BANGALORE, India — India’s attempt to land a robotic spacecraft near the moon’s South Pole on Saturday appeared to end in failure.

The initial parts of the descent went smoothly. But less than two miles above the surface, the trajectory diverged from the planned path. The mission control room fell silent as communications from the lander were lost. A member of the staff was seen patting the back of K. Sivan, the director of India’s space program.

He later announced that the spacecraft was operating as expected until an altitude of 2.1 kilometers, or 1.3 miles. “The data is being analyzed,” he said.

The partial failure of the Chandrayaan-2 mission — an orbiter remains in operation — would delay the country’s bid to join an elite club of nations that have landed in one piece on the moon’s surface.

If the spacecraft crashed — although a communications glitch was also possible — it occurred during a period that Dr. Sivan had called “15 minutes of terror.” A series of steps had to be completed by computers on board the spacecraft in the correct sequence, with no opportunity for do-overs.

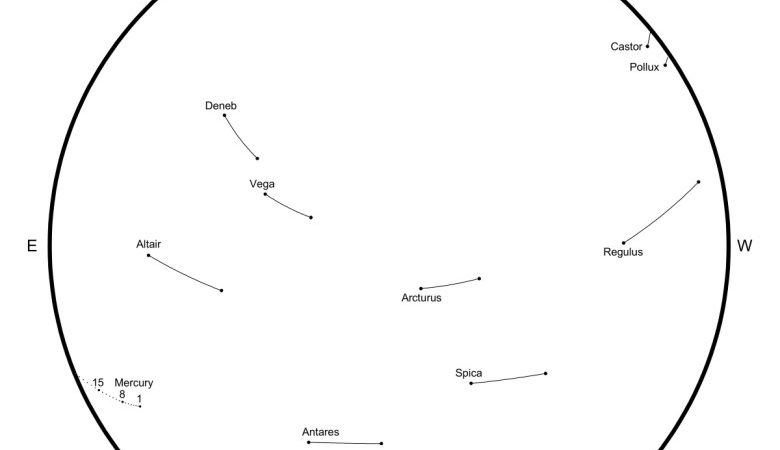

[Sign up to get reminders for space and astronomy events on your calendar.]

This was the third attempted spacecraft landing on the moon this year. In January, China landed the first probe ever on the far side of the moon. The lander and accompanying rover have been operating since then.

An Israeli nonprofit sent a small robotic spacecraft named Beresheet to the moon, but its landing attempt in April went awry in a manner similar to Chandrayaan-2. The initial descent went as planned, but then communications were lost near the surface. It was later discovered that a command to shut off the engine was incorrectly sent.

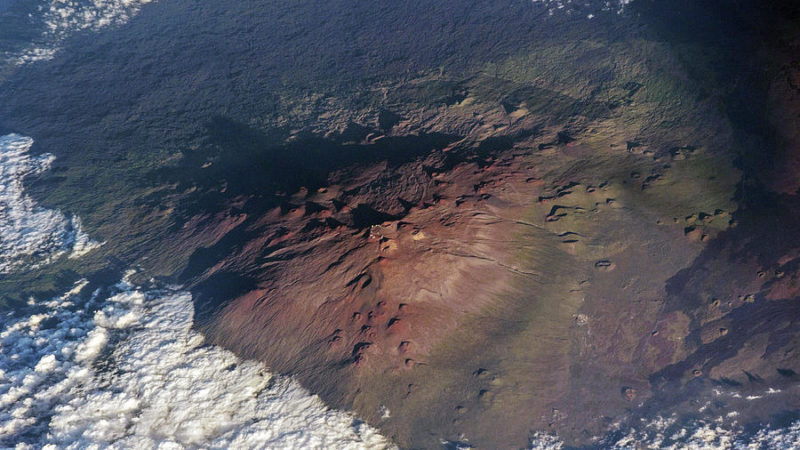

Chandrayaan-2 launched in July, taking a long, fuel-efficient path to the moon. Earlier this week, the 3,200-pound lander, named Vikram after Vikram A. Sarabhai, the father of the Indian space program, separated from the orbiter and maneuvered toward the moon’s surface.

Fifteen minutes before the planned landing, the Vikram lander was traveling at more than 2,000 miles per hour at an altitude of about 20 miles. Four of its engines fired to quickly slow it down as it headed toward its landing site on a high, flat plain near the South Pole. Later in the landing process, it appeared that Vikram was descending too fast and then data from the spacecraft ended.

The moon is littered with the remains of spacecraft that have tried and failed to land in one piece. Two American craft, from the robotic Surveyor series that helped blaze the trail for Apollo, crashed in the 1960s. Several probes from the Soviet Luna program also collided with the moon’s surface.

The makers of Beresheet and Chandrayaan-2 both noted the low cost of their missions — $100 million to $150 million, which is much cheaper than those typically launched by NASA and the European Space Agency. NASA is currently trying to tap into entrepreneurial innovation for upcoming robotic moon missions; the first of these low-cost trips is scheduled to launch in 2021.

The outcomes of the Indian and Israeli missions highlight that lower costs can mean higher risk of failure, which NASA will need to adjust to as it pursues a lower-cost approach.

While India may not have stuck the landing on its first try, its attempt highlighted how its engineering prowess and decades of space development have combined with its global ambitions.

It remains to be seen what the crash will mean in India’s domestic politics. Prime Minister Narendra Modi, the country’s nationalist leader, has embraced the country’s space program to raise India’s brand on the global stage and make Indians feel fired up about their nation’s growing strength.

“This is all about national pride,’’ said Pallava Bagla, co-author of a book about Indian space exploration and a dedicated space journalist.

Applause swept through viewing parties in Bangalore for most of the lander’s descent. At the command center, scientists rose to their feet as they tracked the mission’s progress. When communication was abruptly lost, Sathya Narayanan, 21, an educator with Astroport, a group in Bangalore that spreads awareness about astronomy, said his heart dropped.

“At this point, it is a partial failure,” he said. “We will push until the end.”

While the mission may briefly soften the muscular nationalism espoused by Mr. Modi, whose government is already facing challenges from job losses and international criticism of his recent moves in the disputed territory of Kashmir, the prime minister tried to reframe Saturday’s landing attempt as an opportunity for improvement in brief remarks after contact was lost.

Hours later and back at the space center in Bangalore, the prime minister greeted the scientists, engineers and staff of the space agency after delivering a motivational speech that was broadcast nationally in India. He stopped short of stating explicitly that the lander had failed.

“We came very close, but we will need to cover more ground in the times to come,” he said.

Later in his address, Mr. Modi added, “As important as the final result is the journey and the effort. I can proudly say that the effort was worth it and so was the journey.”

Space has become a popular topic in India.

In some Indian cities, posters for Chandrayaan-2 have been plastered on giant billboards. Schoolchildren in space classes are launching rockets made from empty plastic soda bottles. In July, when India sent up the rocket carrying the lander, millions watched the live broadcasts of the rocket cutting into the sky on top of a funnel of fire.

The moon mission has been years in the making for ISRO, India’s version of NASA, founded in 1969, when components of rockets were transported by bicycles and assembled by hand.

Hundreds of millions of Indians still live deep in poverty; India’s philosophy is that space development can be used for human development. Its satellites help predict storms and save countless lives by sending out early warnings. And it hopes future business opportunities in space will create more work that lifts up more Indians.

While the landing may have failed, India could try for the moon again. And it also plans to build future robotic explorers headed for Venus, Mars and the sun. In the next decade, it intends to send Indian astronauts into Earth orbit aboard its own spacecraft for the first time.

_____

Jeffrey Gettleman reported from New Delhi. Hari Kumar and Kai Schultz reported from Bangalore. Kenneth Chang reported from New York.