Astronauts capture SpaceX cargo capsule with robot arm for final time – Spaceflight Now

For the final time, a SpaceX Dragon cargo capsule approached the International Space Station Monday for capture with the research lab’s robotic arm, delivering more than 4,300 pounds of food, experiments and spare parts. Future Dragon resupply missions will use a new spaceship design to automatically dock with the space station.

The unpiloted cargo freighter completed a two-day pursuit of the space station Monday with an automated approach to the orbiting research outpost.

After moving into position less than 40 feet (12 meters) below the station, the Dragon capsule halted its approach and astronaut Jessica Meir took control of the research lab’s Canadian-built robotic arm. Meir, assisted by crewmate Drew Morgan, captured the Dragon spacecraft at 6:25 a.m. EDT (1025 GMT) Monday, more than a half-hour ahead of schedule.

Meir grappled the gumdrop-shaped cargo capsule as the station soared 262 miles (421 kilometers) over the Pacific Ocean northwest of Vancouver, British Columbia.

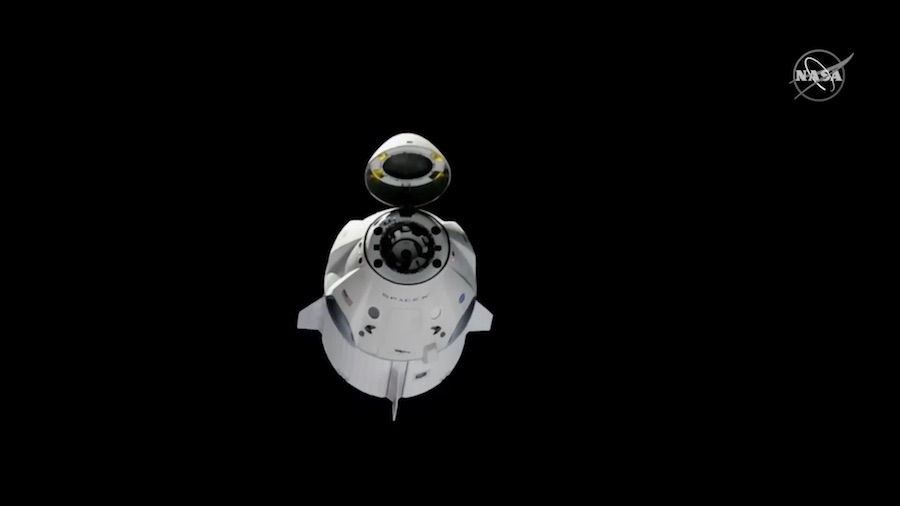

The successful supply deliver marked the 20th time a SpaceX Dragon cargo capsule has arrived at the space station since May 2012. The mission, known as CRS-20 or SpaceX-20, also the final flight of SpaceX’s first-generation Dragon spacecraft, which the company is retiring in favor of a new Dragon capsule designed to dock directly with the space station without needing to be captured by the robotic arm.

“The SpaceX-20 mission is a milestone for several reasons,” Meir said moments after using the robot arm to capture the Dragon spacecraft Monday. “It is, of course, the 20th SpaceX cargo mission, but it is also the last SpaceX cargo vehicle captured by the Canadarm as future vehicles will automatically dock to the space station.”

Capture confirmed! For the final time, a SpaceX Dragon capsule has been captured using the space station’s robotic arm.

Future Dragon missions will dock directly with the International Space Station. https://t.co/M7Kr3vTkCN pic.twitter.com/oTaWBolc23

— Spaceflight Now (@SpaceflightNow) March 9, 2020

The Dragon cargo ship that arrived at the space station Monday is flying in space for the third time. It previously flew to the station on the CRS-10 and CRS-16 missions in February 2017 and December 2018, according to SpaceX.

“This is actually the third time that this specific Dragon capsule has arrived here at station, demonstrating the more sustainable approach that will be paramount to the future of spaceflight,” Meir said. “We welcome SpaceX-20 and are eager to reveal its bounty of science and space station hardware and supplies. Congratulations to SpaceX and all of the ISS partner teams involved.”

The Dragon capsule launched Friday night from Cape Canaveral aboard a Falcon 9 rocket.

The current mission is SpaceX’s last flight under a $3 billion contract NASA awarded the company in December 2008. The Commercial Resupply Services, or CRS, contract was intended to ensure the space station continued receiving regular cargo shipments after the retirement of the space shuttle, which occurred in 2011.

With the delivery of this mission’s cargo load Monday, SpaceX has carried more than 94,000 pounds (about 43 metric tons) to the International Space Station on 20 missions. Assuming the current mission ends successfully next month, 20 Dragon missions will have returned about 74,000 pounds (33 metric tons) of cargo from the space station back to Earth.

Items packed into the Dragon capsule that arrived at the space station Monday include an outdoor science deck to be installed outside the research lab’s European Columbus module. The external platform, named Bartolomeo, will be attached to the outer hull of the Columbus module later this month, and astronauts will perform a spacewalk in April to connect wiring harnesses to bring the new facility into use.

The Bartolomeo platform features 12 different mounting sites to accommodate science payloads, experiments, and technology demonstration packages. Developed by Airbus Defense and Space in partnership with the European Space Agency, the new facility adds to the space station capacity for research, and is aimed at offering accommodations for commercial experiments outside the orbiting complex.

The Dragon spacecraft is packed with about a ton of scientific experiments in its pressurized cabin, including biological research investigations studying microgravity’s impact on stem cells, intestinal diseases and chemical reactions.

Another experiment delivered to the space station comes from Delta Faucet, which will study water droplet formation in microgravity in hopes of developing better-performing shower heads while reducing water usage.

The Dragon spacecraft also carries spare parts and replacement hardware for the space station’s research facilities and life support systems. Components carried on the Dragon capsule include upgraded hardware for the station’s urine processing system, which converts human waste into drinking water.

The new components will allow NASA teams to test out modifications designed to extend the lifetime of the urine processing system’s distillation assembly ahead of future missions to the moon and Mars, which will require longer-lasting life support equipment.

Here is a breakdown of the Dragon capsule’s cargo load:

- Science Investigations: 2,116 pounds (960 kilograms)

- Unpressurized Cargo (Bartolomeo): 1,032 pounds (468 kilograms)

- Crew Supplies: 602 pounds (273 kilograms)

- Vehicle Hardware: 483 pounds (219 kilograms)

- Spacewalk Equipment: 123 pounds (56 kilograms)

- Computer Resources: 2 pounds (1 kilogram)

After about a month in orbit, astronauts will load research specimens and other cargo tagged for return to Earth into the Dragon spacecraft, which is scheduled to depart the space station and splash down in the Pacific Ocean southwest of Los Angeles on April 6.

The return of the Dragon capsule next month will mark the transition to SpaceX’x next CRS contract with NASA. SpaceX’s following series of cargo missions will use a new Dragon spacecraft design known as the Dragon 2. Cargo flights to the space station using the Dragon 2 spacecraft are scheduled to begin in late October.

The Dragon 2’s human-rated variant is named the Crew Dragon, which is scheduled to fly astronauts to the space station for the first time in the coming months.

The first-generation version of the Dragon spacecraft debuted in 2010 with a test flight in low Earth orbit. The Dragon capsule accomplished its first trip to the International Space Station in May 2012 on a second demonstration mission under NASA’s Commercial Orbital Transportation Services, or COTS, program.

Through the COTS program, NASA contributed $396 million toward the development of the Dragon spacecraft and Falcon 9 launcher in a public-private partnership with SpaceX. NASA says SpaceX contributed roughly $450 million to the effort.

With the COTS demonstrations accomplished, SpaceX began regular cargo transportation services to the space station in October 2012 under the CRS contract. In 2014, SpaceX won a NASA competition to develop an upgraded Dragon spacecraft to ferry astronauts to and from the station.

The commercial cargo and crew transportation agreements were designed to give NASA a way to get astronauts, experiments, space parts and other equipment to the space station after the retirement of the space shuttle in 2011.

Northrop Grumman is NASA’s other commercial cargo transportation provider, and Boeing joined SpaceX as the other contractor the commercial crew program.

Since the initial contract award in 2008, NASA has extended the CRS agreement with SpaceX from 12 missions to 20 flights.

The Dragon capsule itself has performed well on all its missions, successfully reaching the space station and returning to Earth on all but one flight. A Falcon 9 rocket failed during launch on a resupply flight in June 2015, destroying a Dragon spacecraft and its cargo load.

SpaceX launched its last new first-generation Dragon spacecraft in August 2017. Since then, the company has reused Dragon vehicles that were refurbished after splashing down in the Pacific Ocean.

NASA awarded a second Commercial Resupply Services contract to SpaceX in 2016. Orbital ATK — now part of Northrop Grumman — and Sierra Nevada Corp. also received CRS-2 contracts to resupply the space station through the mid-2020s.

Northrop Grumman launched its first CRS-2 mission using upgraded versions of its Antares rocket and Cygnus supply ship last November, and Sierra Nevada’s Dream Chaser space plane is scheduled to fly to the space station for the first time in 2021.

The Dragon 2 has a different aerodynamic shape than the first-generation Dragon, and it has body-mounted solar arrays to generate electricity, replacing the extendable wings on the first version of the Dragon spacecraft.

It can also dock automatically with the space station, without requiring station crews to capture it with the research lab’s Canadian-built robotic arm. That means Monday’s arrival of the cargo capsule was the final time a Dragon spacecraft will be robotically berthed to the orbiting complex.

“One of the things we’ll have with CRS-2 (with SpaceX) is we’ll have a little bit more powered payload locker capability,” said Kenny Todd, NASA’s manager of International Space Station operations and integration. “That’ll help us be able to put on more payloads. A lot of the high-value science we fly is associated with some off our biological samples, and our ability to fly more of those allows us to support more users here on the ground with a lot of investigation in the biomedical area.”

The cargo version of Dragon 2 will launch without seats, cockpit controls and other life support systems required to sustain astronauts in space. The cargo version will also launch without the SuperDraco escape thrusters fitted to human-rated Dragon capsules.

While SpaceX and NASA do not initially plan to reuse Dragon 2 capsules for crew missions, the cargo variant will be qualified to fly to the space station and back to Earth up to five times, officials said. The first-generation Dragon capsule was capped at three missions.

Beginning with the CRS-21 mission late this year, the new Dragon 2 cargo capsules will splash down under parachutes in the Atlantic Ocean east of Florida, rather than the current recovery zone in the Pacific Ocean west of Baja California. It takes a day or two for Dragon capsules to get back to port in California on SpaceX recovery ships. That transit time will be cut with splashdowns in the Atlantic.

“When they do that, they’ll be a matter of hours from the port,” Todd said. “So that will allow us to get this critical science back in the investigators’ hands much quicker.”

The Dragon 2 will be able to carry more cargo to the space station. But the Dragon 2’s primary arrival mode, using docking rather than capture and berthing with the robotic arm, comes with a limitation.

The hatches through the space station’s docking ports are narrower than the passageways through the berthing ports currently used by Dragon cargo vehicles.

Northrop Grumman’s Cygnus supply ship and Sierra Nevada’s Dream Chaser space plane are designed to berth to the space station, offering transportation for bulkier items.

Counting the test flights and the failed launch, SpaceX has launched 22 missions using the first-generation Dragon spacecraft.

When the first Dragon capsule launched on a demonstration flight in 2010, it marked just the second flight of SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket. The Falcon 9 is now a workhorse for NASA, the U.S. military and commercial satellite operators, and Friday night’s mission was the 82nd flight of a Falcon 9 rocket since 2010.

SpaceX has matured from a new entrant in the launch industry to a market leader in the decade of Dragon. The company has started regularly reusing rocket boosters and space capsules, and is on the cusp of launching astronauts for the first time.

“We learned so many things,” said Hans Koenigsmann, SpaceX’s vice president of build and flight reliability, during a press conference Friday. “We learned how to operate a spacecraft. We learned how to dock and berth with the station. We learned how to work with NASA, with (mission control in) Houston in parallel, how to do all of these things in order to become basically a space operator.

“There are so many lessons — how to recover it in the ocean, how to refurbish it, and how to make it safe to fly again,” he said.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.