This Month in Physics History – American Physical Society

By Tess Joosse | January 12, 2023

Credit: Elia King / APS. V-2 photograph: Public domain / U.S. Army. V-2 diagram: Public domain / U.S. Air Force.

Before John Glenn, Neil Armstrong, or Sally Ride could step into a spacesuit and rocket into the annals of history, an intrepid bunch of fruit flies had to pave the way.

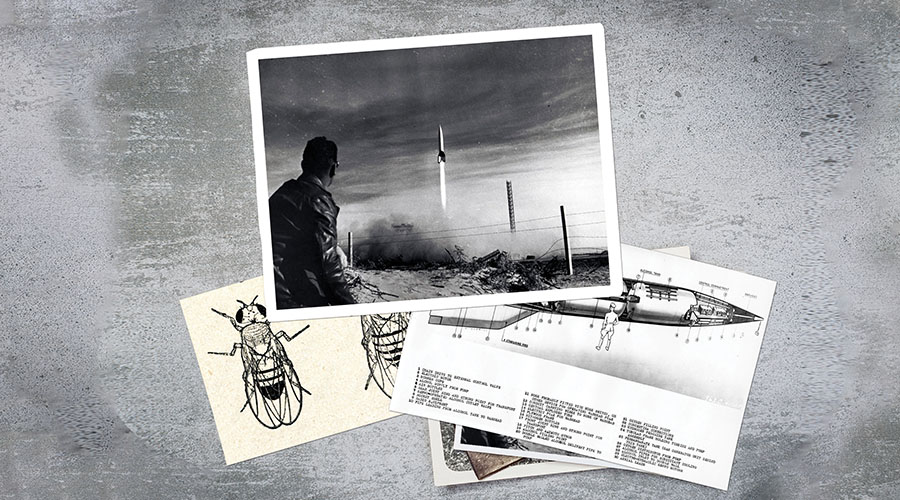

Of course, the flies didn’t have much of a say when they blasted off on a V-2 rocket launched from New Mexico’s White Sands Proving Grounds on Feb. 20, 1947. But as the first animals intentionally shot into and returned alive from space, the insects’ journey heralded a new age in space research and exploration. The flies’ flight traces to the summer of 1945, when a load of German-made V-2 rocket parts arrived at White Sands, a newly established military testing area that is “almost as isolated as a valley of the Moon, which it resembles,” wrote Lloyd Mallan in Men, Rockets and Space Rats, an on-the-ground chronicle of early spaceflight efforts published in 1955. The U.S. also imported a group of scientists and engineers from postwar Germany to assist with experiments using the V-2s, part of the intelligence operation later known as Operation Paperclip.

Standing 46 feet tall, weighing 28,000 pounds, and equipped with a guidance system, the V-2 rocket was the world’s first long-range ballistic missile. As the war ended, both the Soviet Union and the U.S. scrambled to capture V-2 technology and know-how for study and missile development.

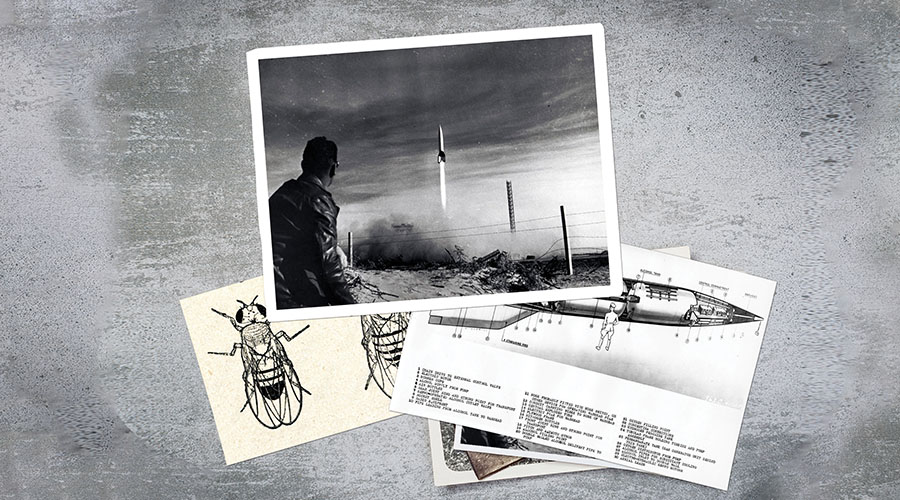

By this time, the fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster) had become a star player in genetic and biomedical research. Kitchen proprietors know them well as the pests that linger around overripe bananas, but for scientists looking for an inexpensive model organism, fruit flies are a dream. “They can be easily cultured and maintained in small lab spaces; they develop from embryo to adult in about ten days; [and] they reproduce by the thousands,” writes Harvard University biologist Stephanie Mohr in First in Fly: Drosophila Research and Biological Discovery.

The humble fruit fly — the first animal sent up in space.

Beyond their ubiquity and usability, fruit flies have simple genomes with only four chromosome pairs, yet are quite like humans in how their traits are inherited, genes are structured, and cells work. Some estimates conclude that nearly 75% of all disease-causing genes known in humans are also found in fruit flies, and to date, at least five Nobel Prizes in Physiology or Medicine have been awarded for research done in the tiny insects.

The second of those five was awarded in 1946, only a few months before the flies’ ride on the V-2, to geneticist Hermann Joseph Muller “for the discovery of the production of mutations by means of x-ray irradiation.” In a series of experiments in 1926 and 1927, Muller found that bombarding flies with x-rays induced mutations in their genes, particularly mutations that were lethal when passed to the flies’ offspring.

Muller’s work dovetailed with concerns over how cosmic radiation from the high-energy particles careening around space would impact a human body. While cosmic rays and x-rays are different, they both expose the body to potentially harmful radiation (today, an astronaut spending a year on the International Space Station is exposed to radiation equivalent to around 900 chest x-rays, according to NASA). “No one can determine the effects of cosmic rays on living cells or tissues without subjecting some of those cells and tissues to radiation,” wrote Mallan. Fruit flies could be easy first test subjects.

When V-2 work began at White Sands, a group of scientists quickly recognized the missiles’ potential for space research, and in early 1946, a panel there began fielding proposals from civilian engineers and researchers. It quickly approved a plan, concocted by scientists from Harvard and the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory, to launch fruit flies and corn seeds on a rocket.

Up they went on Feb. 20, 1947. The flies reached an altitude of 109 kilometers in 190 seconds (space starts at 100 kilometers, according to NASA), then parachuted back down to Earth, where they were recovered alive and examined by biologists. “Analysis made by Harvard on recovered seeds and flies has shown that no detectable changes are produced by the radiation,” wrote U.S. Naval Research Laboratory nuclear physicist Ernst H. Krause in a report published that same year.

In the years after, a parade of rodents, monkeys, dogs, cats, and other animals were launched into space to further study the effects of radiation and other phenomena like microgravity. These animals traveled on both American and Soviet launches and included the first primate in space in 1949, a rhesus macaque named Albert II (the first Albert died during a failed launch in 1948), and the famous mutt Laika, who became the first animal to orbit Earth in 1957. Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first human to go to space in 1961, and American astronauts soon followed.

But even as scientists turned their attention to mammals, the fruit fly work continued. In 1952, the military established the Space Biology Laboratory at Holloman Air Force Base near White Sands to coordinate the animal studies. Mallan writes of how laboratory head Major David Simons spent hours painstakingly transferring flies one by one with tweezers into bottles to send up in rockets. “After you stare enough fruit flies straight in the eye, you start to have hallucinations. I’m beginning to think I can see their eyelashes,” Simons said.

Over the next several decades, studies showed that fruit flies sent to or born in space died earlier, accumulated more genetic mutations, and had damaged sperm and impaired immune systems when compared to earthbound flies. In the 2010s, NASA sent several waves of flies to the International Space Station; when they returned, experiments found that the flies’ hearts had changed shape and were worse at pumping blood. Others revealed that the flies’ central nervous systems were altered by spaceflight, and that artificial gravity helped temper some of the effects.

Today, NASA regulates how much radiation astronauts can receive over their careers. Scientists have recommended the agency revise its guidelines as it looks towards returning humans to the moon in 2025, for the first time since 1972. Researchers are still trying to understand how radiation and low gravity will affect those astronauts. When NASA’s Orion capsule orbited the moon for several weeks this past November and December, two mannequins with radiation monitors embedded in their artificial organs, as well as yeast cells to be studied for genetic mutations, were onboard. This time, the fruit flies were kept on Earth.

Tess Joosse is a science journalist based in Madison, Wisconsin.