A Mercury Transit for the Ages: November 1973 – Space.com

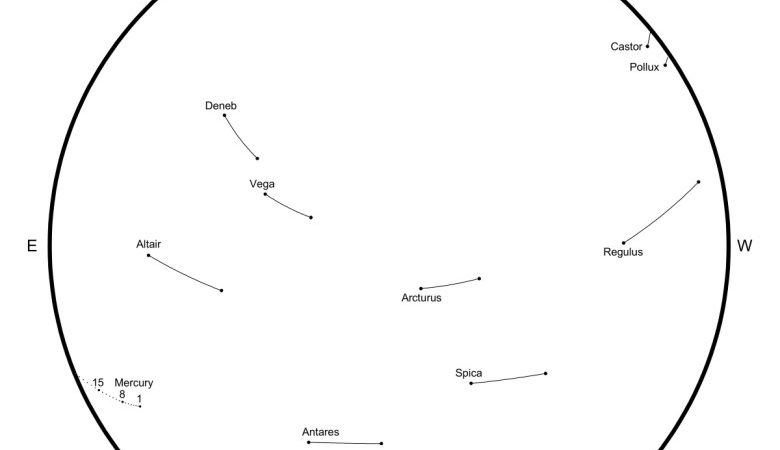

On Monday (Nov. 11), Mercury will pass between the sun and Earth and will appear as a tiny silhouette moving across the disk of the sun. This event, called a transit, is a relatively rare occurrence and will be the last of its kind to be visible from North America until 2049.

In my long career as an assiduous amateur astronomer, I’ve seen other transits of Mercury, but one from November 1973 stands out, for two reasons: the viewing location, and the intrigue of trying to accurately time when Mercury would ultimately slide off the disk of the sun.

Related: Mercury Transit 2019: Where and How to See It on Nov. 11

This story actually began in 1967, when the founder and president of a local astronomy club, Ron Abileah, approached the management of New York’s Empire State Building with an unusual request. At the time, the local astronomy club, the Amateur Observers’ Society of New York (AOS), was composed primarily of budding amateur astronomers, who were also in their teens. Abileah’s request was for the AOS to observe a total lunar eclipse from the famous skyscraper’s 86th-floor observation deck. The problem was that the eclipse was to occur during the predawn hours, when the Empire State Building was normally closed to the general public. The building’s management told Abileah that they would allow the AOS to watch the eclipse from the observation deck — but only if the AOS paid to have a security guard on duty.

The full moon is seen next to the Empire State Building during a total lunar eclipse on Sept. 27, 2015.

(Image credit: Joel Kowsky/NASA)

The club agreed to these terms, and in the early morning of Oct. 18, 1967, 10 boys and two girls, ages 13 to 17, trooped up to the Empire State Building’s observation deck, carrying two 6-inch telescopes, binoculars, tripods, monoculars (handheld telescopes), a radio for shortwave time signals and a guitar. Meanwhile, New York’s Hayden Planetarium had planned to hold an eclipse watch at the Sheep Meadow in Central Park, with astronomers explaining the various stages of the eclipse to the general public. But those plans were scrapped when fog and low clouds rolled in just before the eclipse began. The planetarium also had planned to photograph the eclipse from the top of the United Nations Secretariat Tower, but that plan was also clouded out; in Washington, D.C., the United States Naval Observatory also drew a blank.

But the AOS successfully viewed the eclipse, albeit in conditions that had some of the adventure and most of the discomfort of a fogbound ship at sea. Because the 86th-floor observation deck rises to over 1,000 feet (300 meters) above the city streets, there were periods when the eclipsed moon broke through the low cloud deck. As one of the young astronomers later commented, “The fog kept rising and lifting and dipping.” The publicity that followed was extremely favorable for the teens. The New York Times headline on Oct. 19, 1967 (page 49) trumpeted:

“The Young See Moon in Eclipse as Their Elders Fail to Show Up.”

Daniel J. Howe, from the Empire State Building’s management, was so happy with the outcome that he refunded the AOS the cost for having the security guard and invited the club to come back anytime there was another major astronomical event.

Fast-forward to Nov. 10, 1973.

On that second Saturday of November in 1973, Mercury was to cross in front of the sun. But from New York, much of the event would occur below the eastern horizon. Mercury would begin encroaching onto the sun’s disk at 2:47 a.m., well before sunup. Sunrise would not come until 6:35 a.m., and Mercury would move off the sun’s disk at 8:17 a.m., with the sun still quite low in the sky.

But from the Empire State Building’s observation deck, getting a clear shot at the sun would not be a problem. So, the AOS requested that they conduct observations of the transit from there, and that request was granted.

There would be one problem, however, in trying to record the various phases of the transit from that very famous edifice. Rising over 200 feet (60 m) above its 102nd floor is a tower that transmits both television and FM radio signals. But as AOS members quickly found out, when shortwave radios were used to receive accurate time signals, the interference produced by the broadcasts emanating from the transmission tower drowned out the shortwave signals.

For the 1973 transit of Mercury, a few AOS members wanted to try making accurate observations of when the disk of Mercury appeared to move off the sun. But how could this be done when shortwave frequencies were not clearly audible?

That’s when one AOS member came up with a novel solution: Why not get one of the local NY FM radio stations to retransmit the shortwave time signals over their airwaves? Because that station’s FM signal would emanate from the transmission tower at the Empire State Building, there would be no problem in hearing the shortwave transmission.

The time signals would be from radio station WWV out of Fort Collins, Colorado. The FM station that was selected to broadcast the WWV signal was WBAI-FM, a noncommercial, listener-supported radio station licensed to New York City.

As it turned out, the AOS member who made the suggestion also happened to work at WBAI. After getting permission from the Federal Communications Commission to retransmit the WWV time signals, a 5-minute block was set up between 8:15 and 8:20 a.m. EST for WWV to be freely heard throughout the New York Tri-State area over WBAI’s FM frequency of 99.5 MHz.

In the years since this episode took place, I’ve often wondered about those who might have been casually flipping through the FM dial and what they must have thought when they accidentally stumbled across the distinctive time ticks and tones of WWV that morning! Of course, prior to and just after the “5minute time serenade” came an explanation about the transit of Mercury and the importance of securing an accurate timing of Mercury exiting off the sun’s disk.

There is an amusing postscript to this story. When all of the arrangements were made, there was only one thing left to do: bring an FM radio receiver to the Empire State Building on the morning of the transit. One AOS member, named Steve, said he would bring his brother’s multiband “boom box” radio to receive WBAI. On the morning of the transit — which was clear, windy and cold — about a dozen AOS members were set up on the 86th-floor observation deck. But Steve didn’t arrive until minutes before the end of the transit.

Glenn Schneider, who was the president of AOS at the time and who many years later would attain his goal of earning a doctorate in astronomy, breathlessly ran up to Steve, asking, “Do you have the radio? That’s essential, and we’re running out of time!” Steve sheepishly replied, “No, my brother wouldn’t let me borrow it; that’s why I’m so late.”

Glenn screamed so loud that I’d bet it could have been heard from Brooklyn. “For God’s sake!” he exclaimed. “Does anybody up here have an FM radio?”

That’s when I said, “Yes, I do,” and out of my pocket, I pulled out a small transistor radio no bigger than a deck of cards. Glenn quickly pulled off the back of the radio and, using alligator clips, attached it to a reel-to-reel tape deck, which began recording WBAI just as our associate at the station switched over to the WWV signal. And ultimately, we were successful in accurately recording those precious moments when the leading edge of the black disk of Mercury first touched the edge of the sun and a couple of minutes later, when its trailing edge moved off the sun.

It’s been 46 years since that event. And just a few days ago, I received an email from Glenn regarding next Monday’s transit. He finished by asking, “P.S. Are you bringing a boom-box radio for this one?”

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York’s Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers’ Almanac and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for Verizon FiOS1 News in New York’s lower Hudson Valley. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Need more space? Subscribe to our sister title “All About Space” Magazine for the latest amazing news from the final frontier!

(Image credit: All About Space)