August Will Have Two New Moons! What’s the Big Deal? – SkyandTelescope.com

First there were “blue Moons;” now there are “black Moons.” What do these terms mean?

If you’ve been keeping your eyes on astronomy news lately, you might have started noticing hype-filled stories telling you to make sure you keep your eyes open in August: “There’ll be two new Moons!” The next new Moon is at 3:12 UT on August 1st, which corresponds to 11:12 p.m. EDT; the second new Moon falls at 10:37 UT on August 30th.

Some of these stories lend the phenomenon a nickname, like “Black Moon.” There’s a better-known term, “Blue Moon,” that has been around for decades. While its exact definition is debated, these days it usually means the second full Moon in a month. A more old-fashioned definition defines it as the third of four full Moons, like the Blue Moon of May 2019.

Two new Moons in a month, though — that’s the opposite of a Blue Moon. So what’s the big deal about a Black Moon? Or is it a big deal at all?

Defining a Month by the Moon

Astronomers measure months in several ways. For instance, a sidereal month is the time the Moon takes to make one orbit around Earth, relative to the background stars. Meanwhile, an anomalistic month is the time between lunar perigees, the Moon’s closest point to Earth. These are about 27.5 earth days. But the lunation, or synodic month, is what most of us talk about when we talk about months: That’s the amount of time it takes to go back to a phase, usually from new to new.

Having two full — or new — Moons in a month is uncommon but not rare. A lunation is about 29.5 days, and there are 365.25 days in a year. So, on average, there are slightly more than 12 full lunar cycles a year. This means about every two and half years (2 years, 8 months, roughly speaking) there’ll be two full or two new Moons in a given month.

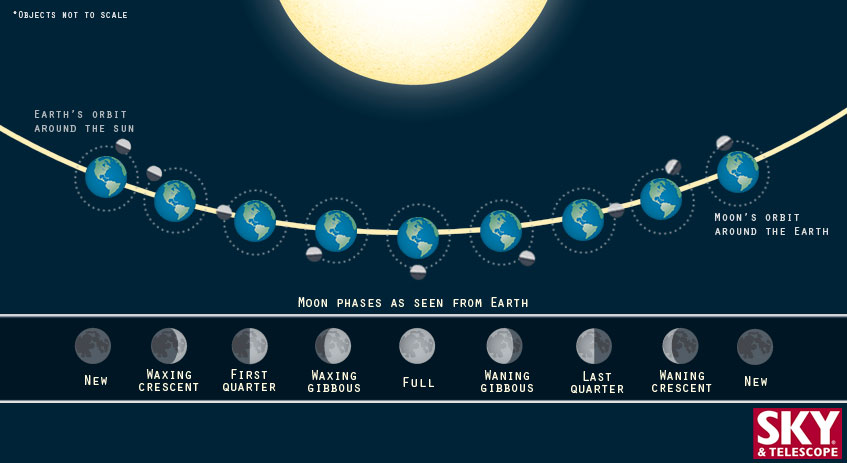

We see the Moon go through a changing cycle of phases each month due to its orbital motion around Earth and the changing geometry with which we view it.

Ana Aceves / Sky & Telescope

Let’s take a bigger view, though. Since a 29.5-day lunar cycle is shorter than every month except February, in every year every month except February is likely to have a repeated phase.

Put differently, phases correspond to places in the Moon’s orbit. So when the Moon finishes a lap and returns to the same spot in its orbit around the Earth every 29.5 days, it’s also at the same phase. So at the end of most months, the Moon is likely to come back to the spot it was in at the beginning of a month. Just like that, there’s a repeated phase in every month!

For example, let’s take a look at the upcoming year (dates are listed in UTC time zone):

August: New Moon on the 1st and 30th.

September: Thin, waxing crescents on the 1st and 30th.

October: Waxing crescents on the 1st and 31st.

November: Waxing crescent on the 1st & 30th.

December: Waxing crescent on the 1st & 31st.

January 2020: Waxing crescent on the 1st & 31st.

February 2020: Not enough days for a full cycle, even though it’s a leap year. No repeating phases.

March 2020: Nearly first-quarter crescents on the 1st and 31st.

April 2020: First quarter on the 1st and 30th.

May 2020: Waxing gibbous on the 1st and 31st.

June 2020: Waxing gibbous on the 1st and 30th.

July 2020: Waxing gibbous on the 1st and 30th.

August 2020: Just-about-full-waxing gibbous on the 1st & 31st.

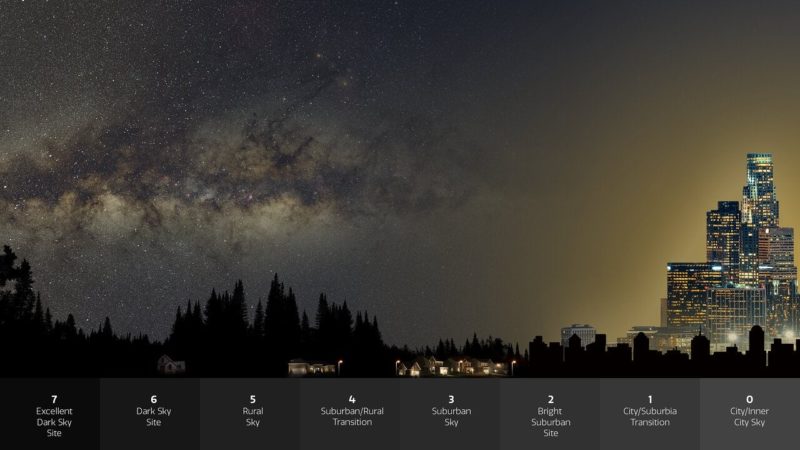

So, what happens if there’s a second new Moon? Not much. A second new Moon in a month can help with skygazing, because there’s no moonlight to wash out the stars. But it’s hard to get excited otherwise. After all, the new Moon lies between the Sun and Earth, and since all of the Sun’s light is hitting the lunar far side, there’s nothing to see!

You might see news stories that try to acknowledge this. But they’ll fumble and say that the Moon will be invisible to us at nighttime: “Second New Moon in Tonight’s Sky!” Nope. New Moons rise and set with the Sun, so they’re up in the daytime, not at night.

Besides, since the new Moon is up during the day when clear skies are blue, wouldn’t it be ironic if we called new Moons Blue Moons?

Better yet, let’s stay clear of the hype, enjoy the night sky, and watch another lunation unfold before our eyes.