Britain’s first astronaut shares her thoughts on confinement and isolation | Imperial News – Imperial College London

Helen Sharman shares what she learnt when living and working in space, and how those lessons could apply to isolation during the coronavirus outbreak.

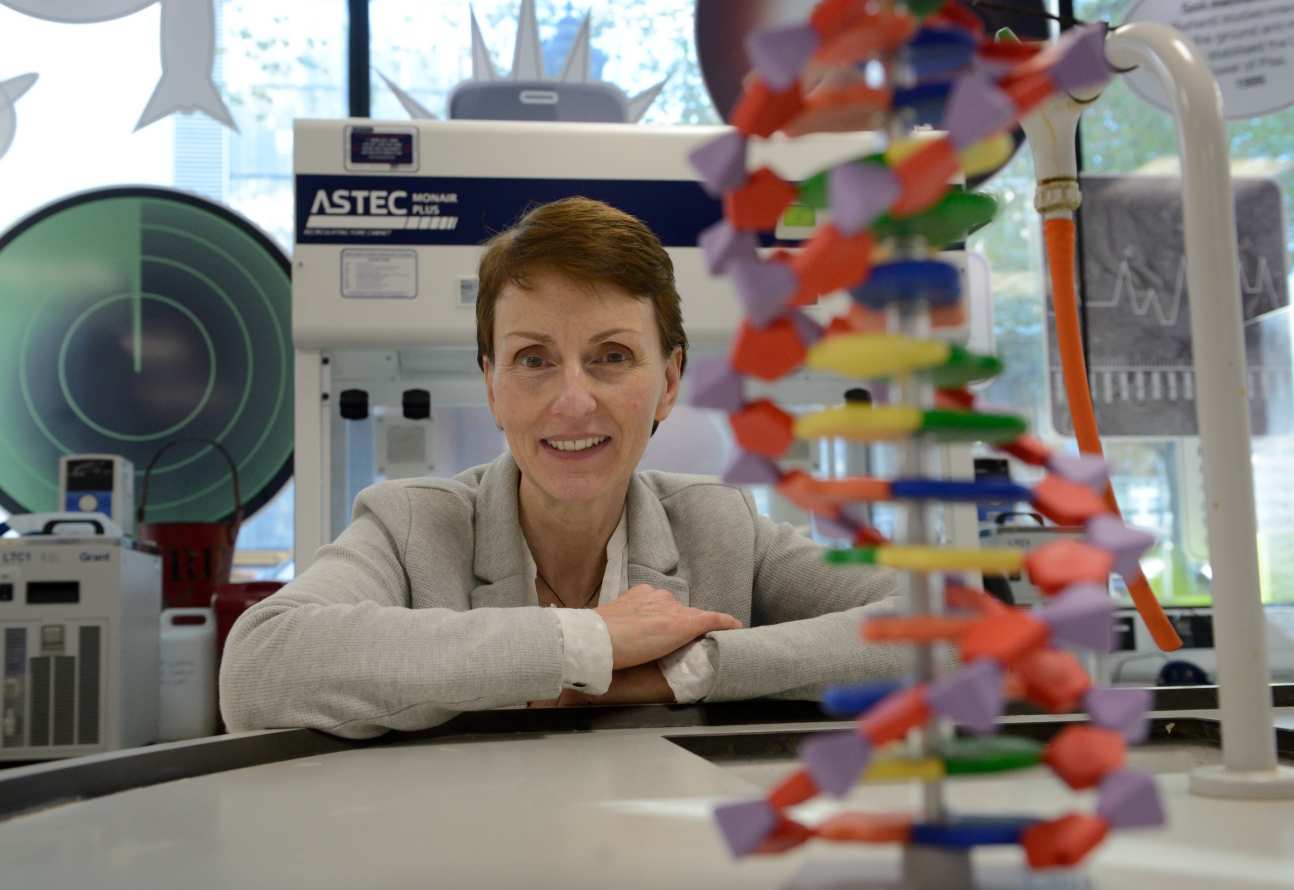

Helen Sharman became the first British astronaut in 1991 when she travelled to the Mir space station and undertook scientific research.

She now works with the Outreach team at Imperial, encouraging school children to take up science, maths and engineering.

Here she shares some of the things she learnt during her space mission about dealing with isolation and confinement.

“There are many ways we can maintain contact with people now”

In space, we have the basics for life of food and shelter and crewmates for company. However, what astronauts miss most is friends and family, those personal relationships that we often take for granted on Earth.

On long-duration missions, astronauts also miss the huge variety of people who we would usually meet in daily life on Earth, people who we interact with even if we don’t talk with them. I was in space before satellite phones were available to astronauts so I relied on the radio for contact with Earth and it was really good to be able to chat, albeit for only a few minutes (we were travelling over the Earth’s surface at 17,500 miles per hour so we were soon out of radio ‘sight’).

There are many ways we can maintain contact with people now: old fashioned phone, video chat, Skype, text, email, and so on; we can wave at neighbours, smile and say hello when we pass people two metres away in the street.

“We need to understand each other’s frustrations”

Living in a confined space with other people requires a bit more respect and tolerance than normal to maintain cordial relations. Astronauts do not select their own crew but the ability to cooperate and collaborate is a significant part of the selection process. As we don’t usually choose the people we share our homes with on this basis, we have to work particularly hard at open communication and active interactions.

We need to understand each other’s frustrations, what annoys us and what helps us to relax. And it helps if the grotty jobs are shared (tasks like compacting the solid toilet waste and changing air filters are done on rotation in space).

“Hard times shared can be a truly bonding experience”

Working as a team, my launch crew docked onto the space station manually because our automatic system failed. At the time of my spaceflight, a manual docking was something in which everyone in the crew had an active part (my task was to operate a periscopic camera so the commander could see where he was going). If we missed the space station by a mile, we could have a second attempt at docking but if we missed the docking port by a few centimetres, we could damage our spacecraft and the station sufficiently that we would all die.

We knew that we relied on each other for our lives. Having docked safely and opened the hatch into the station, I still remember that amazing feeling of togetherness as I hugged the cosmonauts who had been on board the station for the six months before my launch. Nearly thirty years on, my crew and I are still friends. Hard times shared can be a truly bonding experience.

“We still have some control”

Mission Control scheduled my days to the nearest minute. I did not mind because I knew it was the most efficient way to use my time. However, I did take pleasure in the small elements over which I could exert some control, like what sort of fruit juice I drank and when I went to sleep. Now, we have been told to stay at home but we still have some control (no one is telling us which book to read or what time to get up, after all) and there is a huge purpose: to save lives.

“I had plans and back-up systems”

I was not scared or anxious living with the risks of space travel because I had plans and back-up systems. I knew what to do in various emergency situations like loss of air pressure or a fire; I knew what to do in other non-standard situations like loss of radio contact or a manual docking.

For us now, it could be as simple as having a set of contacts in easy reach, a schedule for when you can access the home computer or a back-up plan of who will look after your pet if you are not able to that yourself for a while.

“We can make achievements every day that are useful”

When my space mission was in jeopardy part way through my training due to a lack of funding, I was asked if I would go into space just to become the first British astronaut, to do nothing other than float about and make a few broadcasts back to Earth. I said, “No!” because I wanted that spaceflight to be useful and I would rather let someone else be that astronaut in the future if that would be more worthwhile.

When my space mission was in jeopardy part way through my training due to a lack of funding, I was asked if I would go into space just to become the first British astronaut, to do nothing other than float about and make a few broadcasts back to Earth. I said, “No!” because I wanted that spaceflight to be useful and I would rather let someone else be that astronaut in the future if that would be more worthwhile.

And once in space, although it wasn’t particularly nice to be scheduled so precisely by Mission Control, I was grateful to have a busy working day because it made me feel useful. If suddenly our work diminishes and our days become less busy, we can feel at a loss.

However, if helpful, we can make our own daily schedules if they are not set for us, and if we are not working or volunteering, we can still have targets and make achievements every day that are useful.

“Plan something nice to look forward to”

With time to spare, we can do what we have always wanted to do but were previously too busy for. Astronauts on long-duration missions enjoy catching up with films and books, for instance. On Earth, even just at home, we have a whole load of activity to choose from. And we can plan something nice to look forward to because this will not last forever.

“We have the time to stop and enjoy things”

One of the things my crew and I loved to do at the end of the working day in space was to look out of the window. As we orbited Earth, the planet rotated below so the view was constantly changing. I was entranced with how the sun reflected off lakes on Earth. Seeing lights in cities appear as we entered dusk was magical. Sunrise was spectacular, as the atmosphere brightened and the colours morphed from yellow to pale blue, going from pitch black to brilliant light in a few seconds. Snow, deserts, oceans and clouds were all beautiful.

One of the things my crew and I loved to do at the end of the working day in space was to look out of the window. As we orbited Earth, the planet rotated below so the view was constantly changing. I was entranced with how the sun reflected off lakes on Earth. Seeing lights in cities appear as we entered dusk was magical. Sunrise was spectacular, as the atmosphere brightened and the colours morphed from yellow to pale blue, going from pitch black to brilliant light in a few seconds. Snow, deserts, oceans and clouds were all beautiful.

But I could not experience weather and fresh air in space. Now, we have the time to stop and enjoy things like listening to birdsong, seeing how the sunlight moves across a building over the course of a day and how this changes depending on the time of year, appreciating the beauty in clouds and smelling the outside air as we open a window (I couldn’t do that in space!)

“When the pandemic is over, the world will be a better place to live in”

During my entire space mission, I did not once think about possessions, the objects that we often strive to own, perhaps to show off our wealth and identity. Back on Earth and confronted by materialism, I downgraded the relative value of ‘stuff’ in my life and I think COVID-19 will have a similar effect on many of us.

Being less of a consumer society will benefit the environment and reserve resources for what we really need, but I think we will feel the change in society that will be more communal, more cohesive and generally nicer. When the pandemic is over, the world will be a better place to live in.

Watch the video below to see how Helen is structuring her days in isolation.