Hubble finds the best evidence yet for elusive midsized black holes – Astronomy Magazine

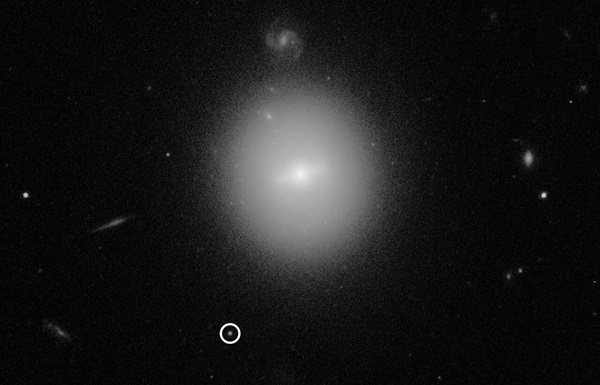

The Hubble Space Telescope captured this image of the suspected intermediate-mass black hole 3XMM J215022.4-055108 (circled). The black hole seems to be located in a dense star cluster some 800 million light-years away.

NASA, ESA, and D. Lin (University of New Hampshire)

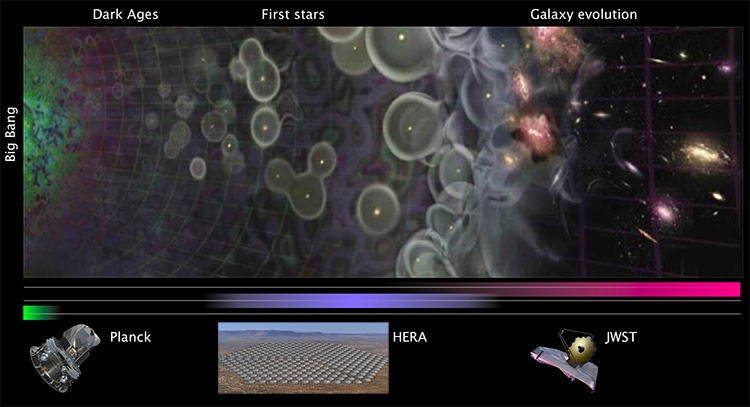

Intermediate-mass black holes are a curious example of a type of astronomical object astronomers believe exists but haven’t managed to prove yet. There’s plenty of evidence for stellar-mass black holes, the kind that massive stars create when they explode at the end of their lives. And there’s also lots of proof for supermassive black holes, including last year’s Event Horizon Telescope image of the shadow of the giant black hole at the center of the galaxy M87.

Though the exact definitions for different types of black holes depend on who you ask, stellar-mass black holes range from just a few to 100 times the mass of the Sun, and they are largely scattered throughout galaxies. Meanwhile, their supermassive brethren range from millions to billions of solar masses and lurk in the centers of most — if not all — large galaxies.

But how do star-sized black holes beef up into supermassive ones? Astronomers think stellar-mass black holes grow by consuming anything that’s nearby — like stars, planets, nebulae, and spaceships (OK, maybe not spaceships). By gorging on what they can, these small black holes eventually reach a new weight class and become intermediate-mass black holes, which range from about 100 to 1 million solar masses. The problem with pinpointing these midsized black holes, however, is that they have already gobbled everything in their local neighborhood, yet they remain too small to source their meals from the larger galactic environment.

In other words, they suffer from classic middle child syndrome. They’re quiet, well-behaved, and therefore invisible — at least most of the time.

Very rarely, though, a star may stray too close to an intermediate-mass black hole, where the unimaginably strong pull of the black hole’s gravity shreds the star. As the stellar material circles the black hole like water whirling around a drain, it violently grinds together, causing the black hole’s surrounding accretion disk to sporadically light up. These cosmically brief blips are the primary way astronomers hunt midsized black holes, and it’s exactly what these researchers think they’ve seen with 3XMM J215022.4-055108.