Astronomers See Extreme Photons from Collapsing Massive Stars – Sky & Telescope

Astronomers have detected a long-sought signal from gamma-ray bursts — the highest-energy photons ever seen from these events.

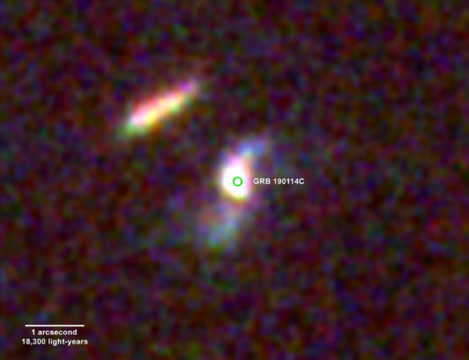

Gamma-ray bursts are the most powerful explosions in the Universe. They emit most of their energy in gamma rays, light which is much more energetic than the visible light we can see with our eyes. Hubble’s observations suggest that this particular burst displayed such powerful emission because the collapsing star was sitting in a very dense environment, right in the middle of a bright galaxy 5 billion light years away.

ESA / Hubble / M. Kornmesser

On January 14, 2019, two space telescopes caught a flash of gamma rays, the signal of a massive star that had just collapsed into a black hole. This powerful explosion released more energy in a second than the Sun would emit over its entire lifetime. Although rare in any given galaxy, such events are common across the universe — astronomers detect new long-duration gamma-ray bursts every day. But what happened next was exceedingly rare.

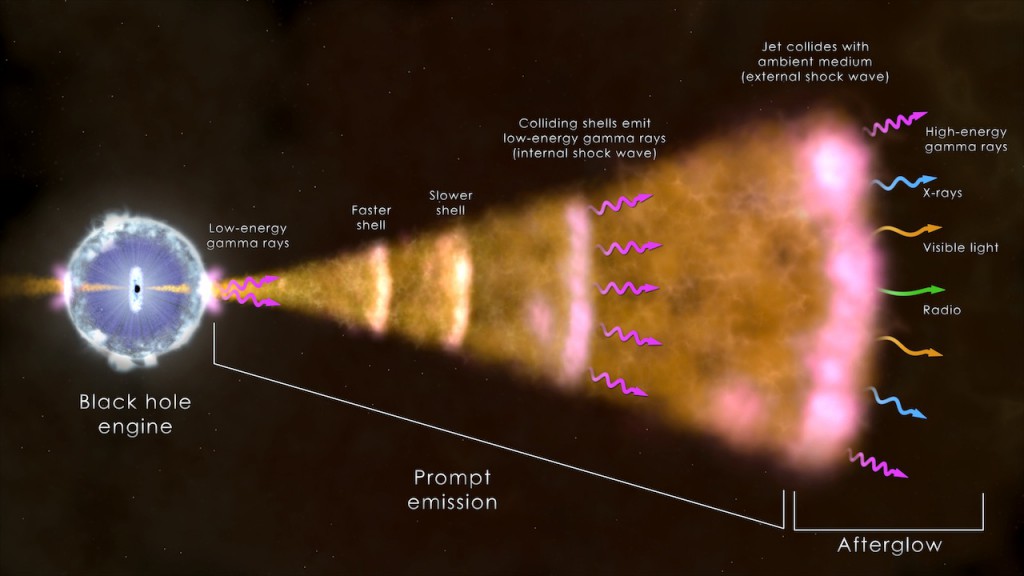

In a matter of moments, the outer layers of the star had transformed into a swirling disk, delivering gas to the gaping maw that now sat at its core. Twin jets of material sprang from opposite sides of the disk, traveling at more than 99.999% of the speed of light — only to ram into surrounding material. Within seconds, that material was aglow, a shining echo of the star’s collapse. And within a minute, from within this afterglow, a shower of powerful gamma rays emerged, more energetic than any recorded from such a burst.

These photons, with energies around 10 million times higher than the highest-energy X-rays, rained down above the twin Major Atmospheric Gamma Imaging Cherenkov (MAGIC) telescopes in La Palma, Spain, for 20 minutes. MAGIC is an unusual telescope in that it doesn’t detect gamma-rays themselves, which never make it through Earth’s atmosphere. Instead it makes indirect detections of the showers of particles that every impacting gamma ray creates.

The large central H.E.S.S. telescope is shown, as well as two of the array’s four smaller telescopes.

MPIK / Christian Föhr

Another telescope, the High-Energy Stereoscopic System (HESS) in Namibia, does the same and found only slightly less energetic photons from an earlier event in 2018.

A series of papers in the November 20th Nature dissect the observations of these two bursts and what they mean for how the most massive stars end their lives.

Expecting the Unexpected

Astronomers have been studying gamma-ray bursts for more than 50 years, ever since their detection by military satellites in the late 1960s. This is the first time they’ve detected photons with such high energies, technically in the tera-electron volt range — but the discovery wasn’t unexpected.

Emission from gamma-ray bursts comes in two flavors — there’s the immediate radiation from the jets coming from the vicinity of the collapsed black hole, and then there’s the afterglow, created when the jets hit the stuff around the star and set it alight. In both stages, most of the photons were thought to come from speedy electrons whirling around magnetic field lines. If there are enough electrons, though, it’s likely that they’ll bump into newly created photons, boosting their energy.

The usual picture for GRBs has initial gamma rays coming from within twin jets of material (only one of which is shown here). The afterglow, arises when the jet rams into the cocoon of hot gas surrounding the imploded star.

NASA Goddard

Astronomers had long predicted the phenomenon in gamma-ray bursts — it’s just it took them a long time to actually see it. “This very high energy emission had been previously predicted in theoretical studies but never before directly observed,” said Alexander van der Horst (George Washington University).

What Makes These GRBs Special?

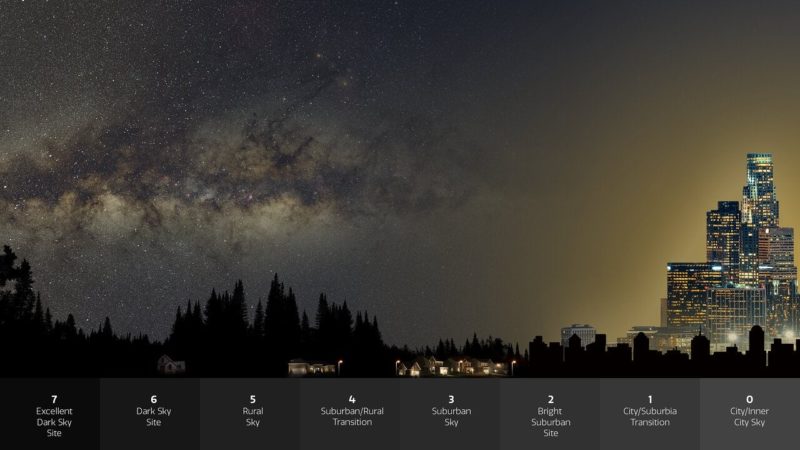

To detect these high-energy photons, a burst must be bright, so that it’s throwing off enough photons for us to detect. It must also be relatively local. Gamma rays from sources in the far-off universe will interact with stray visible-wavelength photons on their way toward Earth, disappearing in a spontaneous act of particle creation. So, for rare high-energy photons to survive long enough to be recorded, it helps if they start out nearby.

The 2019 burst, designated GRB 1901114C, traveled 4.5 billion years to reach Earth, which (amazingly enough) makes it one of the nearer gamma-ray bursts. But it’s not exceptionally bright. Nevertheless, it was one of the first gamma-ray bursts to be detected at such high energies — the previous decade of observations with both the MAGIC and HESS Telescopes had turned up no solid detections of super high-energy gamma rays from other bursts.

One of the studies appearing in Nature attributes the find to “a favorable combination of its low redshift [that is, distance] and suitable observing conditions.” However, another study to appear in Astronomy & Astrophysics reports observations from the Hubble Space Telescope, the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), and the Very Large Telescope, making the case that GRB 1901114C is special after all.

The fading afterglow of GRB 190114C and its home galaxy were imaged by the Hubble Space Telescope on Feb. 11 and March 12, 2019. The difference between these images reveals a faint, short-lived glow (center of the green circle) located about 800 light-years from the galaxy’s core. Blue colors beyond the core signal the presence of hot, young stars, indicating that this is a star-forming spiral galaxy. Its light has traveled about 4.5 billion years to Earth from the direction of the constellation Fornax.

NASA / ESA / V. Acciari et al. 2019

“Hubble’s observations suggest that this particular burst was sitting in a very dense environment, right in the middle of a bright galaxy,” explained team member Andrew Levan (Radboud University, The Netherlands). “This is really unusual and suggests that this concentrated location might be why it produced this exceptionally powerful light.”

As the internationally based Cherenkov Telescope Array and the Large High Altitude Air Shower Observatory in China come online in the next few years, perhaps such detections of extreme-energy photons will become routine. If they do, these photons will shed light on the conditions within these extreme environments.