Best Image Yet of the Cosmic Web – SkyandTelescope.com

Using the light cast by galaxies bursting with new stars, astronomers have mapped out a piece of the cosmic web 12 billion light-years from Earth.

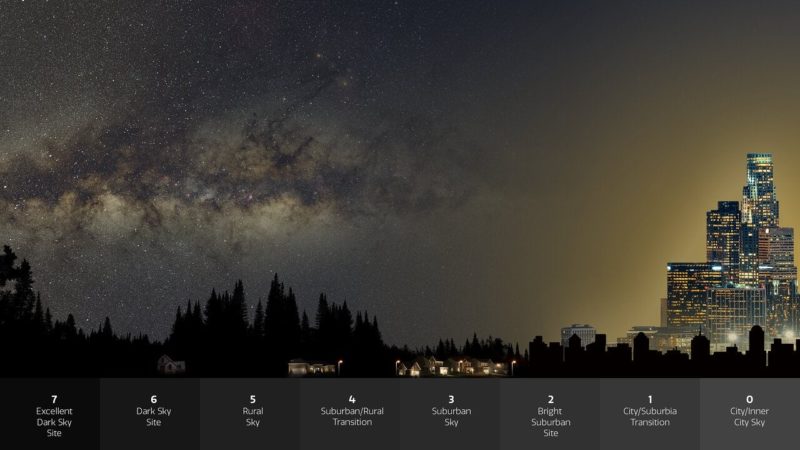

Simulations show that a cosmic web of gaseous filaments, separated by large voids, fills the universe.

Springel & others / Virgo Consortium

Gravity has woven the universe into a cosmic web. Primordial gas that filled the young cosmos collapsed into expansive sheets, then into filaments, separated by huge voids. On very large scales, this gas has a texture like soap bubbles or tangled spiderwebs.

But even though computer simulations first revealed this large-scale structure decades ago, it’s difficult to picture — literally. We can easily see the light from galaxies and galaxy clusters, but the sparse gas bridging from one cluster to another has largely evaded detection.

With cutting-edge ground-based instruments, that’s changing. In the October 3rd Science, Hideki Umehata (RIKEN Cluster for Pioneering Research and University of Tokyo) and colleagues report an image of the cosmic web when the universe was only 2 billion years old. Sure, it’s fuzzy, but it’s also the best view we’ve got!

Lighting Up the Web

The blue fuzz to the left of the quasar UM 287 (white dot in center) is a filament of hydrogen gas extending 1.5 million light-years long.

S. Cantalupo / UCSC

Astronomers know the cosmic web exists because they’ve detected it indirectly. If you look through the cosmic web at a brilliant source in the distance, the source’s light will show a “forest” of hydrogen absorption lines from all the filaments it intercepted along the way.

But there aren’t that many bright, distant sources out there. And the gas in between galaxies is so spread out it doesn’t emit much light itself.

Unless, that is, the gas is lit up by galactic flashlights. Galaxies bursting with newborn stars or hosting a gas-guzzling black hole will light up their surroundings, irradiating the sparse hydrogen gas that surrounds them.

This has been done before — the galaxy UM 287 acts as a cosmic flashlight to light up a 1.5 million light-years-long filament. But now Umehata and colleagues have imaged the same thing on an even bigger scale.

A Set of Cosmic Flashlights

Using the Multi Unit Spectroscopic Explorer (MUSE) on the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope in Chile, Umehata’s team zeroed in on a distant collection of galaxies, collectively known as SSA22, whose light takes 12 billion light-years to travel to Earth. The galaxies themselves are brilliant with newborn stars, black hole activity, or both. The light pouring out of these galaxies lights up the gas between the galaxies, boosting its emission.

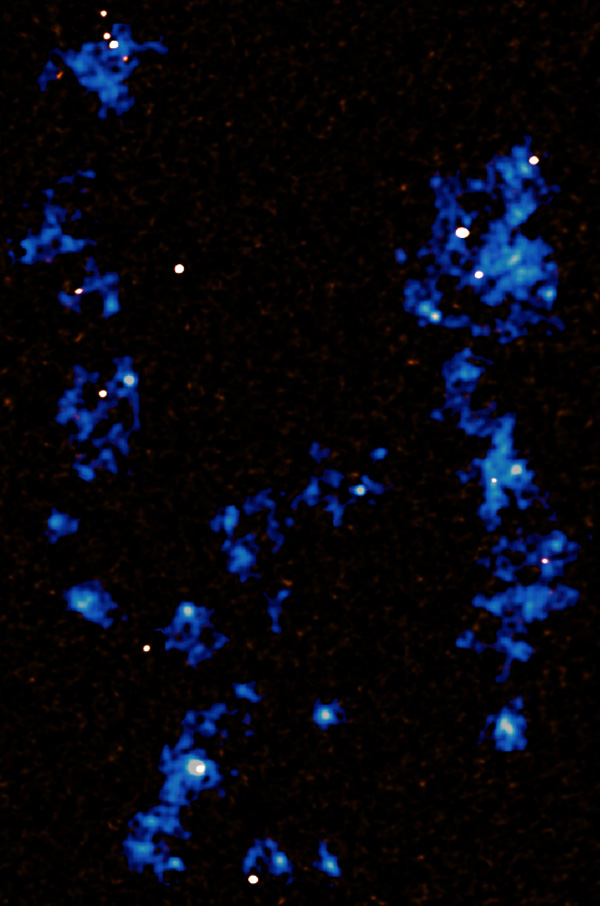

Two filaments, each about 3 million light-years long, run vertically through this image, taken by the MUSE instrument on the Very Large Telescope. The white dots are galaxies bursting with new stars, imaged by the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array in Chile. (Other galaxies with gas-guzzling black holes at their centers, imaged by NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory, are not shown here.) The 24 galaxies associated with this group are embedded in the hydrogen-gas filaments.

Hideki Umehata

MUSE detected bright patches emitted by hydrogen gas around the galaxies (this is gas that is bound to the galaxies), as well as fainter patches that connect the galaxies. Most of the fainter emission comes from two filaments that run vertically through the image, extending some 3 million light-years. (We’re seeing this length projected onto the two-dimensional plane, so the total extent could be even longer than that.)

The astronomers calculate that this region of cosmic web contains a trillion Suns’ worth of gas. Moreover, this gas doesn’t stay still. This gas is likely trickling down onto the galaxies, fueling their star formation and black hole activity.

“The observations from Umehata et al. are just the tip of the iceberg,” says Erika Hamden (University of Arizona), who authored an accompanying opinion piece in Science. “Other similarly bright structures will eventually be identified and observed.”

Ironically, though, observations of the cosmic web will — for now — remain limited to the distant, early universe. Light at ultraviolet wavelengths will stretch into visible and even infrared wavelengths as it passes through the expanding universe. To observe the cosmic web nearby, we would need access to ultraviolet wavelengths that are blocked by Earth’s atmosphere.

“Probing the full history of the universe by observing gas emissions requires a probe-class UV satellite,” Hamden adds. “It requires getting a large UV telescope into space, which is challenging for logistical and financial reasons.”