Are Saturn’s rings young or old? – EarthSky

View larger. | Saturn, via the Cassini spacecraft. Image via NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute/Europlanet.

Four decades ago, when I was first learning astronomy, we all assumed that Saturn’s iconic rings had always been there, as old as the solar system itself. We assumed that Saturn formed with its rings, which are vast and glorious, stretching nearly 200,000 miles (300,000 km) above the planet’s equator. The rings seemed so integral to Saturn itself. But then came the visits to Saturn by Voyagers 1 and 2, in 1980 and ’81. Their observations suggested that the rings might be younger than the planet – much younger – a temporary phenomenon, lasting only millions of years in the 4.5-billion-year lifetime of our solar system. And in recent years, data from the Cassini spacecraft (2004-2017) seemed to nail down the idea that Saturn’s rings are from 10 million to 100 million years old. Now we hear that insight from Cassini wasn’t the final word, either. A team of researchers has reignited the debate about the age of Saturn’s rings with a study that dates the rings as most likely to have formed in the early solar system.

The authors suggest that processes that preferentially eject dusty and organic material out of Saturn’s rings – a “ring rain” that falls in part onto Saturn’s cloudtops – could make the rings appear younger than they really are. Cassini, in fact, encountered this ring rain when it dived between Saturn’s rings and its upper atmosphere during its Grand Finale in 2017.

The idea is being discussed this week by astronomers at a joint meeting of the European Planetary Science Congress and the AAS Division for Planetary Sciences in Geneva, Switzerland. It was published just in time for this meeting, on September 16, 2019, in the peer-reviewed journal Nature Astronomy.

Voyager 2 captured the images to make this composite, taken through ultraviolet, violet and green filters. The image was considered mind-blowingly detailed at the time. The Voyager 1 and 2 Saturn encounters occurred nine months apart, in November 1980 and August 1981. Those missions were what first sparked speculation that Saturn’s rings might be younger than astronomers had always assumed. Image via NASA/JPL-Caltech.

A statement from the new study’s authors said:

Cassini’s dive through the rings during the mission’s Grand Finale in 2017 provided data that was interpreted as evidence that Saturn’s rings formed just a few tens of millions of years ago, around the time that dinosaurs walked the Earth. Gravity measurements taken during the dive gave a more accurate estimate of the mass of the rings, which are made up of more than 95% water ice and less than 5% rocks, organic materials and metals. The mass estimate was then used to work out how long the pristine ice of the rings would need to be exposed to dust and micrometeorites to reach the level of other ‘pollutants’ that we see today. For many, this resolved the mystery of the age of the rings.

But not all scientists were convinced. In an article about Saturn’s rings in Scientific American in August, ring expert Luke Dones of the Southwest Research Institute was quoted as saying:

I have no objection to young rings. I just think no one has found a very plausible way of making them. It requires an unlikely event.

In other words, in the early solar system, when there was a lot of debris flying around, it’s easy to imagine the dynamic processes capable of creating the rings: the capture of debris by Saturn’s gravity and/or the breakup of comets, asteroids, or even small moons. Once the rings began to form, it’s also easy to imagine the separate ring particles colliding with each other and breaking up even smaller, spreading out around Saturn to form its rings. But, the Scientific American article said:

… it is just too hard, some critics say, to craft such expansive rings in the relatively placid solar system of now and near-yesteryear.

Astronomer Aurélien Crida, via OCA. He is lead author of the new study suggesting Saturn’s rings are very old.

Aurélien Crida of the Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur, is lead author of the new study. Here’s why he believes the debate is not yet settled; he said:

We can’t directly measure the age of Saturn’s rings like the rings on a tree-stump, so we have to deduce their age from other properties like mass and chemical composition. Recent studies have made assumptions that the dust flow is constant, the mass of the rings is constant, and that the rings retain all the pollution material that they receive.

However, there is still a lot of uncertainty about all these points and, when taken with other results from the Cassini mission, we believe that there is a strong case that the rings are much, much older.

Crida and his colleagues argue in their study that the mass measured during the Cassini mission finale is in “extraordinarily good agreement” with models of the dynamical evolution of massive rings dating back to the primordial solar system.

Galileo discovered Saturn’s rings in 1610. Through his early telescope, he thought they looked like “handles,” or perhaps large moons on either side of Saturn. Christiaan Huygens then took up the observations of Saturn and published this compilation image, showing how Saturn’s appearance had changed from 1610 to 1646, in his Systema Saturnium. It was Huygens who revealed the mystery of Saturn’s rings, saying were “It [Saturn] is surrounded by a thin, flat, ring, nowhere touching, inclined to the ecliptic.” Read more history of our knowledge of Saturn’s rings.

Nadia Drake, author of Scientific American’s Saturn article in August, described Saturn’s rings as “icy particles ranging in size from microscopic to mobile home.” Crida and colleagues described the individual components in Saturn’s rings more prosaically as:

… particles and blocks ranging in size from meters down to micrometers. Viscous interactions between the blocks cause the rings to spread out and carry material away like a conveyor-belt. This leads to mass loss from the innermost edge, where particles fall into the planet, and from the outer edge, where material crosses the outer boundary into a region where moonlets and satellites start to form.

More massive rings spread more rapidly and lose mass faster. The models show that whatever the initial mass of the rings, there is a tendency for the rings to converge on a mass measured by Cassini after around 4 billion years, matching the timescale of the formation of the solar system.

Crida summed up his team’s position, saying:

From our present understanding of the viscosity of the rings, the mass measured during the Cassini Grand Finale would be the natural product of several billion years of evolution, which is appealing. Admittedly, nothing forbids the rings from having been formed very recently with this precise mass and having barely evolved since. However, that would be quite a coincidence.

Hsiang-Wen (Sean) Hsu of LASP and his colleagues reported in 2018 that they successfully collected microscopic material streaming from Saturn’s rings. Read more.

Hsiang-Wen Hsu of the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics (LASP) in Boulder, Colorado, was part of a team that announced results in October 2018 related to a “ring rain.” The results, via Cassini, showed that 600 kilograms (1,300 pounds) of silicate grains fall on Saturn from the rings every second. Other studies have shown the presence of organic molecules in Saturn’s upper atmosphere that are thought to derive from the rings. Hsu commented:

These results suggest that the rings are ‘cleaning’ themselves of pollutants. The nature of this potential ring-cleaning process is still mysterious.

However, our study shows that the exposure age is not necessarily linked to the formation age, thus the rings may appear artificially young.

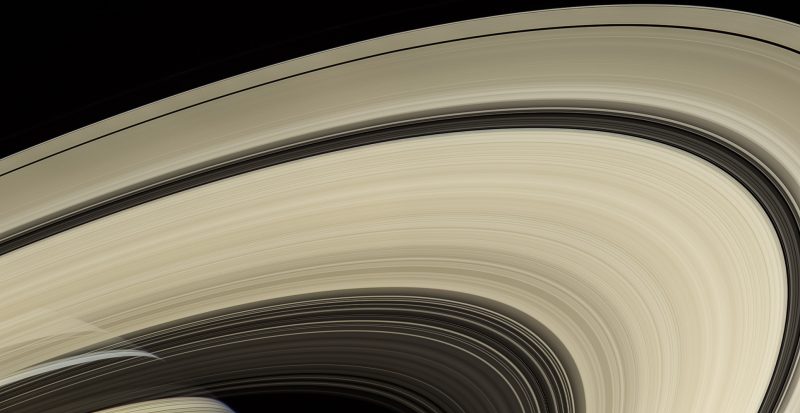

View larger. | Another Cassini image of Saturn’s rings, via NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute/Europlanet.

Bottom line: Cassini data seemed to indicate rings lasting only 10 million to 100 million years. A new study suggests that dusty and organic material ejected from Saturn’s rings – a “ring rain” – could make the rings appear younger than they really are. As things stand now, we don’t know if Saturn’s rings are young or old; we only know that astronomers are continuing to learn about them.