The president proposes and Congress disposes.

So goes the standard description of the constitutional process by which our republic is governed. Judging from the news headlines, you might think this process has not been friendly lately to the scientific community. Again and again, the Trump administration has proposed drastic cuts to the research budgets of the Department of Energy, the National Science Foundation, NASA and other agencies.

Quietly, however, Congress often has gone the other way and handed out increases. In February, the Congress passed, and President Trump finally signed, a spending bill for 2019, averting another government shutdown. Lost amid the collective sigh of relief and the hoopla about President Trump’s wall was the news that astronomers had won a key victory: A pair of cosmically ambitious telescopes were rescued from possible oblivion.

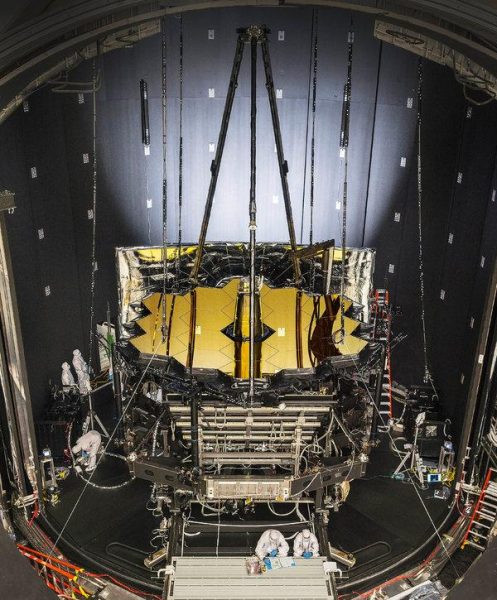

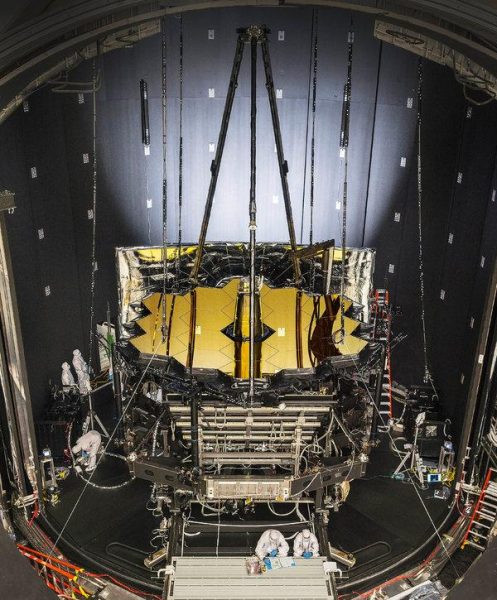

One of them, the James Webb Space Telescope, NASA’s long-promised successor to the Hubble Space Telescope, was designed to peer deeper into space and time than any optical eyes before it, to study the earliest stars and galaxies of the cosmos. But as of last year, it was deep in the red.

In the 1990s, the Webb telescope was expected to cost about $800 million. But the price kept growing, threatening to suck money from NASA’s other science programs. In 2011, Congress put a hard cap of $8 billion on its cost. Then an accident in 2018 at Northrop Grumman, the telescope’s main contractor, added another billion to the projected cost, putting the telescope or other NASA missions in danger of being trimmed or canceled.

The other telescope, the Wide Field Infrared Survey Telescope, or Wfirst, was designed to search for exoplanets, investigate the mysterious “dark energy” apparently speeding up the expansion of the cosmos and, perhaps, elucidate the fate of the universe. But Wfirst has always lived in the Webb telescope’s political and budgetary shadow.

Each time Webb was delayed or over budget, the dark-energy mission was pushed further into the uncertain future. Many astronomers feared that the Webb’s most recent cost overrun would come at the expense of Wfirst. Indeed, last year in its 2019 budget proposal, the Trump administration recommended that Wfirst be canceled outright.

But in the new spending bill, Congress raised the cap on Webb by $800 million, making the project whole again, for now. And Congress endorsed the Wfirst mission, with a cap of $3.2 billion on its cost. That will make things tight, since the estimated cost of the telescope recently rose to $3.6 billion. But it beats cancellation.

“The bipartisan support in Congress has kept the mission alive,” said David Spergel, an astrophysicist at Princeton and the Flatiron Institute in Manhattan, and co-chairman of the Wfirst science team, said in an email.

A similar theme runs through the last couple of years. “Over the past two budget cycles, Congress has indeed rejected the Trump administration’s proposed topline budget cuts to federal agencies that fund science,” said Mitch Ambrose of the American Institute of Physics, which tracks federal spending on research.

Consider the final 2019 budget: Mr. Trump proposed a 5 percent cut in NASA’s space science, but Congress made it an 11 percent increase, to $6.9 billion. The president wanted to cut the National Science Foundation budget by 4 percent, but Congress raised it by the same amount, to $8.1 billion.

The Geological Survey saw an even more sizable transformation. The administration proposed cutting its budget by $250 million, or about 21 percent. That would have slashed support for Climate Science Centers, which study the regional effects of climate change, and for research on carbon sequestration. Congress rejected those cuts, allotting the climate centers $25 million, only a shade less than in recent years. The Geological Survey as a whole received a one percent raise, to $1.2 billion.

Even the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, with its politically sensitive mission to study climate and weather, received a 3 percent increase, worth $16 million, to its $566 million budget for science for 2019. The Trump administration had proposed a 41 percent cut — a potentially devastating blow to the agency. By comparison, the president’s border wall would cost about $5.7 billion.

“Though this administration has regrettably chosen to ignore the findings of its own scientists in regards to climate change, we as lawmakers have a responsibility to protect the public’s interest,” Representative Eddie Bernice Johnson, a Democrat from Texas, said in a recent meeting of the House Science Committee, which she now heads.

Lamar Alexander, the Republican chairman of the Senate’s Appropriations Subcommittee on Energy and Water Development and Related Agencies, expressed the same sentiment last spring in a statement to his committee.

“Over the last three years, Congress has developed quite a consensus on science and research,” he said, noting in particular its agreement on medical research and supercomputing. “I would tell President Trump and the Office of Management and Budget that science, research and innovation is what made America first, and I recommend that he add science research and innovation to his ‘America First’ agenda.”

Not all is rosy in the realms of science policy. Since 1997, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has been discouraged from studying guns and violence by the so-called Dickey Amendment, which prohibits the C.D.C. from promoting gun control. Last year Congress affirmed that the C.D.C. could study the causes of gun violence, but provided no money for such research.

In an email, Julie Eschelbach, spokeswoman for the agency said, “Although C.D.C. does not receive direct funding for firearm-related research, C.D.C. has and continues to support data collection activities and analyses to document the public health burden of firearm injuries in the U.S.”

And 86 percent of Americans, a majority of both Democrats and Republicans, favor spending more money on science, according to a recent poll by Hart Research and Echelon Insights.

Once upon a time — in Einstein’s day, for example — it might have been considered unseemly for scientists to step outside their laboratories and make their case to the public. Today, organizations such as the American Astronomical Society and the American Association for the Advancement of Science have programs that teach young scientists how to do just that.

That work is unlikely ever to be finished. Mr. Trump on Monday began unveiling his 2020 budget, and the cycle of cuts, cancellation and rescue may repeat itself again. Indeed, his new budget proposes to cancel Wfirst as well as a pair of missions devoted to studying Earth’s climate, atmosphere and oceans.

“Scientists are going to have to work hard to make new friends in Congress,” wrote Matt Mountain, former director of the Space Telescope Science Institute, which runs the Hubble and will run the Webb telescope, and president of the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, in an email.

More practice in the art of the possible, Dr. Mountain said, “more stuff they never taught us at graduate school.”