The Existential Wonder of Space – The Atlantic

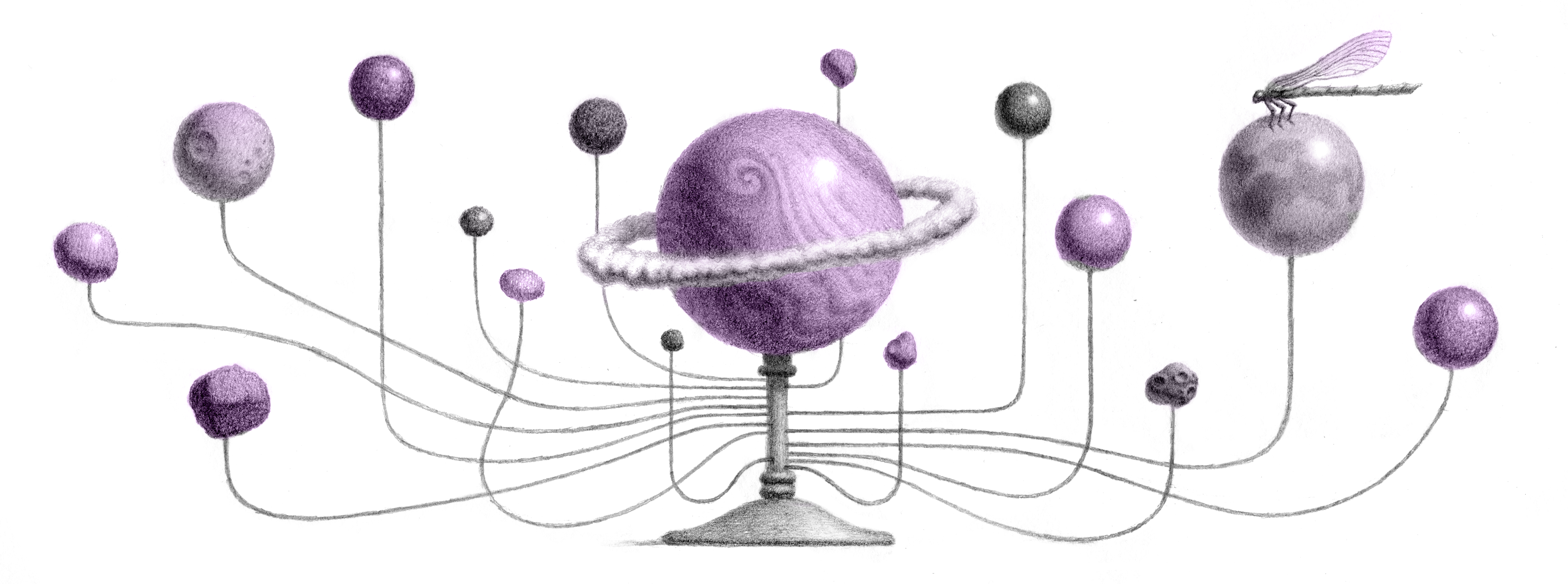

Of all the moons in the solar system, Saturn’s largest satellite might be the most extraordinary. Titan is enveloped in a thick, hazy atmosphere, and liquid methane rains gently from its sky, tugged downward by a fraction of the gravity we feel on Earth. The methane forms rivers, lakes, and small seas on Titan’s surface. Beneath the frigid ground, composed of ice as hard as rock, is even more liquid, a whole ocean of plain old H2O.

The wildest part about Titan—the best part, perhaps—is that something could be living there. NASA is currently working on a mission, called Dragonfly, that would travel to the faraway moon and search for potential signs of alien life, past and present. A helicopter will fly around and study the local chemistry, checking whether conditions may be right for microbes to arise. Hypothetical Titanian life-forms could resemble the earthly varieties we’re familiar with or be something else entirely, feeding on methane compounds the way we rely on oxygen.

The planetary-science community is extremely eager to get a robot over there and start exploring. No spacecraft has visited Titan since 2005—the farthest landing a robot had ever made from Earth—and that mission was short-lived: The lander sampled the atmosphere on its descent to the surface and ran out of power three hours after touching down. That was a glimpse of Titan; scientists want to bask in the landscape, and soon. Technicians are already testing some of Dragonfly’s hardware. The mission, if it launches on schedule, will reach Titan in … 2034.

2034! That’s the space biz for you. The solar system (not to mention the galaxy and the rest of the universe) is big, and getting around it can take years. When NASA announced the Dragonfly mission a few years ago, I imagined my future self, still employed as a space reporter, covering the triumphant landing. If the universe allows it, I realized, I’ll be 44 when the spacecraft lands on Titan. When I did that math, I experienced a twinge of something between surprise and discomfort.

Welcome to the Space Calculator

Ready to get existential? Enter your birth year.

Ready to get existential? Enter your birth year.

Ready to get existential? Enter your birth year.

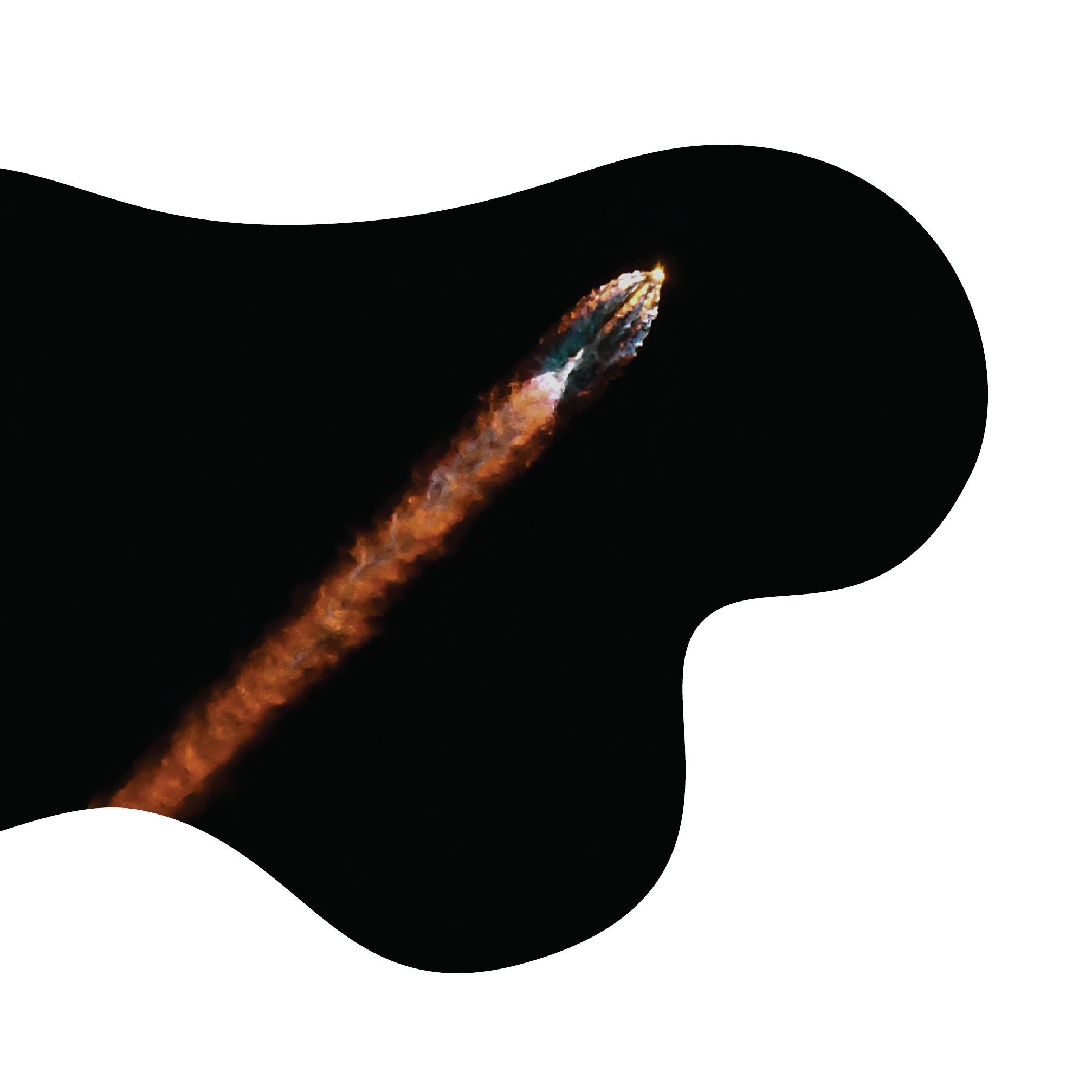

The more I think about the space events of the future, the more existentially unmoored I feel—especially when those moments are far away. Consider Halley’s Comet, a celestial object that periodically whizzes past Earth on its loop around the sun. I was not yet born the last time the comet appeared in the night sky, delighting spectators in 1986. I know for a fact that the next sighting will come in 2061. But I don’t know if I’ll live to 71 to see it.

Contemplating that feels almost like motion sickness, as if I’m riding an emotional version of Space Mountain, with celestial events playing out overhead. I’ve come to think of this feeling as cosmic introspection. It can be unnerving and melancholy but also thought-provoking. “You’ve imagined that end point, but all the details in those intervening years are fuzzy,” Alice Gorman, an archaeologist at Flinders University who focuses on space exploration, told me. “You can feel any way you want to about them.” So, let’s take a little trip into the future. How old will you be when a little helicopter soars through methane skies in an alien world, or when a familiar comet makes its return? And how, exactly, does that make you feel?

You Were Born in

We ran the numbers, and you will be

49years old when the Dragonfly mission reaches Titan

We ran the numbers, and you will be

49 years old

when the Dragonfly mission reaches Titan

We ran the numbers, and you will be

49 years old

when the Dragonfly mission reaches Titan

To understand why the future of space makes me feel some kind of way, I reached out to a few astronomers, who tend to perceive the passage of time differently than the rest of us do. These are people who think in light-years and obsess over starlight that took billions of years to reach Earth. What feels to me like a temporal abyss—11 years—is a wisp of time to Heidi Hammel, an astronomer at the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy. Hammel told me that at a recent meeting about future space-based telescopes, she and her colleagues remarked, without a hint of irony, that the first observatory of this particular set could potentially launch in “only 12 years,” and that the entire suite could be in operation in “only 22.”

She knows, of course, how much can change, on a human scale, in two decades. Hammel spent that long working on the James Webb Space Telescope before it finally launched in 2021 and started observing the universe in unprecedented detail. In her science talks, she includes a picture of herself at the beginning of the project, with her youngest son in a baby carrier. Now her son is a graduate student who towers over her.

Before the Webb telescope, Hammel worked on the Voyager missions, NASA’s grand tour of the outer planets in the solar system. She was in the room at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory when Voyager 2 flew past Neptune in 1989. But back when the effort began, Hammel was in elementary school. Now thinking about those kids who will someday measure their life against space milestones is “an emotional thing,” she said. “I don’t know how to get my head around it.”

Past, Present, Someday

Humankind has long tried to put our experience of the cosmos into words, imbuing the stars with meaning and purpose. Cosmic introspection has been particularly well documented in the past half century, when space exploration really took off. Astronauts report strong responses to seeing Earth from space, including awe at our planet’s fragility and a sense of connectedness with their fellow humans. Anyone who’s seen the famous Pale Blue Dot photo, which captured Earth as a speck suspended in darkness, might have momentarily felt small and insignificant in the face of the universe. People have felt oddly proud of a drone flying for the first time on Mars, and melancholy when spacecraft run out of power or plunge onto another planet to die.

Adding another dimension—the passage of time—to our contemplation of space produces a uniquely strange sensation. Space and time are, of course, inextricably linked, as Einstein’s theories of relativity show. But when we contextualize these concepts in our own life, we tend to short-circuit—or at least I do. You’re suddenly setting your own life alongside forces that operate on an entirely different scale. You’re not just looking at a pretty picture of, say, the cliffs of the Carina Nebula—someplace you will almost certainly never go. You’re suddenly seeing sharp detail among the vague outlines of the future, and you don’t know how you’ll fit in.

1,929,530times before 2034

1,929,530times before 2034

1,929,530times before 2034

“In a way, it’s horrifying,” David Grinspoon, an astrobiologist at the Planetary Science Institute, told me. Grinspoon will be in his 70s when the NASA spacecraft he’s working on launches to Venus in 2029. “It sort of creeps up on you, and you feel like you’re a much younger age than the calendar would testify to,” he said. But the idea of still working on the project years from now thrills him too: “It’s something to look forward to at a time of life when you might otherwise be possibly filled with a little bit of dread.”

Like Hammel, Grinspoon contributed to the Voyager missions. Every time the machines flew past their targets, the team convened to take in the historic observations together, “almost like high-school reunions, except we were meeting at a different planet each time,” he said. As the mission coasted from Jupiter to Saturn, then to Uranus and Neptune, the people involved felt their own life flying by too. Some mission members retired in the in-between years, and others died. People got married and divorced. They had children. In the almost five years between the Saturn and Uranus flybys, Linda Spilker, a scientist on the mission, became a mother of two; she likes to tell her daughters that they were born when the planets aligned.

You Were Born in

Here’s another. By our calculations, you’ll be

84 years old when a radio transmission from Earth in 1999 reaches its target, a star in the constellation Cygnus.

Here’s another. By our calculations, you’ll be

84 years old

when a radio transmission from Earth in 1999 reaches its target, a star in the constellation Cygnus.

Here’s another. By our calculations, you’ll be

84 years old

when a radio transmission from Earth in 1999 reaches its target, a star in the constellation Cygnus.

Space compels us to imagine ourselves in a future state, a cognitive process that psychologists call “mental time travel,” Dean Buonomano, a neurobiologist and researcher at UCLA who studies how our brains process time, told me. Mental time travel isn’t limited to space. Many earthly endeavors take years or decades to come to fruition—fomenting social change, for example, or even just building new subway lines. “This ability to plan for the long, long–term future, decades and even centuries ahead—it’s uniquely human,” Buonomano told me. But I’d argue that no other form of mental time travel gives rise to the distinct existential vertigo that pondering space exploration does. No human concerns unfold over the scale of billions of years, which is how long it took some of the earliest starlight in the universe to reach the Webb telescope. In forcing us to consider the longest possible arc of our future, space, more than any other domain, connects us with our most vulnerable, most essential qualities.

Not every space expert often stops to contemplate the more emotional aspects of their work. “A lot of academia is about just getting to the next stage—getting the next proposal, getting funding for the next thing, doing the next observation,” says Naomi Rowe-Gurney, an astronomer at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center who studies Uranus and Neptune. (The next missions to these planets won’t come around until the 2040s, or even later.) Rohan Naidu, an astronomer at MIT who is using the Webb telescope to characterize early galaxies, prefers to stay in the moment rather than worry about what new invention will come after the telescope is obsolete. Still, he feels excited about the space-future. “How can you not be optimistic?” Naidu told me. “A hundred years ago, we barely knew that there were other galaxies out there.”

For me, it’s like this: When I think about Dragonfly and 2034, I think about all of the things in my own life that haven’t happened yet, and which will happen—hopefully—by the time I’m 44. I feel optimism, dread, and tenderness for my future self, and that crystallizes, almost paradoxically, into nostalgia. It’s strange to long for a future that hasn’t happened yet, but that’s what space makes me do. A version of this sensation already exists in the literature; psychologists refer to it as “anticipatory nostalgia,” a longing for the present before it has disappeared. Space, I think, adds a certain cosmic sheen. Humanity can plan to put a spacecraft on a distant moon in a particular year, and despite the challenges of spaceflight, we can be fairly confident that the plan will work out. But none of us can predict our own trajectory with the same precision.

Past, Present, Someday

When I ran this nostalgia thing past astronomers, many of them got where I was coming from but didn’t quite feel the same way. Fine, so I’m the biggest sap! At least Lisa Messeri understood me. She’s an anthropologist at Yale who has written about how planetary scientists make the universe meaningful to the general public. Space doesn’t make her feel sappy, but she told me that my reaction is an attempt to transform a vast cosmic scale into a human one. “Everyone has to come up with a way to find meaning against these incomprehensible timescales,” Messeri said.

Perhaps the person best qualified to talk about cosmic introspection is Ann Druyan. She’s not an astronomer, but she helped create the Golden Record, a sort of time capsule of humanity hurtling away from Earth on each of the Voyager probes. The records contain photographs of people, sound bites of weather and wildlife, greetings in dozens of languages, and music—all intended for any alien civilizations who may find them. Druyan herself is in the Golden Record, in the form of brain waves logged while she meditated on love—specifically, her developing love for Carl Sagan, her collaborator on the project. Druyan was 28 when the Voyager missions launched; she is 73 now, and she described her involvement as an exercise in approximating eternity. “I think it liberated me, actually, from my fear of death,” Druyan told me. “My own death feels like a postscript, really, to this event in my life that was so pivotal.”

4,639,780times before Cygnus receives that cosmic call

4,639,780times before Cygnus receives that cosmic call

4,639,780times before Cygnus receives that cosmic call

Cosmic introspection can be an uplifting exercise, assuring us that we have monumental wonders to look forward to, two or 20 years from now. But it’s also a reminder of all the magnificence we won’t live to see. Druyan wishes that Sagan, who died in 1996, could have witnessed a mission like Dragonfly; he was one of the first scientists to hypothesize that Titan has bodies of water that could potentially be conducive to life, and he urged NASA to go there. As for herself, “I don’t even know if I’ll be here in 2034,” Druyan said. “But I know that in 2034, and 2534, and 3034, those Voyagers will still be moving.”

Like Druyan, I can’t know what I’ll be doing when Dragonfly lands, but I can imagine it. I’ll be sitting at my desk, typing up a story about the mission, my back aching more than it used to. And later that night, after I’m done, I’ll go outside. I’ll look up at the night sky, searching for the familiar, sparkling pinpricks of stars and planets, and wonder, Where did all the time go?

Space imagery: Getty