Could Hydrogen Fuel Cells Revive, Threaten Battery Technology In Cars? – Forbes

The Hyundai Nexo fuel cell car Photographer: David Paul Morris/Bloomberg

© 2018 Bloomberg Finance LP

Autos with hydrogen fuel cells could eventually accelerate past battery powered ones because of their ability to provide environmentally friendly transport with almost unlimited green energy, zealots for the technology say, but there are some huge hurdles to jump over first.

Battery power looks to have won the race to replace the internal combustion engine (ICE) and its alleged carbon dioxide spewing threat to the planet. Tesla is in the fast lane, led by the Model3, with fuel cells stalled at the start line. But fuel cells’ inbuilt environmental advantage might give it victory, long term.

IHS Markit data suggests the battle is over, with its prediction that by 2032 battery electric vehicle (BEV) production will reach nearly 18 million a year, with fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEV) at less than 500,000.

And battery power does raise some environmental concerns. Mining for crucial metals like cobalt, lithium, nickel and copper can often raise concerns about worker and environmental safety. Recycling is a CO2 -inducing challenge, while heavier electric cars spew out more health threatening tire particles. In countries like Germany, where coal is often still used to generate electricity, the CO2 advantage doesn’t exist.

Agnostics say producing hydrogen by traditional methods uses up just as much carbon dioxide (CO2) as saved by the fuel cell process, and the renewable capacity from wind, solar and off-peak hydro-electric to provide enough material at a competitive price, simply doesn’t exist. And even if was, distribution and storage costs would be prohibitive, according to Professor Gautam Kalghatgi, visiting professor for Mechanical Engineering at Imperial College London, and Engineering Science at Oxford University.

Toyota Mirai (Photo by FREDERIC J. BROWN/AFP via Getty Images)

AFP via Getty Images

More aggressive cynics, like Tesla Inc’s Elon Musk, dismiss the idea as merely “fool’s cells not fuel cells” and “mind-bogglingly stupid”, but manufacturers are still investing large amounts in the technology, probably more as an insurance policy to guard against a rival surprisingly unlocking the key to its economic viability. Only last week, Mercedes parent and truck maker Daimler announced a deal with Volvo Trucks to share the costs of developing, producing and selling heavy-duty vehicles powered by fuel-cell technology. The declared aim was to have big, long-haul, fuel-cell powered trucks ready for market after 2025. But at the same time, Daimler said it was putting plans for a fuel-cell powered car on hold for a while. It had made a few GLC F-Cell models.

What advantages do hydrogen fuel cells have over batteries? Arval, part of the French bank BNP Paribas Group, lists these plusses and minuses.

· Faster refuelling compared with charging an electric car – 3 to 5 minutes just like a gasoline vehicle.

· No harmful emissions; only water.

· Impressive range of around 300 miles, on a par with conventional vehicles.

· Good efficiency levels; fuel cell powertrains are much more efficient at getting energy out of hydrogen than traditional cars are at getting energy out of gasoline or diesel.

It concedes that –

· Refuelling locations are sparse.

· Although the cost of fuelling a hydrogen car would be similar to traditional fuels, developing the technology isn’t cheap, nor is storing or moving hydrogen itself.

· And one it didn’t give – the electricity must be renewable otherwise there is no CO2 gain.

Mercedes-Benz GLC F-Cell, on hold until further notice Photographer: Alex Kraus/Bloomberg

© 2020 Bloomberg Finance LP

Meanwhile, news of a breakthrough in hydrogen on-board storage looked like mitigating a major problem with fuel-cells and cars, the huge cost of safe and adequate storage. The so-called ‘bath sponge’ technology was said to be able to hold and release large quantities of hydrogen at lower pressure and therefore less cost. The ‘bath sponge’ was developed by Northwestern University’s Professor Omar Farha.

BMW says various technologies will co-exist for some time yet, and hydrogen fuel cells could be the fourth option after gasoline, diesel, and battery-electric.

“The upper-end models in our X family (4x4s) would make particularly suitable candidates here,” former BMW R&D board member Klaus Froehlich said in a statement in March detailing the BMW i Hydrogen NEXT concept car. BMW has no plans yet to bring this car to market, saying the time is not yet right, nor the infrastructure in place.

“In our view, hydrogen as an energy carrier must first be produced in sufficient quantities at a competitive price using green electricity. Hydrogen will then be used primarily in applications that cannot be directly electrified, such as long-distance heavy duty transport,” Froehlich said.

BMW abandoned its original hydrogen plan, which used the gas to burn and power its gasoline engines. Now it has embraced the fuel cell, which produces electricity on board to power an electric motor.

BMW is also working with Toyota Motor on fuel cell technology and the Japanese company sells a few examples of the technology with its Mirai. Other FCEVs include the Honda Clarity and the Hyundai Nexo.

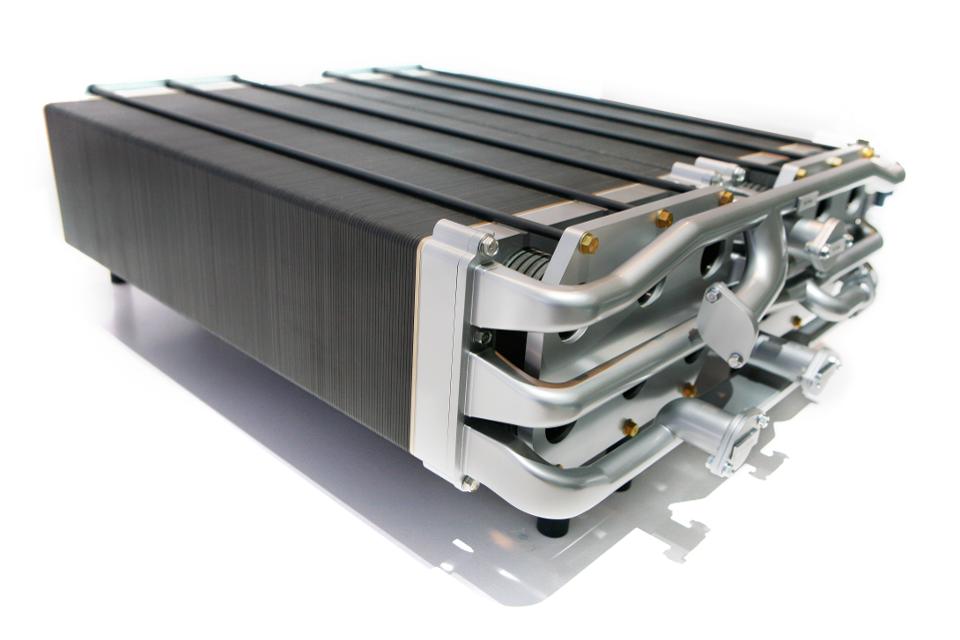

studio photo of a hydrogen fuel cell vehicle. This unit converts hydrogen gas into an electric … [+] current using a fuel cell process of recovering electrons. Its by products are electricity and water vapor.

Getty

Bloomberg New Energy Finance, in a recent report, pointed to the possibilities of hydrogen power, but said it would take a global government subsidy fund of $150 billion over 10 years to do it. You can assume the recent rapid onset of the coronavirus crisis will put that on hold for a year or two.

The European Union (EU) is pushing a hydrogen program, which will also be aimed at aviation and heavy industry. The EU’s CO2 legislation for cars and SUVs requires average fuel consumption the equivalent of 92 miles per U.S. gallon by 2030, so manufacturers would welcome the availability of an alternative CO2-free fuel. The EU regulations come close to demanding all new cars in 2030 are battery powered but so far electric cars have only reached successfully into high priced segments. The drive is on to build a mass market electric car by 2030, but forecasters predict this will fail. According to IHS Markit, global production of battery-only powered sedans and SUVs in 2030 will only reach 15.9% of the market, while gasoline, diesel and mild hybrids (internal combustion engines (ICE) boosted by additional electrification) will still be just over 70%. In a sane world, the EU should be nudging manufacturers to produce more efficient ICE vehicles. Instead it threatens to tighten the current rules.

Meanwhile U.S. investment researcher Energy & Capital reported that the Hydrogen Council, a global corporate outfit established to push the technology, reckons that by 2050, hydrogen will power more than 400 million cars and SUVs, up to 20 million trucks and 5 million buses. Hydrogen will provide 18% of the world’s energy.

Leading the charge for the adoption of fuel cells in Europe is David Wenger, general manager of Germany’s Wenger Engineering Gmbh, who organises regular seminars on the how fuel cells are inevitable.

Concept for a hydrogen household fuel cells. AA batteries with compartment filled with bubbling … [+] water. Versions with and without an electrical discharge in the water

Getty

Wenger said much investment has begun in the move to embrace hydrogen, with companies like Toyota and Hyundai leading the way and showing how the technology works.

“People are starting to wake up to the benefits of hydrogen as industry tries to fulfil obligations from the Paris Agreement on climate change and investors are moving in to help improve the product and lower costs,” Wenger said in a telephone interview.

The availability of hydrogen in Europe won’t be a problem using excess capacity from renewable wind-farm energy in Germany, Denmark, the Netherlands, Scotland and hydro-electric power in Switzerland, while the German chemical industry produces hydrogen which is just burned off as waste.

Why should car buyers go for fuel cells rather than battery electric?

“Battery power is not the solution for everything. Those that live in big cities for instance will find it very difficult to recharge electric cars. The move to hydrogen will be slow but sure, and by 2030 I would assume maybe 5% of cars and trucks in Germany would be fuel-cell powered,” Wenger said.

Professor Kalghatgi says hydrogen for transport is more of a niche development to exploit the excess renewable power which currently goes to waste.

Ventures like the Moroccan solar project won’t produce hydrogen cheaply enough and will be difficult to scale up. This project envisages uses huge solar power installations in the desert to produce renewable electricity devoted to producing hydrogen, which can then be shipped to customers in Europe.

A sign for EV and HYD cars to charge and fuel.

Getty

“Of course the main problem of hydrogen in transport is distribution and storage – how do you get it where the vehicles need it. An extremely expensive – 4 times the cost of a natural gas – has to be established,” Kalghatgi said in a email exchange with Forbes.

“This new announcement about better storage on the car in this “bath sponge” might help a bit to maintain the range of the car if it is commercially feasible but the production and distribution of hydrogen are the important issues,” he said.

“Of course, as electricity generation from wind and solar increases, there will be times when more electricity is generated than needed because of the intermittent nature of these renewables. This excess electricity can be used to generate hydrogen, rather than be stored in batteries etc, which can be used for transport if it can be delivered where it is needed. But I don’t expect such hydrogen to be anything but an extremely small fraction of transport energy demand for the foreseeable future,” Kalghatgi said.