Archivists learn how to preserve audiovisual collections despite time, technology and tragedy – IU Newsroom

There was no power. Darkness fell early. And it was getting cold.

Fifteen hundred media items lay awash in the saltwater brine left behind by Hurricane Sandy in 2012. They were the creative output of 15 years of work at New York City’s Eyebeam, an organization that hosts fellowships and residencies to give artists and technologists space and time to produce their work.

Eyebeam put out an S.O.S. for anyone who knew how to rescue videotapes, CDs, DVDs, data tape and much more from post-hurricane conditions. It’s a relatively rare skill set, but Kara Van Malssen and several colleagues had it in spades. As a graduate student, Van Malssen had helped recover media items damaged by Hurricane Katrina. She showed up again and spent three days leading a group of volunteers through the darkness, cold and muck to retrieve and stabilize Eyebeam’s collection.

Van Malssen prefers to teach people to avoid such situations, but because she knows that’s not always possible, she also shares how to handle the aftermath. She had another opportunity to share her experience during the first Biennial Audio-Visual Archival Summer School held at Indiana University in May.

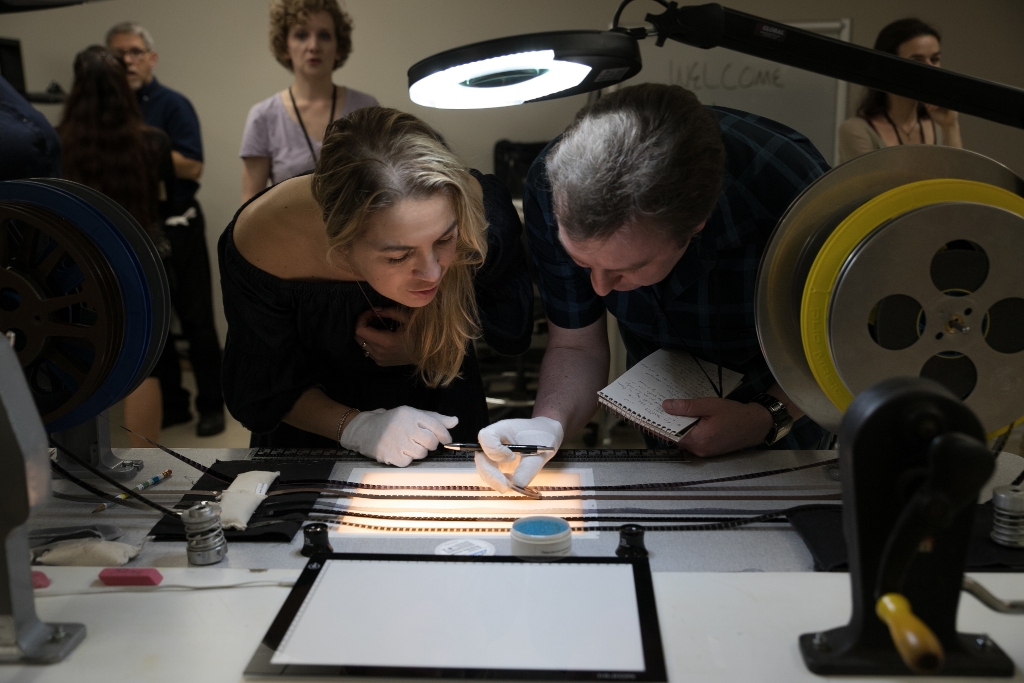

Fifty participants from archives and institutions all over the world were selected to attend the two-week conference, which covered everything an archivist would need to know about handling an archival collection. Experts in the field from all over taught preservation, cataloging, digitization, copyright and more.

The Biennial Audio-Visual Archival Summer School was structured with lectures every morning and hands-on workshops every afternoon, many of them repeated so participants could get the most out of their conference experience. Participants were given one-on-one time with trainers so they could ask specific questions. The summer school also offered several evening film screenings that included restored films, films that showed reuse of archival films and films that told a preservation story. The summer school was an initiative of the IU Libraries Moving Image Archive, in partnership with the International Federation of Film Archives and the Coordinating Council of Audiovisual Archives Associations.

Van Malssen’s disaster recovery workshop was a group favorite. She simulated a burst pipe in her workshop and threw some salt packets in for added yuck factor. She treated participants like volunteers who’d been brought in to deal with the mess. By day’s end, they had gone through a miniature recovery effort and been taught how to better prepare for disasters.

“I have a passion for disaster preparedness,” Van Malssen said. “It’s one of those topics nobody thinks about till it’s time or it’s too late. In the collection management profession, I think it’s something that should be at the forefront of people’s minds.”

The work of archivists can vary — some manage the preservation of entire collections, some are librarians with a focus on digitization and cataloging, and still others are artists with a penchant for preserving history. Not many have had the opportunity to learn all the skills they need to work with audiovisual media.

“Archival expertise has largely fallen away, and the knowledge resides in an increasingly aged core of former film technicians and laboratory works and filmmakers,” said David Walsh, the training and outreach coordinator for the International Federation of Film Archives. “It’s very hard for anyone joining an archive to actually gain this knowledge, so there was a feeling that we needed to have a biennial summer school that addressed the core elements of archiving. This course is about preservation, cataloging, infrastructure, digitization and all the core day-to-day stuff the archives have to deal with.”

Cat Phan, a digital and media archivist for the University of Wisconsin Archives, found the conference to be invaluable for her needs. Her job is to care for image media, including film and audiovisual materials, plus born-digital content. Her current priority is stabilizing the archive’s film collection. Many of the films suffer from vinegar syndrome, which occurs when acetate-based films degrade and exude acetic acid. It is both ruinous and contagious.

“I’m the only one who works with these materials in our department, so even though there are other resources on campus, there’s no one else in our department who has expertise or knowledge about how to deal with any of these formats,” Phan said. “You usually don’t get this sort of training in library professional programs. I didn’t have any internship or practicum experience, either, so I really just wanted a program that was looking at all the issues that AV archivists deal with.”

Time and change have become some of the biggest threats to audiovisual collections. With motion picture imaging dying away in its traditional form, conventional film has already reached the end of its life. Other media, such as videotapes and audiocassettes, will soon follow. It’s the archivist’s job to protect and preserve those formats, and the content they hold, as much as possible.

“Time is against us,” said Natalie Rose Cassaniti, an assistant conservator at the State Library of New South Wales, Australia. “There are massed collections all over the world, but we are limited with time and funding resources to be able to preserve them. While we are maximizing our efforts to capture content, we are at risk of losing many of our culturally significant collections.

“The obsolescence of playing equipment is also a problem, as is the ongoing maintenance of analog and digital collections. You can’t just digitize it and put it away. You have physical objects, which are going to need ongoing care, and once digitized, you also have files that need storage, security and disaster preparedness plans. The fact that technology is so rapidly developing means you also need to continue to migrate digitized content to the latest format.”

Funding is another factor in the struggle to save aging media and their content. Not all countries have the money to fund archives and their services, and those that do have the money aren’t always able to allocate enough to it. Case in point: At the Biennial Audio-Visual Archival Summer School, a group from Australia learned from Van Malssen that the closure of the only lab in their country that was able to rewash film following a flooding incident could be devastating to a film collection.

Indiana University is one of the rare exceptions in the archival world, with its decades-long track record of providing the resources, expertise and funding to preserve and provide access to its unique image and sound collections across all its campuses. In 2013, the university announced it would be allocating $15 million to the Media Digitization and Preservation Initiative to digitally preserve and provide access to all significant audio, video and film recordings by 2020. That’s 325,000 audiovisual pieces. In 2017, the initiative added the digitization of 25,000 film reels to its goal.

“The amazing facilities, staff and ongoing programs that IU has supported allowed us to host the BAVASS program,” said Rachael Stoeltje, director of Indiana University Libraries Moving Image Archive and one of the lead organizers of the summer school. “The development of the Moving Image Archive, the new IU Auxiliary Library Facility addition that boasts a 38-degree vault for motion picture film and the MDPI project: These commitments exhibit a unique devotion to preserving our cultural heritage.”

One of the conference organizers’ goals was to help attendees build a community, so they could consult one another after they went home. For the year following the summer school, participants and trainers will have the opportunity to meet online and discuss successes and challenges at their home institutions.

“What we don’t particularly want to do is parachute in, do two weeks of training and then disappear,” Walsh said. “Continuing professional development is a big challenge because there are no training courses in film archive work apart from what we’re putting on and a few other people around the globe.

“As we move on from this point, there’ll be less and less expertise, less and less equipment, and more degradation, so it’s getting a bit critical. In terms of the media and the expertise, we’re reaching a point where unless people really act now, they’re going to lose large swathes of their cultural heritage.”

Amanda Chambliss is a communications project manager and writer for the Office of the Vice President for Information Technology.