The Rev. George C. Coyne, a Jesuit astrophysicist who as the longtime director of the Vatican Observatory defended Galileo and Darwin against doctrinaire Roman Catholics, and also challenged atheists by insisting that science and religion could coexist, died on Tuesday in Syracuse, N.Y. He was 87.

His death, at a hospital, from complications of bladder cancer, was announced by the Jesuit-run Le Moyne College in Syracuse, where he had been a professor of religious philosophy after retiring from the observatory in 2006.

Recognized among astronomers for his research into the birth of stars and his studies of the lunar surface (an asteroid is named after him), Father Coyne was also well known for seeking to reconcile science and religion. He applauded Pope Francis for addressing the role that humans play in climate change, and he challenged alternative theories to evolution like creationism and intelligent design.

“One thing the Bible is not,” he told The New York Times Magazine in 1994, “is a scientific textbook. Scripture is made up of myth, of poetry, of history. But it is simply not teaching science.”

Brother Guy Consolmagno, the current director of the Vatican Observatory, said in an email that Father Coyne “was notable for publicly engaging with a number of prominent and aggressive opponents of the church who wished to use science as a tool against religion.”

Among those he engaged on the debate stage and in print were Richard Dawkins, the English evolutionary biologist and atheist, and Cardinal Christoph Schönborn of Vienna, who, in an Op-Ed article in The New York Times in 2005, defended the concept that evolution could not have occurred without divine intervention.

During Father Coyne’s tenure, the Vatican publicly acknowledged that Galileo and Darwin might have been correct. Brother Consolmagno said it would be fair to say that Father Coyne had played a role in shifting the Vatican’s position.

While the church formally acknowledged in 1992 that it had “erred in condemning Galileo” in 1633 for promoting the theory that Earth revolved around the sun, Father Coyle was among the critics who complained that the admission was not only too late but also too little.

In 1996, Pope John Paul II, without defining evolution, said that it was “more than just a hypothesis.” His statement that Darwin’s views had “progressively taken root in the minds of researchers, following a series of discoveries made in diverse spheres of knowledge,” suggested that at least in public schools, religious faith and the teaching of evolution could coexist.

In an article in the English Catholic weekly The Tablet in 2005, Father Coyne sought to reconcile religion with evolution.

“God in his infinite freedom,” he wrote, “continuously creates a world that reflects that freedom at all levels of the evolutionary process to greater and greater complexity. He is not continually intervening, but rather allows, participates, loves.”

He went further by finding fault with intelligent design.

“If they respect the results of modern science, and indeed the best of modern biblical research,” he wrote, “religious believers must move away from the notion of a dictator God or a designer God, a Newtonian God who made the universe as a watch that ticks along regularly.”

He added, “Perhaps God should be seen more as a parent or as one who speaks encouraging and sustaining words.”

George Vincent Coyne was born on Jan. 19, 1933, in Baltimore, the third of nine children of Frank and Elizabeth (Brune) Coyne. His father was a traveling clothing salesman, his mother a homemaker. He is survived by two brothers, Thomas and Francis.

After being tutored by a nun on weekends (“no Saturday afternoon baseball or basketball for me,” he recalled), he won a scholarship to Loyola High School in Blakefield, Md.

He joined the Society of Jesus when he was 18 and attended a Jesuit novitiate in Wernersville, Pa., northwest of Philadelphia, where his Greek and Latin literature professor imparted a passion for math and astronomy.

Father Coyne earned a bachelor’s degree in math and a licentiate in philosophy from Fordham University in 1958 and then a doctorate in astronomy from Georgetown University. He completed a licentiate in sacred theology at Woodstock College in Maryland and was ordained a priest in 1965.

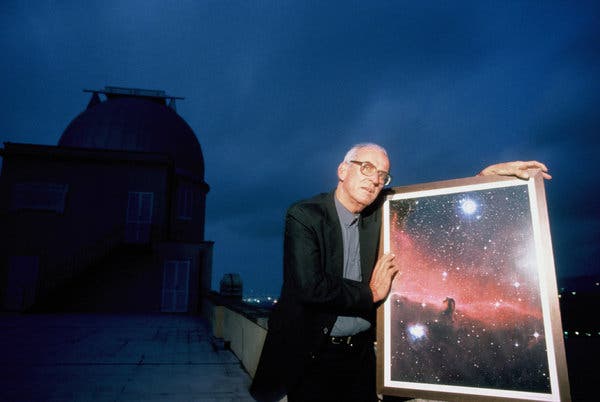

He joined the Vatican Observatory as an astronomer in 1969, taught at the University of Arizona’s Lunar and Planetary Laboratory and directed its Catalina Observatory. He was appointed director of the Vatican Observatory by Pope John Paul I in 1978 and was its longest-serving director, holding the post for nearly three decades.

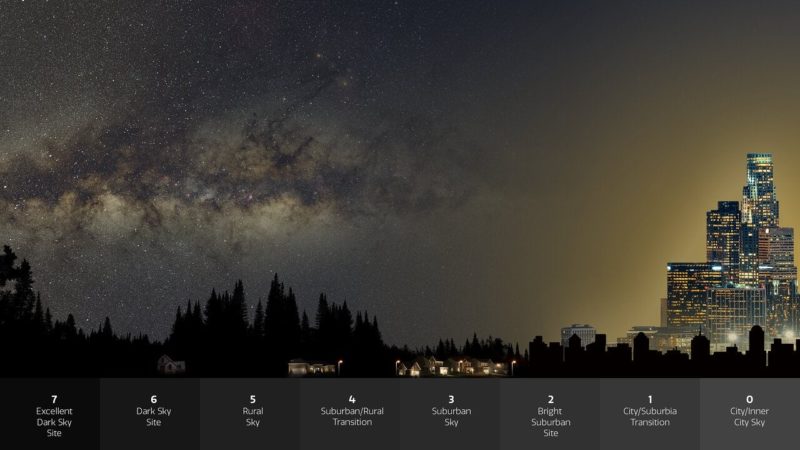

Father Coyne presided in 1993 when the observatory mounted a new Advanced Technology Telescope on Mount Graham in southern Arizona. (Light pollution at the observatory’s historic headquarters in Castel Gandolfo outside Rome had prevented the telescope from being installed there.) He established a research group at the University of Arizona and organized a summer program for graduate students.

In the 1990s, Father Coyne arranged conferences at the Vatican Observatory in collaboration with the Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences, a program of the Graduate Theological Union, in Berkeley, Calif.

“Father Coyne oversaw the modernization of the observatory’s role in the world of science,” Brother Consolmagno said. “He essentially re-founded the Specola Vaticana,” using the Italian name for the observatory, which dates to at least the 18th century.

After retiring in 2006, Father Coyne was president of the Vatican Observatory Foundation until 2011, when he was appointed to the McDevitt chair of religious philosophy at Le Moyne. He held that position at his death.

“George was one of the pre-eminent figures in the Catholic world who could speak intelligently and articulately about both science and faith,” said the Rev. James Martin, editor at large of America, the Jesuit magazine. “And George, by nature a humble man, could often dazzle.”

In the Times Magazine interview, Father Coyne was asked, “How can you describe the universe as a vast empty infinitude, largely uninhabited, and still believe in — ”

“The centrality of man in the universe?” he interjected, completing the reporter’s thought.

“There’s no doubt about it,” he went on. “To our own knowledge of ourselves, we are unique in creation because of our self-reflexivity. I can know myself knowing. I am having a conversation with you, and I can remember that conversation. To this, the Catholic Church comes along and says, ‘The reason this is true is because you have an individual soul.’”