Is Betelgeuse about to blow?

Probably not, but astronomers are having fun thinking about it.

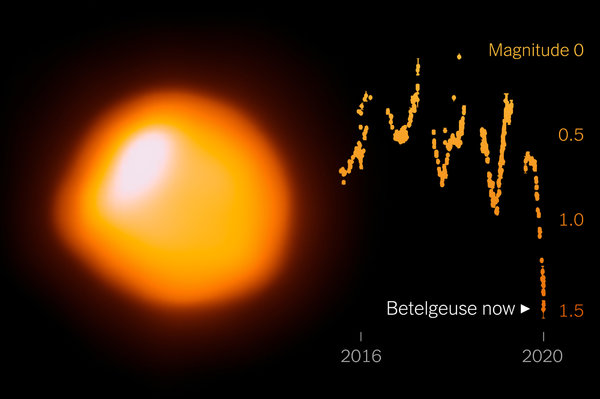

Over the last three months, the star, which marks the armpit of Orion the hunter, has mysteriously dimmed to less than half its normal brightness, markedly altering one of the great sights of the winter sky.

At the beginning of January the star was fainter than ever before observed, according to Edward Guinan of Villanova University, who has been compiling data on Betelgeuse. In its “fainting” spell, Dr. Guinan said, the star has dropped from seventh to twenty-first on the list of brightest stars in the sky. But even so dimmed, Betelgeuse is still too bright to be easily observed and measured by large professional telescopes — at least not without damaging sensors that were designed to wring every faint photon from the blackness of space.

Rebecca Oppenheimer, an astrophysicist at the American Museum of Natural History in New York, said she had managed to observe Betelgeuse with the 200-inch telescope at Palomar Observatory in California last week, but it had left an afterimage that put their detector out of service for a day. The next time around, she said in an email, they plan to cover part of the giant mirror, to cut down on the amount of light it receives.

“Ha ha, kind of ridiculous,” she wrote. “But, well, the science must go on!”

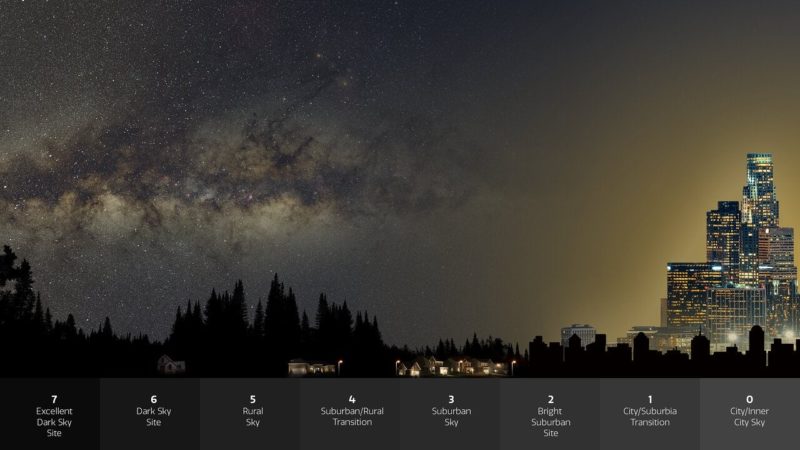

Last week Neil deGrasse Tyson, director of the Hayden Planetarium in New York, circulated a request for amateur astronomers to observe and monitor Betelgeuse’s brightness.

All this has raised the issue of Betelgeuse’s mortality, and its cosmic endgame.

It could be a long wait.

That the star will eventually blow up, nobody denies. Betelgeuse — sometimes pronounced “beetle-juice,” and also known as Alpha Orionis — is at least 10 times and maybe 20 times as massive as the sun. If it were placed in our solar system, its fiery gases would engulf everything out to Jupiter’s orbit.

The star is a so-called red supergiant in the last violent stages of its evolution. It has already spent millions of years burning primordial hydrogen and transforming it into the next lightest element, helium. That helium is burning into more massive elements. Once the core of the star becomes solid iron, sometime within the next 100,000 years, the star will collapse and then rebound in a supernova explosion, probably leaving behind a black hole.

That will be quite a show. Betelgeuse is only 700 light years from Earth, far enough to not kill us when it goes, but close enough to impress; the supernova would be as bright as a full moon in our sky.

The star’s current diminution probably does not mark The End, astronomers say. Aging stars are notoriously cranky and moody, coughing out bursts of gas and dust that obscure themselves, or sputtering inside as their cores evolve and change.

Even normal stars are subject to periodic fluctuations in brightness. Betelgeuse endures such cycles of ups and downs, and the most likely explanation for the current episode is that two cycles bottomed out at the same time.

“My money all along has been that Betelgeuse is going through a somewhat extreme, but otherwise normal quasi-periodic change in brightness,” said J. Craig Wheeler, a supernova expert at the University of Texas in Austin.

Dr. Tyson agreed that coinciding cycles was the most sensible explanation for Betelgeuse’s dramatic drop, although if that’s the case, he said, it was surprising that nobody predicted it.

“You would not expect the coincident minima of two cycles, long and short, to manifest within just a few months, without some hint it was headed there in a previous minimum,” he wrote in an email.

Another “more pedestrian, but still very interesting possibility,” Dr. Wheeler said, is that the star had simply ejected a cloud of dust that was now temporarily blocking some of the starlight. Other studies suggest that shock waves from a stellar core on the verge of collapsing could also cause the star to brighten and then dim about a year from the ultimate explosion.

So, nobody really knows. Astronomers have little data on how stars behave before they explode; supernovas are rare, and they typically happen to distant stars that had not been noticed or studied before.

There are some clues, however, according to Robert Kirshner, an astronomer who is the chief program officer for science of the Moore Foundation. Data from a star that went supernova in 1987 in the nearby Large Magellanic Cloud, a satellite of the Milky Way, and from stars in more distant galaxies, show evidence that those stars were losing mass in the years, decades and centuries before they exploded, Dr. Kirshner said.

But don’t hold your breath waiting for the Big Boom, said Alexei Filippenko, an astronomer at the University of California, Berkeley — “unless you’re good at holding your breath for 100,000 years.”

Then again, Dr. Wheeler said, “we all know that nature can sometimes throw mean curveballs.”

The whole world is watching Betelgeuse now. Even if it doesn’t explode next year, astronomers are bound to learn how a red supergiant behaves and evolves as it approaches its death rattle.

“I go out even on partly cloudy nights just to take peek on what the star is doing,” Dr. Guinan, emailing from an astronomical convention in Honolulu, said. “It would be neat if it suddenly brightened.”