An investor’s guide to space, Wall Street’s next trillion-dollar industry – CNBC

(This story is part of the Weekend Brief edition of the Evening Brief newsletter. To sign up for CNBC’s Evening Brief, click here.)

The space industry is in the middle of a widespread transformation, as the last decade has seen a number of young companies begin to seek to profit in an area where most of the money was made from military contracts or expensive communications satellites.

The estimated $400 billion space economy is still largely dominated by large aerospace and defense companies, serving government-funded interests. But investors say that’s changing, with Morgan Stanley, Goldman Sachs, Bank of America and UBS each issuing frequent research for clients on how the space industry is growing. Wall Street’s consensus is that space will become a multitrillion-dollar economy in the next 10 to 20 years — a view investors today are banking on.

“It’s absolutely a viable industry to invest in, just like software,” Bessemer Venture Partners’ Tess Hatch told CNBC. Hatch has led Bessemer’s investment in several space companies, sitting on the board of Rocket Lab and satellite company Spire Global, among others.

As both aerospace giants and private capital continue to invest billions of dollars in new technologies and opportunities, public investors should know the biggest players in the space business.

This is your guide to investing in space right now, with insight on the top space companies from analysts and investors.

SpaceX launches the first Block 5 version of its Falcon 9 rocket for the Bangabandhu Satellite-1 mission.

SpaceX

Shannon Saccocia, chief investment officer at Boston Private, told CNBC she recognizes the space industry is largely government-driven at the moment and is looking for more companies to come to market.

“I think that space is more than just a government-funded pursuit; it needs to be more of a privatized venture. My hope is that this will fund some additional social impact,” Saccocia said. “There is a desire for this to be treated more as an opportunity for companies to benefit the social good, rather than something that needs to be protected from a national security perspective, which I still think that space falls into that paradigm.”

There are a number of ways to categorize space companies, as the industry bleeds over into a variety of other sectors. For the purpose of this guide, CNBC simplifies investor opportunities into four categories: Human spaceflight, national security, satellite communications, and imagery and data analysis.

Additionally, each of those categories includes three different types of companies: Public companies that are purely space-focused, public companies with exposure through a significant space subsidiary and private companies that soon may either go public or spin off divisions.

Here’s what you need to know.

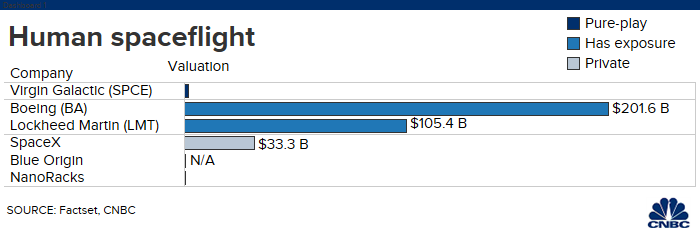

Investing in human spaceflight

While Boeing and Lockheed Martin both have legacies in human spaceflight, Virgin Galactic is the first publicly traded company focused on flying people to space as its primary business. Virgin Galactic debuted with much fanfare at the New York Stock Exchange last month, with institutional investors taking notice.

Renaissance Capital’s Matt Kennedy, a specialist in IPO strategy, told CNBC much of the initial excitement around Richard Branson’s venture was “because it was the first publicly traded space tourism company.”

Virgin Galactic’s spacecraft Unity heads to space for the first time.

Virgin Galactic | gif by @thesheetztweetz | CNBC

“This is extremely significant for the space community, as — other than Skybox being acquired by Google and MDA acquiring Digital Globe — this is really the third liquidity event in the space industry and it’s another invitation for investors to invest in the space sector,” Hatch said. “This is just the first step for many, many other larger and more significant space opportunities.”

Virgin Galactic shares similarities with two other space ventures built by billionaires this century: Blue Origin and SpaceX. The former is also developing a rocket for space tourists, while the latter plans to use its massive Starship rocket as a means of traveling from one place to another on Earth quickly, known as point-to-point space travel. Virgin Galactic recently announced an investment from Boeing, as the venture is looking at whether it can mature its space tourism technology and build rockets capable of point-to-point high-speed travel.

“The thing to note about space is that the feedback cycle is a bit longer,” Hatch said. “While that might take a bit longer, I do think it will have the same return on your investment as a software company.”

Neither SpaceX nor Blue Origin plan to go public any time soon. But it would be a mistake to miss the impact the companies of Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos have had on the industry. SpaceX has become the most active U.S. rocket launcher, significantly reducing the cost of launching satellites while also proving it can reuse the most valuable parts of rockets by landing the boosters. SpaceX has also been working on a capsule known as Crew Dragon, aiming to begin launching astronauts to the International Space Station for NASA next year.

Although Blue Origin has yet to fly people, the company has taken what it’s learned from its space tourism program and applied it to a variety of ambitious spaceflight endeavors: Developing a powerful yet reusable rocket engine, building a massive new rocket and leading a bid to fly cargo and people to the moon for NASA on a lunar lander.

Lockheed Martin joined Blue Origin’s lunar lander initiative and has also been building the Orion capsules for NASA’s deep space missions. NASA has already committed to buying six Orion spacecraft from Lockheed Martin for a minimum of $4.6 billion — and the agency may plunk down even more money in the future.

Boeing, like SpaceX, is developing a capsule to fly NASA astronauts to the space station. Boeing will get as much as $4.2 billion from NASA to build the spacecraft, called Starliner, to end the United States’ dependence on flying with Russia to get people to orbit. Additionally, Boeing is the prime contractor for NASA’s Space Launch System, or SLS, an immense rocket intended to send astronauts to the moon and more. But SLS is several years behind and billions of dollars over budget in development, with a recent White House budget document noting that it will cost more than $2 billion per launch.

Lastly is NanoRacks, a private company that focuses on a variety of human spaceflight opportunities ranging from research to space station habitats. NanoRacks has a wide swath of customers as well, ranging from NASA to the European Space Agency to a number of private U.S. companies.

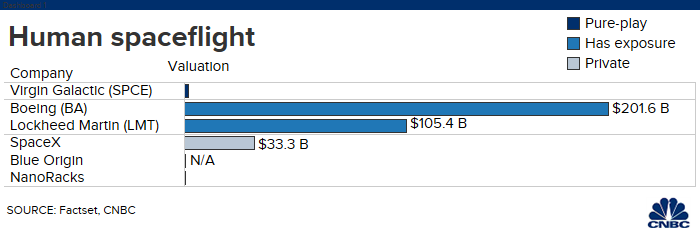

Investing in national security space

While human spaceflight may be the most esteemed part of the industry, building and launching spacecraft for the U.S. military has long been a consistent line of business for many defense companies. Because of that, other than Aerojet Rocketdyne, the space divisions are only a small part of most public companies in the national security category.

“A lot of them are getting maybe between 5% and 20% or so of their revenues from space-related activities,” said Andrew Chanin, co-founder and CEO of Procure AM, a firm that earlier this year issued a space-focused exchange traded fund, or ETF, called UFO.

Aerojet Rocketdyne focuses on propulsion systems for a variety of military and commercial rockets and spacecraft. The company’s stock has had a solid year, up more than 25% on the back of continued sales growth of its rocket engines. In 2018, billionaire investor Mario Gabelli identified Aerojet Rocketdyne as one of his top stock picks, noting CEO Eileen Drake “has done a fantastic job of running this company.” But last year Aerojet Rocketdyne lost out to Blue Origin when bidding its AR1 engine for United Launch Alliance’s new Vulcan rocket. Despite the missed opportunity, Aerojet Rocketdyne’s most recent quarterly report said it expects to see 2019 as another year of sales growth.

Northrop Grumman last year bought Orbital ATK, one of the top suppliers of solid rocket motors, and renamed the company Northrop Grumman Innovation Systems. Beyond building spacecraft to send cargo to the International Space Station, Northrop’s space unit is also developing its OmegA rocket for a competitive batch of U.S. Air Force launch contracts.

United Launch Alliance, or ULA, is a joint venture owned by Boeing and Lockheed Martin. Before the arrival of SpaceX as a challenger, ULA was the sole provider of U.S. Air Force launches for several years.

Space is only a minor part of what most companies in this category do, as Chanin explained the barriers to entry are lower for defense giants.

“One of the big pieces, before the government is signed off on a contract, is the background checks and due diligence on the actual companies, making sure that they have the proper safeguards in place,” Chanin said.

Therefore, on quarterly reports, several companies either don’t break space out as a separate business unit or include it within its aerospace business. Those companies include Honeywell, Raytheon, L3Harris Technologies and Ball Aerospace — all of which book millions of dollars in space revenues each quarter.

“That said, not every company can specialize in every single space business, and that allows for the opportunities for companies like SpaceX and Blue Origin to make appealing cases for why their company should be considered,” Chanin said.

Sierra Nevada Corporation, or SNC, is another private company that should not be overlooked. As is the case of other defense contractors, space is only a part of what SNC does. But the company has steadily built its space business, with its reusable cargo spacecraft Dream Chaser as one of the most visible parts.

“What we’ve seen recently is the government — not just the U.S. but even abroad — is government’s willingness to work with your newer and even smaller, more start-up, the companies on that scale,” Chanin said.

The final batch of national security companies comprises several private rocket builders. At the top of the heap is Rocket Lab, a company building and launching small rockets to specific orbits, with nine successful launches under its belt. Then there’s Virgin Orbit, a spinoff of Branson’s Virgin Galactic, which is about to attempt its first rocket launch and uses a modified Boeing 747 jet as its mobile launchpad. Finally, investors should keep an eye on both Firefly Aerospace and Relativity Space — the former is only a few months away from its first launch, and the latter is taking an ambitious, 3D printing approach to transforming the rocket manufacturing process.

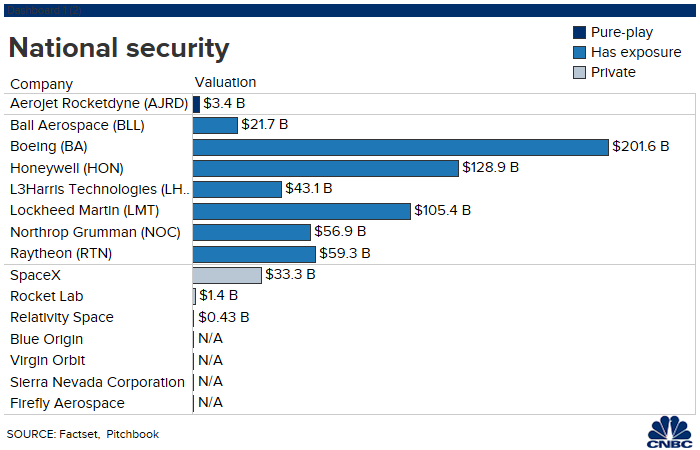

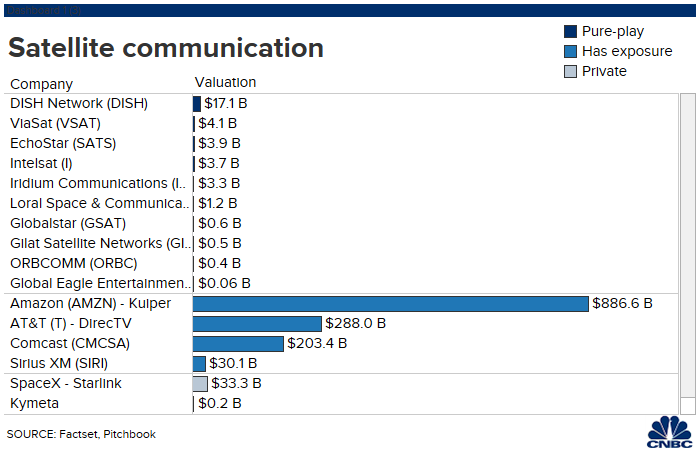

Investing in satellite communications

The business of satellites is varied, as it stretches from manufacturers to broadband video providers to operators and ground systems companies. The majority of satellite-focused businesses therefore fall under the broad category of satellite communications — for the sake of simplicity and because many of the manufacturers feature in the national security category.

But for investors looking to invest in the space industry now, satellite communications offers the highest number of pure-play public companies. The largest of those by market value is DISH Network, which owns and operates a fleet of direct broadcast satellites. DISH used to be a service provided by EchoStar, another company on this list that provides several communications services beyond just broadcast television.

ViaSat, Intelsat and Loral Space & Communications each focuses on broadband services, including internet, via large satellites that orbit in a fixed position but far away from the Earth, to cover as much area as possible. For example, ViaSat-1 is a seven-ton satellite that covers much of North America.

Iridium Communications and Globalstar both offer a variety of satellite phones and other mobile communications services. Iridium is often heralded as one of the space industry’s turnaround stories, as the company recovered from bankruptcy over a decade ago to complete its $3 billion Iridium NEXT network of satellites this past year.

An increasing number of satellite companies are looking to offer Internet of Things, or IoT, communication services, and ORBCOMM markets itself as one of the leading providers in that niche. And, in the often-overlooked but critical business of ground stations, Gilat Satellite Networks, although based in Israel, trades on the Nasdaq and focuses on transportable and relatively small antennas.

Smallest among the pure-plays is Global Eagle Entertainment, a provider of entertainment and internet services for airlines. While the stock once traded above $10, shares have plummeted since 2014 and most Wall Street research firms no longer cover Global Eagle Entertainment’s stock.

“In many cases, satellites are this essential part of the infrastructure,” Chanin said. “They’re operating as the digital data superhighway toll operators. So if you expect there’s going to be a data explosion, satellites might be one of these more overlooked areas that are essential components in this infrastructure.”

The largest telecommunications companies in the world have satellites as a part of broadcast distribution, whether it’s AT&T with DirecTV or Comcast. Sirius XM also operates a small fleet of satellites, to distribute its radio services.

There’s also a new competition in satellite communications: The race to build extensive networks of hundreds or even thousands of small satellites to provide high-speed internet. A group of satellites are often known as “constellations,” but the plans of SpaceX, OneWeb, Telesat and more would launch so many satellites that they’re being called “megaconstellations.”

Amazon‘s recently unveiled internet satellite program Project Kuiper represents one way investors can bet on these megaconstellations. Project Kuiper would put 3,236 satellites into orbit, and the company is already building facilities on the ground through its new AWS Ground Station division.

OneWeb was one of the early companies pursuing an internet constellation, as the company aims to launch 650 satellites into orbit over the next two years. OneWeb has raised $3.4 billion since its inception in 2012, with investments from a wide variety of sources: Japanese conglomerate SoftBank, Mexican conglomerate Grupo Salinas, Qualcomm, the Rwandan government, Virgin Group, Coca-Cola, Airbus, Intelsat, EchoStar-owned Hughes Communications and Indian conglomerate Bharti Enterprises. According to PitchBook, OneWeb was valued at $14 billion in June 2017, during a failed acquisition attempt by Intelsat.

But likely the most ambitious internet constellation effort is SpaceX’s Starlink. Musk’s company has been steadily fundraising this year. Starlink would include as many as 30,000 satellites when completed and President Gwynne Shotwell claimed recently that her company’s network is far ahead of OneWeb, saying “we have far more capacity per satellite than our competitors.” SpaceX launched 60 Starlink satellites in May, expects to launch another 60 Starlink satellites next week and aims to be launching 60 every other week soon.

Disclosure: Comcast is the owner of NBCUniversal, parent company of CNBC and CNBC.com.

Investing in imagery and data analysis

The last category is the smallest by total market value, but, thanks to the past decade of private investment, the imagery and data analysis category may be the fastest to grow in the coming years.

Essentially four space companies in one, Maxar Technologies could easily be included in either national security or satellite communications. But, having acquired DigitalGlobe in 2017, Maxar operates what it claims is “the world’s most advanced constellation” of imaging satellites.

Chad Anderson, CEO of small New York City firm Space Angels, told CNBC that he sees potential from companies making use of the new flood of geospatial imagery, which he described as satellites “providing information about the world around us, spatially, so we understand where things are and where they’re moving.” He compared geospatial imagery today to the development of the Global Position System, or GPS, in the late 1970s.

“There was a lot of infrastructure investment in GPS, meaning that there was government investment into military applications, to put these satellites up and give us this new global positioning,” Anderson said.

Anderson explained that companies such as Trimble and Magellan created the distribution channel for GPS, unlocking the feed of data for the rest of the world. Garmin has focused on the consumer applications of GPS, through a wide variety of devices.

“They made it accessible to the tech community, and this is where you see all of the value being generated. The founders of didn’t have to know how satellites work … you just have to know that signal is there and gives you this information,” Anderson said. “The GPS signals from space are incredibly valuable. The geospatial intelligence signals that we’re just starting to harness today are extremely valuable.”

Finally, there are several private companies focusing on different areas of imagery and data analytics. Bessemer’s Hatch called out Spire Global, Planet Labs and Orbital Insight as three “high-flying venture-backed companies” that may go public soon. Spire Global and Planet Labs each operate constellations of small satellites, with the former collecting data on things such as the weather and the latter taking regular images of the Earth’s surface. Although both companies have since raised money, Planet was valued at $2.2 billion in August 2017 and Spire Global was valued at $345 million in November 2017, according to PitchBook.

“I’d keep an eye on those,” Hatch said.

Patience is necessary

Each of the investors CNBC spoke to pointed out how historically unique it is to see companies looking to profit from space. But even with the declining costs in space hardware, any business in space faces steep capital costs and high risks. As Ann Kim, managing director of Silicon Valley Bank, pointed out, Virgin Galactic shares could easily continue to be volatile until its business operations stabilize.

“The public is buying shares in a company with ambitious plans to make space a viable destination, rather than one with a predictable business model. Investors should expect the shares to be extremely volatile due to a number of uncertainties in this market,” Kim said.

But that’s not to say Virgin Galactic is representative of all space companies. Renaissance’s Kennedy sees how the past decade of private investment in space should gain traction on the public markets.

“If a venture-backed company with strong growth files for an IPO, I think they’ll get investor interest — they just have to prove that their model works,” Kennedy said.

In the past decade $24.6 billion in private capital has gone to space companies, with a total of 509 companies receiving investment. Additionally, 2019 is on pace for a new annual space investment record, as the first nine months of this year saw $5 billion of private investment across 146 rounds. That’s according to the most recent quarterly report from Space Angels, which also invests exclusively in space companies.

“Space is the vantage point that allows us to do business,” Anderson said. “It’s what links our financial markets, shipping lanes — the global economy as it exists today would not exist without space.”

Saccocia added that her clients have only begun to think about space investments “as a secondary derivative” of climate change ventures, so it’s still a new concept to many public investors.

“I think some of my very climate change-centric clients have broached this, saying things like ‘we need to learn more about planets other than ours and maybe hopefully help ours in turn,’ but I haven’t had a lot of requests for space in particular as a specific investment theme,” Saccocia said.