Arrival of interstellar object, comet 2I/Borisov, excites astronomers partly because of how familiar it is – ABC News

A dirty snowball or snowy dirtball (depending on which astronomer you’re talking to) is hurtling towards the Earth at approximately 33 kilometres per second.

It’s making astronomers across the globe very excited, because this isn’t just any comet we’ve detected — it’s a comet from outside our solar system.

“Having an interstellar object around is the most incredibly exciting thing,” said astronomer Michele Bannister of Queen’s University Belfast.

Here are some of the reasons 2I/Borisov has got stargazing scientists so excited.

Borisov is only the second interstellar object we’ve detected

The comet has been dubbed Borisov after the amateur astronomer Gennady Borisov who first detected it on August 30 this year.

The 2I in the comet’s name stands for second interstellar, meaning it’s the second interstellar object we’ve picked up entering the solar system.

The first was a mysterious cigar-shaped object dubbed ‘Oumuamua, a Hawaiian word meaning “a messenger from afar arriving first”, that visited us in 2017.

We know Borisov is an interstellar interloper because of the hyperbolic shape of its orbit, which indicates it’s not gravitationally bound to the Sun, and the fast speed at which it is travelling.

“These things are sleeting through the solar system all the time, it’s just we’ve finally got to the point where our technology can catch them,” said astronomer Jonti Horner of the University of Southern Queensland.

“It would be foolish to imagine we’re the only planetary system out there that’s spitting things out into space, that’s littering the cosmos.”

That’s because objects like Borisov and ‘Oumuamua are a natural outcome of how planetary systems form and evolve, said Dr Bannister.

“Any given planetary system over its lifetime will eject trillions on trillions of these little worlds into the cosmos, and they just wander between the stars,” she said.

We spotted Borisov a lot earlier than ‘Oumuamua

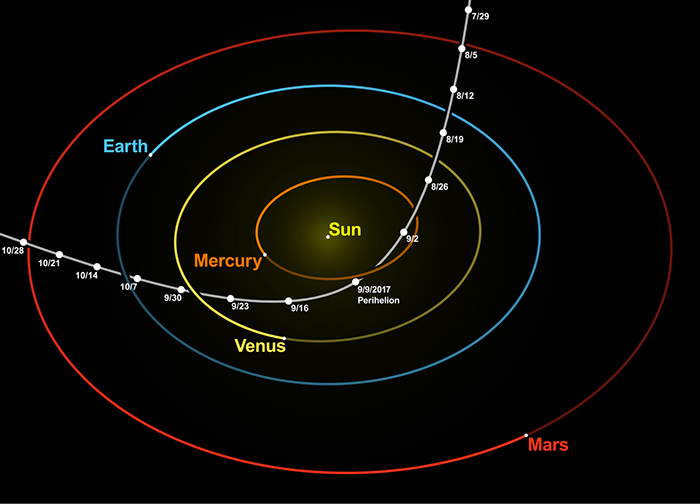

External Link: Click to play: The trajectory of C/2019 Q4, now renamed 2I/Borisov. (Courtesy: NASA/JPL-Caltech)

There are a few reasons why we’ve been able to pick up Borisov on its way towards our Sun, unlike ‘Oumuamua which we spotted on its way out of the solar system.

‘Oumuamua’s approach trajectory was behind the Sun, relative to the Earth, when it was on its way in, which meant our telescopes on Earth couldn’t pick it up.

If we’d had a telescope on our orbit on the other side of the Sun, we could have had more warning of ‘Oumuamua’s approach, she said.

Borisov is a proper comet, whereas ‘Oumuamua is what Dr Bannister said is best described as “the husk of a comet” with all its ices baked out.

Borisov is more active than ‘Oumuamua, with its little coma of sublimating ices. Its brightness – it’s reflecting the Sun’s light rather than emitting any visible light of its own – means we can detect it at greater distances from our star.

At two or three kilometres across, it’s bigger than ‘Oumuamua, which is more the size of a single skyscraper at 200 to 300 metres across, which also helps us see Borisov.

“You actually see comet-type stellar objects for larger distances in the solar system, than you can see little rock-type stellar objects,” Dr Bannister said.

The upshot of all this is that it gives astronomers more time to observe Borisov.

Borisov is the first interstellar comet we’ve detected, maybe

‘Oumuamua was weird, Professor Horner said.

At first astronomers thought it was a comet.

Then they decided it was an asteroid.

And then some people went back to the comet theory.

And then, there was that whole other school of thought that it was an alien probe, possibly sent here on purpose.

Borisov has not caused any of the same controversy.

“It’s the kind of thing where if it was coming in more slowly it would look just like a garden-variety comet,” Professor Horner said.

Borisov isn’t that different from comets from our solar system

Don’t let the fact that Borisov looks very similar to comets formed in our solar system disappoint you.

He said Borisov’s similarity to our comets speaks to how universal the formation of cometary bodies is.

While we’ve seen a wide diversity of exoplanetary systems across the galaxy, Dr Bannister said, thanks to the efforts of instruments like the Kepler Space Telescope and the TESS (Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite), that doesn’t mean our solar system is unique.

“What this is telling us is the chemistry that takes place in at least one of those systems, purely by random chance from the heavens, is the same as ours,” she said.

“So maybe we’re not different after all. Maybe we are in fact a remarkably common kind of solar system.”

And that even plays into some of the crazy, science fiction-like ideas that people have come up with over the decades, about life being transferred from planetary system to planetary system by comets, Professor Horner said.

Scientists have detected signs of water on Borisov

Scientists have detected signs of water on Borisov, which we would expect, given that comets are predominantly mixtures of frozen water and other ices.

“So to get water on this thing is just confirmation that comets are comets are comets, wherever they are in the cosmos,” Professor Horner said.

“But it’s also cool to have water that originates around another star — alien water.”

Astronomers have also picked up evidence of cyanogens on Borisov, which again isn’t that surprising, Dr Bannister said.

“Comets are full of cyanide, it’s one of those things,” she said.

The more time we get to train our telescopes on Borisov, means we can study in more detail the gas that’s coming off it, Professor Horner said.

“If we can get good enough measurements of the gas around the comet, then we’ll actually start to be able to dig into the nitty-gritty of the elemental abundances … and also isotopic abundances,” he said.

“Those might actually tell us a little bit more about the conditions this thing formed in, and maybe they’ll reveal subtle differences between our comets and this comet.”

Borisov is coming closer — but it won’t get as close as ‘Oumuamua

Borisov will reach its closest approach to the Sun, or the perihelion of its orbit, on December 7, according to the International Astronomical Union.

At that time it will be about two astronomical units from both the Sun and us, or twice the average distance between the Earth and Sun.

“So it’s outside the orbit of Mars,” Dr Bannister said.

“Whereas ‘Oumuamua was what we’d actually call a near-Earth asteroid, it came within 0.25 astronomical units of us.”

Will we be able to see Borisov?

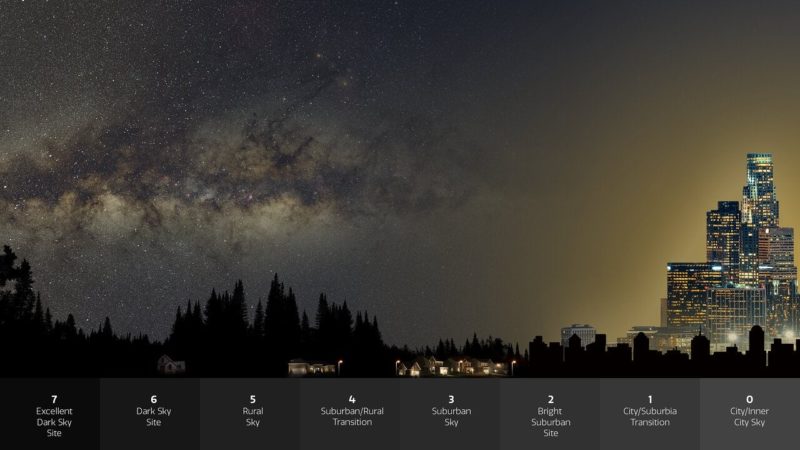

Borisov is expected to get to a peak magnitude of 16 or 15, which will be a factor of 10,000 times too faint to see with the naked eye, Professor Horner said.

“You’d need probably at least a 10- or 12-inch [25 or 30cm] telescope [to see it], probably bigger than that in all honesty,” he said.

If you don’t have the equipment to look at it yourself, Professor Horner recommended getting along to your local astronomy group who might have the sort of telescopic equipment to be able to pick it up.

The best times to see Borisov will be during December and January, where it is expected to be at its brightest in the southern sky, before it begins its journey out of our solar system.

If you do get the opportunity to see Borisov, don’t expect anything too amazing to look at, Dr Bannister said.

“This is a small, faint, fuzzy thing,” she said, although it’s been on a very impressive journey.

And could there by one more twist in Borisov’s tale?

“We sometimes see comets of this sort coming in from the Oort Cloud [in our solar system] just shred themselves into a cloud of fragments at this point when they get heated,” Dr Bannister said.

“Because this may have never been heated by a star before. It could have been travelling for billions of years, we have no way of knowing yet.”

If you miss bidding Borisov a fond farewell, don’t worry. Scientists are already calculating how to pay it a visit.