On Monday morning, SpaceX launched one of its reusable rockets from Cape Canaveral, Fla., carrying 60 satellites into space at once. It was the second payload of Starlink, its planned constellation of tens of thousands of orbiting transmitters to beam internet service across the globe.

When SpaceX, the private rocket company founded by Elon Musk, launched the first batch of Starlink orbiters in May, many astronomers were surprised to see that the satellites were extremely bright, causing them to fear that the constellation would wreak havoc on scientific research and transform our view of the stars. Since then, many scientists have been on a mission to better quantify the impacts of Starlink and to share their concerns with SpaceX.

In response, SpaceX has said that it wants to mitigate the potential impacts of Starlink. But at the same time, the company is still moving full steam ahead.

In October, Mr. Musk announced that he was using Twitter via a Starlink internet connection, as his company was requesting permission from the Federal Communications Commission to operate as many as 30,000 satellites on top of the 12,000 already approved. Should SpaceX succeed in sending this many satellites to low-Earth orbit, its constellation would contain more than eight times as many satellites as the total number currently in orbit.

That move added to the worries of many astronomers.

When James Lowenthal, an astronomer at Smith College, first saw the train of Starlink satellites marching like false stars across the night sky in the spring, he knew something had shifted.

“I felt as if life as an astronomer and a lover of the night sky would never be the same,” he said.

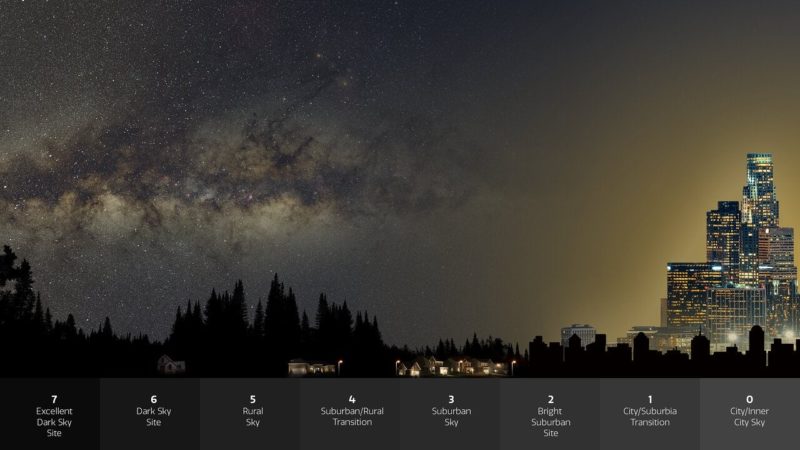

Most of the first Starlink nodes have since moved to higher orbits and are now invisible for most of us who live under bright city lights. But they are still noticeable from places with dark skies. If thousands more of these satellites are launched, Dr. Lowenthal said he feared “it will look as if the whole sky is crawling with stars.”

Since May, the American Astronomical Society has convened an ad hoc committee with Dr. Lowenthal and other experts to discuss their concerns with SpaceX representatives once a month.

At the same time, SpaceX has been working directly with the National Radio Astronomy Observatory, a federally funded research center that operates facilities across the world, to jointly minimize potential impacts of Starlink satellites on radio wavelengths that astronomers use.

But these conversations did not focus on light pollution, a problem presented by the reflective surfaces of proposed satellite constellations such as Starlink. At first, SpaceX said the complication would be minimal, and the new committee is trying to assess the impact and actively find solutions.

“So far, they’ve been quite open and generous with their data,” Dr. Lowenthal said. “But they have not made any promises.”

A spokeswoman from SpaceX said the company was taking steps to paint the Earth-facing bases of the satellites black to reduce their reflectiveness. But Anthony Tyson, an astronomer at the University of California, Davis, said that wouldn’t solve the problem.

Dr. Tyson is the chief scientist for the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope — a 27-foot, billion-dollar telescope under construction in Chile that will scan the entire sky every three days. The survey, the world’s largest yet, will help astronomers better understand dark energy, dark matter, the origin of the Milky Way and the outer regions of the solar system. But because it is designed to scan faint objects, it is expected to be greatly affected by the satellites.

Dr. Tyson’s simulations showed that the telescope would pick up Starlink-like objects even if they were darkened. And they wouldn’t just affect a single pixel in a photograph. When there is a single bright object in the image, it can create fainter artifacts as well because of internal reflections within the telescope’s detector. Moreover, whenever a satellite photobombs a long-exposure image, it causes a bright streak of light that can cross directly in front of an object astronomers wish to observe.

“It’s really a mess,” Dr. Tyson said.

Knowing how challenging it would be to correct these interrupted images, Dr. Tyson decided the best step forward was to set the telescope to avoid Starlink satellites. While simulations based on the earlier 12,000-satellite total suggested that would be possible, SpaceX’s application for 30,000 additional satellites upset the calculations.

“We’re redoing the models now just to see what’s visible at any one time — and it’s really quite frightening,” said Patrick Seitzer, a professor of astronomy emeritus at the University of Michigan, who has been running similar analyses to determine how many satellites will be visible and when.

His preliminary results suggest that avoiding the satellites would be difficult during twilight — a serious problem given that potentially hazardous asteroids and many objects in the solar system are best seen during this time. The satellites thus limit the ability of astronomers to observe them.

And Dr. Tyson’s early simulations also confirm the potential problems, demonstrating that over the course of a full year, the giant telescope wouldn’t be able to dodge these satellites 20 percent of the time. Instead, those images would be effectively ruined.

SpaceX’s 30,000 satellites might also just be the start as other companies, such as Amazon, Telesat and OneWeb, plan to launch similar mega-constellations.

“If there are lots and lots of bright moving objects in the sky, it tremendously complicates our job,” Dr. Lowenthal said. “It potentially threatens the science of astronomy itself.”

Jonathan McDowell, an astronomer at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics who closely tracks objects in orbit, agrees.

“There is a point at which it makes ground-based astronomy impossible to do,” he said. “I’m not saying Starlink is that point. But if you just don’t worry about it and go another 10 years with more and more mega-constellations, eventually you are going to come to a point where you can’t do astronomy anymore. And so let’s talk about it now.”

While astronomers are starting those conversations, they have little legal recourse. There are no regulations in place to protect the skies against light pollution.

“International space law is pretty wide open,” said Megan Donahue, an astronomer at Michigan State University and the president of the American Astronomical Society. While many astronomers have been concerned about radio interference and space debris, she says light pollution is a bigger concern because there are no rules in place. That means any path forward relies on the good will of SpaceX and other companies.

“It’s more of a philosophical question,” Dr. Donahue said. “It kind of boils down to: How much do I trust corporate good will, and how much would a corporation care about the opinion of people who care about science and astronomy?”