Boeing’s Fall From Space – Seeking Alpha

Space is a rapidly growing sector, and Boeing (NYSE: BA) was one of the first players to enter it, having been working to develop a crew capsule to launch astronauts to the international space station (“ISS”) . The capsule, named Starliner, was originally meant to fly . It’s been some time since that deadline came and went, but with SpaceX (SPACE), their only competitor for this task, also failing to meet the deadline, Boeing was never too far behind. Or so it seemed. Unfortunately, being one of the first movers doesn’t guarantee success. This article will uncover the struggles Boeing has faced when developing their Starliner capsule and then broaden the discussion to Boeing’s greater space endeavors. From here, I will analyze the overall impact that Boeing’s faltering space business will have on the company as a whole.

Current Issues

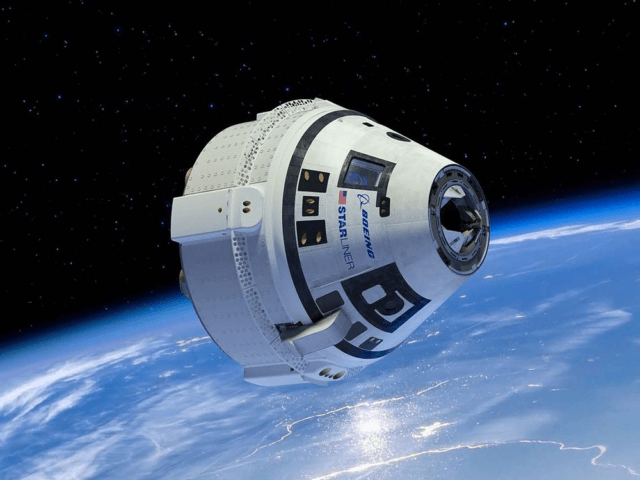

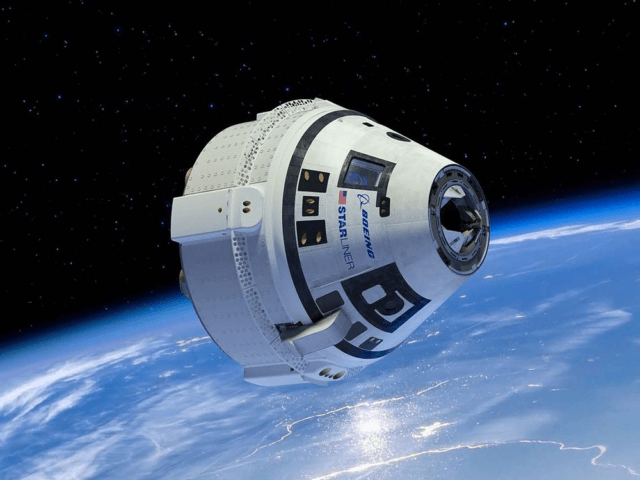

The Starliner, originally called the CST-100 and pictured below, might be experiencing its greatest challenge to date. Back in 2018, the capsule suffered a propellant leak during a test of the emergency abort engines, which delayed the program by and up to seven (based on changes in flight schedules [,]). While this was quite a big issue at the time, Boeing knew what was wrong with its capsule and was able to fix it in time. Now, Boeing is facing a different problem.

Source:

Shortly after the Starliner detached from the Atlas V rocket carrying it into orbit, it became evident that . This particular issue isn’t too large, but much more concerning is even almost two months after the mission’s completion. This is concerning because, even if it were difficult to fix, at least the company could begin work to fix it. Not knowing what the source of the issue means that not only will it take time to fix the issue, it’s going to take time to identify it as well. As Doug Loverro, NASA’s associate administrator for human exploration and operations, “We don’t know how many software errors we have. “We don’t know if we have just two or we have many hundreds.” also found that the ground station experienced difficulty communicating with the capsule, another issue that needs to be remedied.

. However, , “I just don’t think we have enough information at this point, we’d be very premature to make any announcements regarding that.” The possibility of a second flight test would mean further delays for Boeing and due to NASA’s strict safety requirements, I believe it to be quite likely. Even without another test flight, these failures will require significant time to remedy and pass inspection.

NASA will also begin a workplace culture investigation, as concerns that were intentionally covered-up, . If this isn’t the case, the review process will still take some time and raise concerns about why the issues weren’t uncovered during pre-flight testing. To cite the 737 MAX again, locating and fixing a software problem can be a very time-consuming process, taking , as . A discussion of when I believe the Starliner capsule will see its first crewed flight will be continued in the ‘competition’ section.

Boeing’s Launch Vehicles

The failures of Boeing’s crew capsule are representative of their greater failures as a space-bound company. , a spaceplane hoping to launch small satellite payloads of up to 3,000 pounds for just $5 million with rapid reusability, is just another example of these struggles. Beyond their failed spaceplane and struggling Starliner capsule, Boeing also operates the United Launch Alliance (“ULA”) through a joint venture with Lockheed Martin (NYSE: LMT). , the Atlas V, Delta IV, Delta II, and Vulcan Centaur. Each rocket serves a different purpose, , starting at $109 million per launch, can lift up to 41,570 pounds into low earth orbit (“LEO”) and is touted as their most reliable rocket. The Delta IV, starting at and , can lift 62,540 pounds into LEO and 25,290 pounds into LEO for their heavy and medium-lift variants respectively. The Delta II, starting at , has . A discussion of competition later in the article demonstrates just how far behind ULA is in the launching industry.

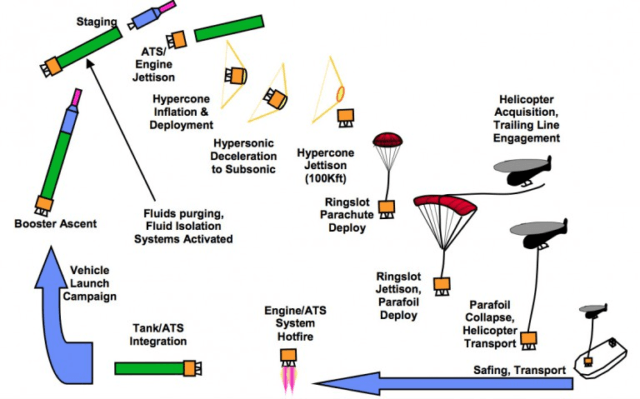

The Vulcan Centaur has some more information to cover, as the first new rocket ULA has brought into service . Born from (BORGN) to develop a new rocket engine in 2014, Vulcan Centaur has been making steady progress towards service. and the development of the rest of the rocket is in ULA’s hands. One of the most interesting aspects of the rocket is its recovery process. ULA is designing the rocket to be fully reusable, a move that would slash the launch costs, but not in the way SpaceX and Blue Origin are doing it. Instead of a propulsive landing, ULA is developing a system that they’ve coined as . The plan behind SMART Reuse, or Sensible Modular Autonomous Return Technology, is to recover the engines of their main booster via a helicopter. Upon first glance, this may seem a bit insane, but it actually makes a whole lot of sense. It’s certainly easier to develop than propulsive landing and catching objects falling from orbit relying on a helicopter and parachutes has . Because of this, I don’t anticipate that ULA will have much trouble perfecting this technique and do believe that they will ultimately be successful in their endeavors. In terms of when this rocket will enter service, and by the year’s close, I believe that they will ultimately be successful. However, , a year later than ULA originally anticipated due to other developmental delays.

Source:

However, the most important question still remains — will ULA’s cost-cutting efforts be successful? ULA CEO and President, Tory Bruno, that “This will take up to 90 percent of the propulsion cost out of the booster.” This is due to the fact that the weight of the engines will be shedded once they’ve accomplished their task and therefore lightens the rocket over time. However, and it is also worth noting that propulsive landing also allows rockets to shed some weight. Beyond propellant cost, , meaning reusability of these engines is a much more important aspect of bringing down the cost. By bringing their cost down to with the capabilities to deliver , ULA hopes that their Vulcan Centaur will be the future of their launch business. Unfortunately, this cost isn’t representative of this maximum launch capability. The rocket is meant to be able to be heavily modular, with the ability to add boosters for greater required thrust. $82 million is ULA’s goal for their bare-bones rocket, while 76,900 pounds into LEO requires a fully-loaded rocket. Unfortunately, these are the only two points available and the cost of their fully-loaded rocket is unknown, just as the launch capabilities of the bare-bones rocket is unknown.

Competition

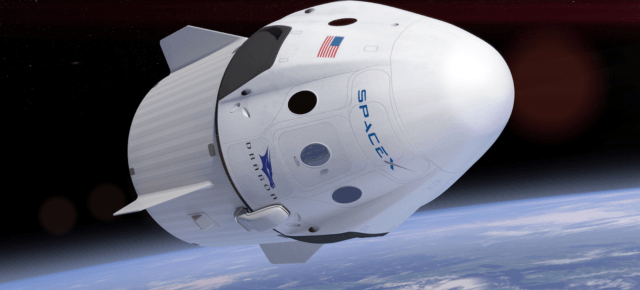

For crewed launches to the ISS, SpaceX is Boeing’s greatest, , competitor. Having , SpaceX is far ahead of Boeing which doesn’t plan to demonstrate such capabilities and . , though the launch escape demonstration is more challenging as it requires the capsule to separate from the rocket while it is in flight. By bypassing this test, Boeing will likely be subject to more strict testing and approval of its abort systems before flying astronauts. SpaceX’s recent hiring of former NASA chief of human spaceflight, William Gerstenmaier, is another bonus for NASA’s confidence in SpaceX’s safety capabilities. For their first crewed launch, , which was seemingly confirmed by SpaceX senior advisor and former NASA astronaut, Garrett Reisman, during (1:18:00). However, indicate that SpaceX is aiming to launch its first crewed mission around May 7. The date is subject to be moved either slightly later or earlier based on when NASA wishes to end the service of the astronauts currently in the ISS. While Boeing still hasn’t released any ballpark estimates for their launch date, I wouldn’t expect to see a crewed Starliner launch until the second quarter of 2021. This is mostly due to the extensive work that still needs to be done with the capsule, especially with software. indicating that NASA may decide to extend the Crew Dragon’s mission from weeks to months further demonstrate that NASA doesn’t anticipate Boeing’s capsule to be ready soon.

Source:

Beyond a faster development timeline, SpaceX is offering a more competitive package than Boeing in terms of cost. The Starliner will ride atop an Atlas V rocket, which, as I’ve already mentioned, costs $109 million per launch. Dragon’s launch vehicle, , costs just $62 million and can lift up to 50,265 pounds into LEO, though the payload comparison doesn’t really apply here. SpaceX’s propulsive landing allows the company to recover their engines, as well as the rest of their first stage, creating significantly greater cost savings than ULA’s SMART Reuse which just captures the engines. Because of this, NASA will be forced to . After the are completed, it seems unreasonable to expect NASA to choose Boeing for future launches due to the significantly higher cost and will instead rely on SpaceX. This decision would ultimately kill Boeing’s crewed launches for NASA. Additionally, will also be able to undercut . While likely to be a small portion of their sales due to the , it still represents yet another area where Boeing’s space endeavors are to be thwarted by SpaceX.

Without their spaceplane, Boeing’s only launch vehicles lay with ULA. Unfortunately, ULA’s rockets are quickly becoming obsolete. I’ve already discussed the pricing of their rockets compared to the reusable Falcon rocket, but the Falcon isn’t alone in its dramatically lower launch costs. SpaceX also currently operates , a $90 million launch vehicle that can lift up to 140,660 pounds into LEO, almost double what the Vulcan Centaur is hoping to achieve and close to the price of its cheapest variant. SpaceX’s heavy-lift rocket would be ULA’s second cheapest rocket and the Falcon 9 costs the same as the cheapest ULA rocket, Delta II, which has a launch capacity of almost half of the Falcon 9. Even more damning for ULA, is SpaceX’s Starship.

The Starship is SpaceX’s own new rocket in development, which SpaceX anticipates to be able to carry to any orbit, made possible by , and eventually cost . Even ignoring the lift capacity, the low cost is incredibly impressive and far below the costs of any other orbital rocket. SpaceX believes they can accomplish this low cost with 100% reusability of the rocket and booster and $900,000 in fuel costs. Currently, SpaceX’s first stage is 100% reusable, but they don’t reuse their second stage, as is the case with all other reusable rockets (including the upcoming Vulcan). By making their second stage reusable as well, SpaceX now has a fully reusable spaceship. SpaceX is targeting its first orbital flight of Starship for and anticipates commercial launches , on par with the Vulcan Centaur (though reusability will be a given from the start) with a fully crewed launch around the moon . In short, not only is this booster better than every other rocket on the market in terms of price and weight capacity, its development is moving faster than ULA’s Vulcan Centaur. Essentially, Starship is making ULA’s next big thing obsolete before it even begins its service.

Blue Origin, owned by Amazon (NASDAQ: AMZN) founder Jeff Bezos, is another competitor for ULA and is, again, offering better value. Currently, but is working to bring one into service. will use the aforementioned boosters in development by Blue Origin for ULA, which the company hopes will allow the rocket to carry 99,208 pounds into LEO beginning in 2021. In terms of cost, Blue Origin hasn’t released anything but says on that their reusable first stage, employing a comparable tactic to SpaceX, will allow them to make New Glenn a “cost-competitive system”. The choice by SpaceX and Blue Origin to develop a propulsive landing system likely cost significantly more upfront due to the various technical challenges, but will allow for greater cost reductions in the future. Simply put, ULA is outdated and can’t compete with the cheaper, more powerful, rockets from SpaceX and Blue Origin.

involves a moon lander for . At this stage, little is known about the proposed lander, but . These companies are , Blue Origin, and Dynetics, though Blue Origin is partnering with Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman (NYSE: NOC), and Draper Laboratory to develop their lander and Dynetics is working with Sierra Nevada Corporation. Very little is known about any of the proposals and only Blue Origin has . Even so, there is quite little information available on the lander. All we can do now is speculate about who will ultimately win the contract, but due to how little is known, I feel that it is too early to determine this, though I do feel that Blue Origin has the greatest advantage here due to their strong partners and their . As a result of strong competition, I believe that Boeing’s multiple space endeavors will fail to generate any meaningful business for the company.

Company Impact

Boeing spent $758 million in research and development (“R&D”) on ‘Defense, Space & Security’ in , 23.5% of their total R&D spending on the year. The year prior saw a similar proportion, with a total of $788 million spent on the R&D of Defense, Space & Security, making up 24.1% of Boeing’s total R&D spending. For both of those years, 2018 and 2019, their total profit in the sector was $771 and $51 million respectively, (the latter’s weak profit was attributed to shortcomings in the Commercial Crew Program) meaning that Boeing is currently operating this sector at a loss. While it isn’t immediately apparent how much of this spending goes towards Boeing’s space endeavors, versus defense or security, it seems logical to assume that a large portion of the spending is commanded by space development. I am confident in this assumption because, although receiving a number of grants from the US government, at the end of 2018. Government funding, as of the end of 2018, totaled $1.2 billion, implying a total project cost of around $4.8 and funding by ULA of $3.6 billion at that time. Though, as ULA is a joint venture, Boeing had likely contributed around $1.8 billion. Again, this is just as of October 2018, since then the rocket has seen even greater development. This makes Vulcan Centaur alone, quite a costly piece of the company’s R&D, not to mention the other rockets that Boeing is working to develop and past projects, such as the Phantom Express, that have been scrapped. As a result, I suspect that space commands around 50%, or $398 million, of Boeing’s Defense, Space & Security R&D expenditures and therefore 12.1% of Boeing’s total R&D expenditures.

It’s also safe to assume that the majority of Boeing’s profit from their Defense, Space & Security sector is not made up of their space business. , back when they broke down the sector into more specifics, demonstrates that, in fact, just 19.4% of the sector’s earnings come from space. Applying a 20% margin to Boeing’s Defense, Space & Security sector would mean a profit of $154.2 million in 2018 for Boeing’s space business. I’m going to exclude 2019 in this discussion because it is an anomaly. In terms of the company’s total profit, this represents just 1.5%. So, while making up 12.1% of the company’s R&D budget, the business is responsible for only 1.5% of the company’s total profit — a clear discrepancy. Essentially, Boeing is spending lots of money on a business that doesn’t have much of a future. Without such a future, continued investments seem to be in vain and continuing this pattern will weigh heavily on Boeing’s finances. And Boeing’s finances aren’t doing too great right now. Working with negative cash flow on the year () for the first time , the company needs to regain its mojo and continuing to spend money on a business that is not, and likely will not, provide a return on investment is not the way to do that.

Boeing has seen a pretty great fall from grace in the past year. The king of the skies that is . This debacle has been pretty heavily covered by the media, but Boeing’s space woes have seen much less coverage and with the weight these blunders can have on the company, it seems odd. I suppose that when people think of Boeing, they don’t tend to think of their space endeavors. However, and had they been successful, Boeing could’ve been a leader. However, through the course of this article, I have demonstrated why Boeing doesn’t have a future in space. At this point, Boeing has two options. The first is to slowly begin divesting from space exploration and maintain their other operations. A company with stressed finances needs to cut costs and the best areas to cut those costs is where the cash is being burned. The second is to do the opposite and commit a large sum of cash in order to make their space program competitive. Either option is expensive and, though the first entails less risk, working to make their program successful could ultimately be a profitable investment due to the rapid growth of the industry. However, I just don’t believe that Boeing is in the position to invest what is needed in order to accomplish this task. What is most likely to happen is neither of these options. Boeing will likely continue to spend as they have been for years on their space business, without ever giving it enough of an appeal over its competition to generate a return on investment.

Disclosure: I/we have no positions in any stocks mentioned, and no plans to initiate any positions within the next 72 hours. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.