reminders for space and astronomy events on your calendar.]

Not until Sept. 6 under the current timetable.

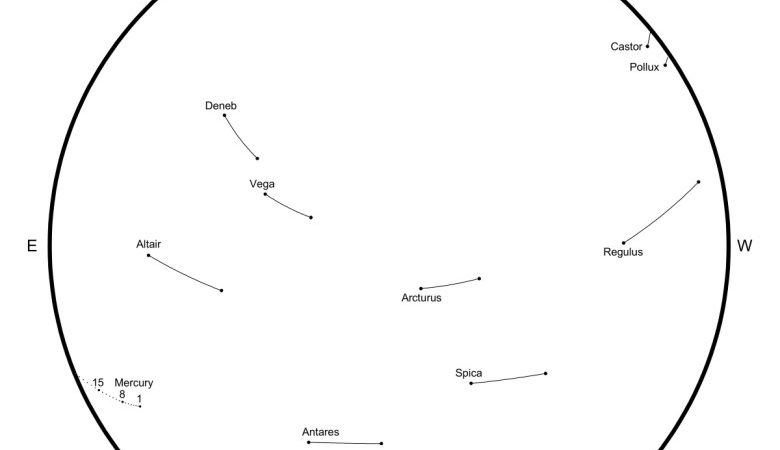

Chandrayaan-2 will take a slow, fuel-efficient path to the moon, similar to the trajectory that the Israeli Beresheet spacecraft followed. Through repeated firings of its thrusters, it will stretch out its elliptical orbit until it is captured by the moon’s gravity. Additional thruster firings will then make the orbit around the moon more circular, a prelude to the landing.

The spacecraft consists of multiple pieces:

-

an orbiter;

-

a lander named Vikram, after Vikram A. Sarabhai, the father of the Indian space program;

-

and, a six-wheeled rover named Pragyan, which means “wisdom” in Sanskrit.

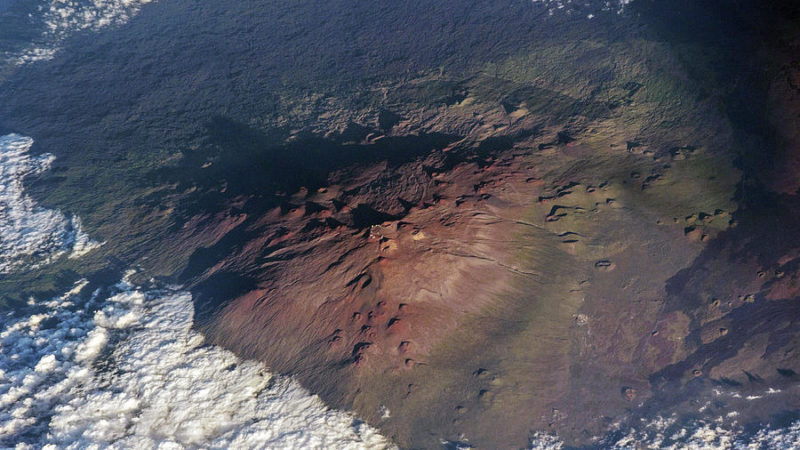

In September, the lander (which will be carrying the rover) will detach from the orbiter and head to a landing site near the South Pole of the moon.

The rover carries a couple of instruments to measure the composition of moon rocks and soil. The lander carries instruments to measure moonquakes, temperatures a couple of inches into the soil and charged particles from the sun in the extremely tenuous lunar atmosphere.

The lander and rover are expected to operate just a couple of weeks.

The orbiter carries a suite of instruments, including cameras and spectrometers, and is designed to operate at least a year.

For people in India, the space program is a demonstration of their country’s emerging technological capabilities. The Chandrayaan-2 lander and rover will explore a spot near the lunar South Pole, which is an intriguing region that no one has seen up close yet. Water ice exists deep within eternally shadowed craters near the poles.

Chandrayaan-2 will be heading not into a crater but instead to a high plain between two craters.

India’s Going to the Moon, and the Country Is Pumped

India will launch an unmanned rover into space on Monday. If successful, India will join a select group of nations capable of reaching the moon.

It is Hindi for “moon vehicle.”

As the 2 in Chandrayaan-2 indicates, India has already sent one spacecraft to the moon. The orbiter Chandrayaan-1, launched in 2008, operated for 10 months and helped confirm the presence of water ice in the lunar craters.

India also launched an orbiter to Mars in 2013 that continues to orbit the red planet, and in 2017, an Indian rocket deployed 104 satellites, a record for a single launch.

India’s space missions have cost a fraction of those from bigger space agencies like NASA and the European Space Agency, but they have also generally carried simpler payloads. That is also true of Chandrayaan-2, which cost less than $150 million.

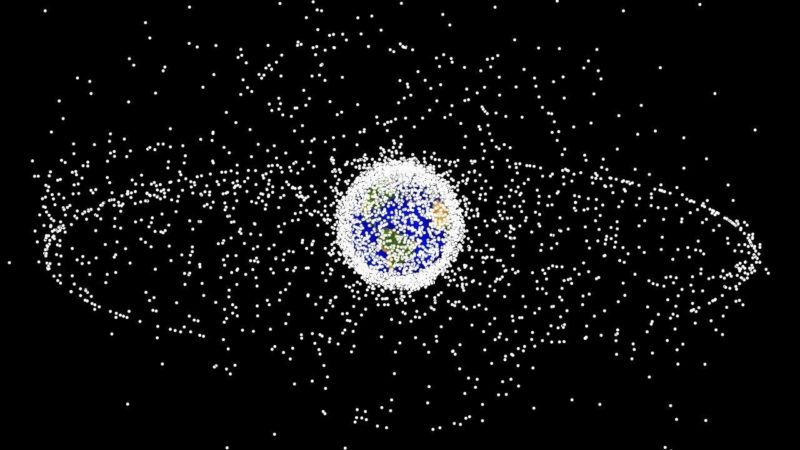

In March, India also demonstrated a less friendly space capability, an antisatellite test that scattered hundreds of pieces of debris. China, the United States and Russia have developed similar weapons.

ISRO’s plans include additional robotic missions to Venus, Mars, the moon and the sun.

India is also working on flying its astronauts to Earth orbit on Gaganyaan, or “orbital vehicle.” A crewless test is scheduled for December of next year; the first flight with people aboard is scheduled for 2022.

China landed Chang’e-4, a robotic lander, on the far side of the moon in January. The unsuccessful landing attempt by Israel’s Beresheet occurred in April.

The Trump administration is aiming for the United States to return astronauts to the moon in 2024, and NASA is also paying private companies to carry scientific payloads to the lunar surface, potentially as soon as next year.