Dairy looks to ancient technology to manage manure odor, runoff – vtdigger.org

Sam Dixon, dairy farm manager for Shelburne Farms. Photo by Elizabeth Gribkoff/VTDigger

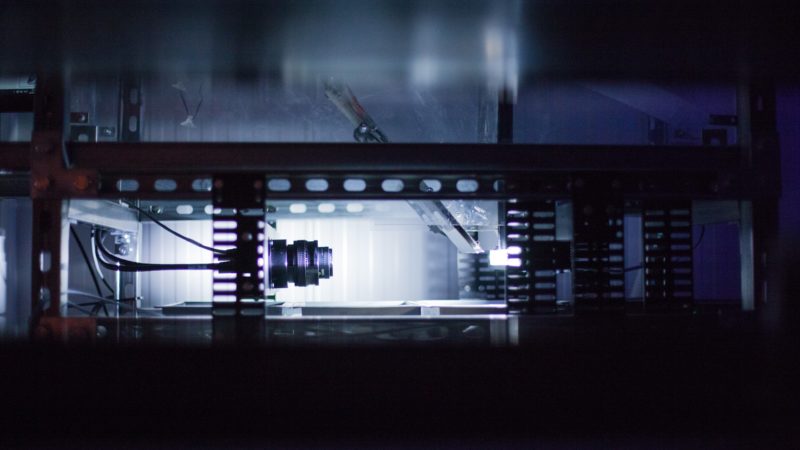

SHELBURNE — A dairy farm in spitting distance of Lake Champlain hopes an ancient technology can cut down on odors from manure, and prevent the nutrient-rich runoff that contributes to pollution in Vermont’s waterways.

At the end of June, Shelburne Farms had a truckload of biochar delivered from Quebec to mix into their 350,000-gallon manure pit.

“It created a crust across the pit and then it was like — immediate odor reduction,” said Sam Dixon, dairy farm manager for Shelburne Farms. Other employees of the non-profit, who likely had more sensitive noses for manure odors, had also noticed the smell go down, he said.

Biochar, which has experienced a recent resurgence in popularity as a potential way to capture carbon in soil, is produced by burning biomass at high temperatures in a low oxygen environment — a process called pyrolysis. The technology is far from new: pre-Colombian civilizations added Terra preta, or dark earth in Portuguese, to low-nutrient Amazonian soils to enhance their fertility.

On a warm early August day, the biochar, which looks like fine charcoal, was visible floating on top of the manure pit at Shelburne Farms. Dixon hopes it will help trap gaseous emissions that could otherwise come off of the manure pit.

“When you smell less, you’re losing less nitrogen,” he said.

Dairies have been experimenting with biochar as a method to reduce odor. A 2017 study published in the Journal of Environmental Quality found that three different types of biochar applied to a manure lagoon reduced odor.

“These results show that biochar covers hold promise as an effective means for reducing odor and gas emissions while (absorbing) nutrients from liquid dairy manure, which in some areas, could mean a dramatic improvement in air quality and the environmental impacts of manure lagoons,” the study authors wrote.

VTDigger is underwritten by:

And another recent study showed that adding biochar to composting manure can cut down on nitrogen emissions from composting manure.

There are also hopes that biochar could help the state tackle the runoff from farms that pollutes Vermont’s waterways.

A cow at the dairy farm at Shelburne Farms. Photo by Elizabeth Gribkoff/VTDigger

Lake Champlain, Lake Memphremagog and Lake Carmi are all under federal pollution reduction orders, or TMDLs, to reduce incoming phosphorus pollution. The agriculture sector has contributed to around 41% of the phosphorus coming into Lake Champlain, according to the TMDL.

Farmers have been implementing a range of practices, including injecting manure, no-till farming and cover cropping, to reduce nutrient runoff. Dairy farms with over 200 cows are now required to have approved nutrient management plans.

Shelburne Farms is not the only Vermont institution looking into biochar for manure management. Last October, Gov. Phil Scott announced six recipients of grants to fund prototypes for phosphorus extraction technologies.

One winner, Green State Biochar, has been producing biochar from wood waste from local mills. The team is experimenting this year with using biochar to treat farm run-off in Cabot and Westfield, with the aim of reusing the nutrient-rich leftovers as fertilizer.

Kaitlin Hayes, agricultural water quality specialist for the state Agency of Agriculture, Food and Markets, said the state evaluation team would review the technologies and business plans in October before selecting one or more to scale up.

At Shelburne Farms, Dixon said he is awaiting samples of the biochar-enhanced manure he sent to UVM to compare to nutrient levels in previous years’ manure. Shelburne Farms uses an aerator machine to poke holes in the ground before spreading manure and has been “spreading less more often” to reduce runoff, he said.

“I think any farm is interested in making better use of the nutrients they’re generating on the farm — so that you buy less stuff in for fertilizer — and in creating a more sustainable system,” said Dixon.

Scientific articles on biochar as a way to capture greenhouse gas emissions have a common theme: small-scale applications show “promising” results, but more research is needed.

“It is important to determine the pyrolysis conditions and feedstock needed to produce a biochar with the desired properties for a specific application,” write the authors of a recent peer-reviewed study on adding biochar to soil.

Some dairy farms in Vermont have installed anaerobic digesters to convert manure into methane to generate electricity. Dixon said Shelburne Farms had been thinking about installing a digester for most of the 23 years he’s worked there, but felt it did not scale down for smaller farms due to the high cost and space needed.

Although biochar has been hailed by devotees as a “win-win,” it is not without its detractors, including Vermont biologist Rachel Smolker, founder of Biofuelwatch.

Smolker and others have expressed concerns that increased demand for biomass could exacerbate deforestation — and that biochar’s supposed ability to capture greenhouse gases is too variable to be counted on.

And a recent meta-analysis of multiple studies found that using biochar as a soil amendment has, on average, “no effect on crop yields in temperate latitudes.”

A manure pit where Shelburne Farms is experimenting with biochar, a pre-Colombian agricultural technique some hope can reduce odors and runoff from dairy farms. Photo by Elizabeth Gribkoff/VTDigger