Astronomers Find 8 Repeating Radio Bursts From Deep Space – ExtremeTech

This site may earn affiliate commissions from the links on this page. Terms of use.

The universe is rife with mysteries, but few are as perplexing as fast radio bursts (FRBs). These distant, highly energetic radio-frequency flashes were only discovered in 2007, and most observations have come from non-repeating sources. That makes it hard to study the phenomenon in detail. Astronomers knew of just a few repeating signals before, but a team of researchers reports the discovery of eight more repeating FRBs that could help us understand what’s going on out there.

The first recorded FRBs happened in 2001, but no one spotted it in the data until a review in 2007. As the name implies, fast radio bursts last just a millisecond, and the signal here on Earth is minute — it’s similar to a cell phone calling from the moon. However, the sources are incredibly intense to be visible on Earth at all. Astronomers estimate the average FRB releases as much energy in a millisecond as the sun puts out in 80 years.

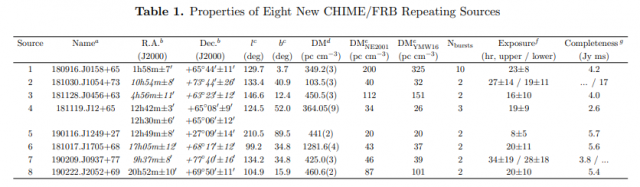

While dozens of FRBs have cropped up in the data since that first signal, there’s only been a handful of repeating sources. The first of these is known as FRB 121102. It was alone until earlier this year when astronomers found two more repeating FRBs. The new study (available on the preprint arXiv service) from McGill University points to eight more repeating FRBs.

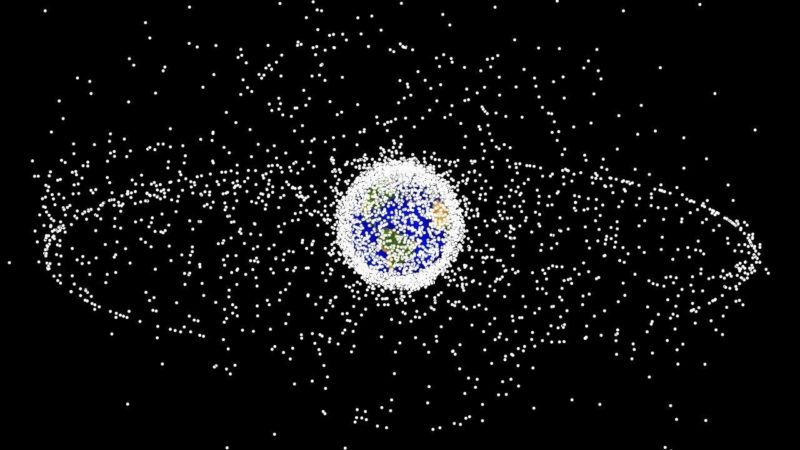

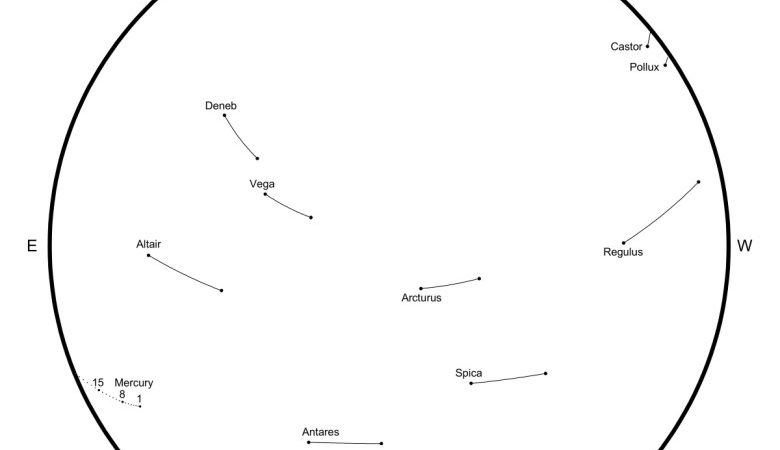

The researchers used the Canadian Hydrogen Intensity Mapping Experiment radio telescope (above) to search for FRBs. They observed six new FRBs that repeated just once, and another that fired off three bursts. The last one has scientists particularly excited. Currently called FRB 180916.J0158+65, this source released ten fast radio bursts during four months of observations.

It has been suggested that all FRBs might actually be repeating, but the time between flashes varies hugely. One of the newly identified repeaters flashes every few days, but other sources may go years between signals. To help unravel this mess, the McGill University team compared the new repeaters to non-repeating FRB signals. They found the repeaters and singles have similar “dispersion measures,” which describes the way the signal stretches as it travels across the universe. However, bursts from repeaters tend to be a few milliseconds longer than singles, and they sometimes release smaller sub-bursts after the main one.

Knowing where FRBs will happen helps scientists get instruments pointed in the right direction to collect as much data as possible. The dominant hypotheses suggest FRB mechanisms like energetic supernovae and emissions from magnetized neutron stars known as magnetars, but no one knows for sure. With more confirmed repeating FRB sources, we may finally be closing in on an answer.

Now read: