NASA to consider WFIRST launch options after mission passes key review – Spaceflight Now

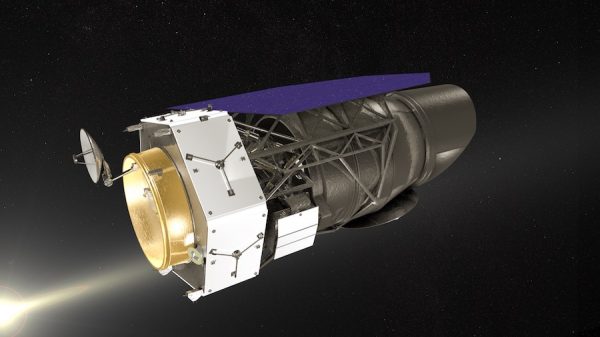

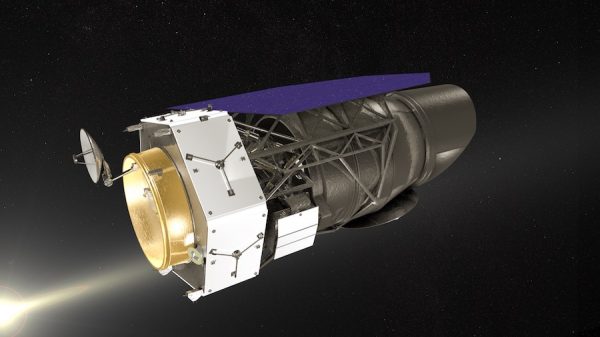

NASA expects to select a launch vehicle next year to carry the Wide Field Infrared Survey Telescope — a multibillion-dollar flagship astrophysics observatory targeted for cancellation by the Trump administration — into space in 2025 after the mission passed a key review last month, agency officials said.

WFIRST is NASA’s next flagship-class astronomy mission after the James Webb Space Telescope, which is scheduled for launch in 2021 after years of delays and ballooning costs.

JWST will launch on a European Ariane 5 rocket from French Guiana, part of the European Space Agency’s contribution fo the mission. WFIRST will launch from Cape Canaveral on a U.S. rocket, likely provided by SpaceX, United Launch Alliance, or Blue Origin.

NASA managers in late February approved WFIRST to proceed into full development in preparation for launch targeted in October 2025. The space agency is continuing with development of WFIRST despite attempts by the White House to cancel the project.

Officials said last week that NASA intends to select a launch provider for the mission in 2021, rather than in 2023 as originally planned.

The Trump administration targeted WFIRST for termination in its fiscal year 2019 and 2020 budget proposals, but Congress appropriated $312 million and $510 million for the mission in the final budgets for 2019 and 2020. In the White House’s fiscal year 2021 budget request last month, officials again sought to cancel development of WFIRST “to focus on higher priorities.”

The White House also proposed zero funding in 2021 for SOFIA, an airborne infrared observatory jointly managed by NASA and DLR, the German space agency.

The overall NASA budget proposal from the White House requests $25.2 billion for the space agency in fiscal year 2021, which begins Oct. 1. That’s nearly 12 percent more than NASA’s enacted budget for fiscal year 2020.

“It’s a great budget for NASA. It’s a great budget for NASA science, but it’s not such a great budget for astrophysics,” said Paul Hertz, director of NASA’s astrophysics division, during a March 5 meeting of the agency’s Astrophysics Advisory Committee.

Assuming Congress again denies the White House’s proposal to cancel WFIRST, work will continue to ready the mission for launch in October 2025.

Using a 7.9-foot (2.4-meter) primary mirror provided to NASA by the National Reconnaissance Office, the U.S. government’s spy satellite agency, WFIRST will be sensitive to faint infrared signals across the sky. Major objects of study during the WFIRST mission will include dark energy — the mysterious force driving the accelerating expansion of the universe — and exoplanets, or planets around other stars.

The 2.4-meter primary mirror is the same size as the mirror on the Hubble Space Telescope, giving WFIRST similar sensitivity. But NASA says WFIRST will have a viewing area 100 times larger than Hubble.

“WFIRST’s design already is at an advanced stage, using components with mature technologies,” NASA said in a March 2 statement. “These include heritage hardware — primarily Hubble-quality telescope assets transferred to NASA from another federal agency — and lessons learned from NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope – the agency’s flagship infrared observatory, targeted for launch next year.”

A wide field instrument and coronagraph instrument will fly on the WFIRST mission.

The wide field instrument, essentially a giant 300-megapixel camera, will help astronomers map the presence of dark matter and the influence of dark energy across the universe. The camera will also help astronomers study exoplanets in our own galaxy.

WFIRST’s coronagraph will block out the light of stars, allowing the telescope to directly image exoplanets.

With the completion of the WFIRST confirmation review last month, officials are proceeding with the detailed design of the spacecraft, telescope and instruments.

The confirmation review also clears the way for NASA to procure a launch vehicle for WFIRST. NASA typically awards a launch contract for the agency’s science missions around two-and-a-half years before liftoff, but officials plan to select a launch provider for WFIRST nearly five years ahead of time, according to Jeff Kruk, the mission’s project scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.

Because they do not yet know what rocket will carry WFIRST into space, engineers are designing the mission for the acoustic, vibration and load environments of three launchers projected to be available in 2025.

“Right now, we’re carrying three launch vehicles,” Kruk said. “We have all our mechanical environments and envelope environments for those three vehicles, and each one happens to drive a diff parameter. One drives the acoustics, one drives the random vibe (vibration) environment, one drives the actual loads environment. So this makes the design challenging.”

NASA’s Launch Services Program at the Kennedy Space Center, which procures launch services for NASA science missions, will select rocket for WFIRST next year.

“The Launch Services Program at the Cape has agreed to start this process almost twice as far ahead as they normally do,” Kruk said March 5. “They plan to do an early acquisition and actually award the contract almost five years ahead of launch, instead of two-and-a-half (years), so that’s great.”

Knowing WFIRST’s launch provider sooner will allow allow engineers to design the mission for one vehicle, rather than ensuring it can be accommodated by three rockets.

Engineers last year completed an analysis of the loads WFIRST would experience during launch on a SpaceX Falcon Heavy rocket, Kruk said. Similar analyses using predicted loads data for ULA’s Vulcan Centaur rocket and Blue Origin’s New Glenn launcher will be performed soon, according to Kruk.

Mission managers are no longer considering launching WFIRST on NASA’s heavy-lift Space Launch System, Kruk said.

The WFIRST team will build engineering test units and models over the next year to verify the observatory’s design. A critical design review is scheduled in mid-2021 to finalize the design ahead of full-scale fabrication of the mission’s spacecraft, telescope and instrument components.

The primary mirror for WFIRST is being modified from its original spy satellite design at L3Harris Technologies in Rochester, New York.

NASA formally started development of the WFIRST mission in 2016 after several years of preliminary studies and technology maturation work. The initial concept for WFIRST called for the observatory to use a smaller telescope, but NASA upsized the observatory to employ a larger Hubble-sized primary mirror left over from an NRO spy satellite program.

The increasing scale of the observatory caused its predicted cost to swell over a $3.2 billion cap in development costs, and its mass swelled to more than 16,000 pounds (7.3 metric tons), according to an independent technical, management and cost review panel established by NASA in 2017.

NASA managers directed the WFIRST team to trim the mission’s development cost to fit under the $3.2 billion limit by incorporating additional international contributions, and simplifying the observatory’s assembly and ground test campaign before launch.

Some of the stringent requirements for WFIRST’s coronagraph were relaxed after NASA reclassified the instrument as a technology demonstration payload.

NASA says the mission is now predicted to cost around $3.2 billion to develop, but that figure does not include the coronagraph instrument or costs to operate WFIRST for its planned five-year mission after launch. The total cost of the project to NASA, including operations and the coronagraph, is $3.934 billion.

The James Webb Space Telescope’s current development budget is $8.8 billion, with a total mission cost to NASA of $9.66 billion. That does not include contributions from ESA or the Canadian Space Agency.

WFIRST will be positioned in an orbit around the L2 Sun-Earth Lagrange point nearly a million miles (1.5 million kilometers) from Earth, home to JWST and other astronomical observatories.

NASA has already spent about one-third of WFIRST’s projected cost, said Hertz, director of the agency’s astrophysics division.

“We’re not just getting started,” Kruk said. “It’s not just preliminary. We’re very far on our way.”

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.