There’s no substitute for Earth, astronomer says – Yale Climate Connections

When news about global warming is grim, some people gaze into the sky and wonder whether humans could find another planet to live on.

Debra Fischer is an astronomy professor at Yale University. She has spent her career searching the stars for other planets.

“My research, my job, is to find planets orbiting other stars,” she says. “And I often get the comment, ‘Oh, good, you’ve just found another planet that we can go to.’ And I want to emphasize that there is no planet B for us.”

She says that astronomy helps her understand just how precious – and vulnerable – this planet is.

“We really do, I think, as astronomers appreciate the fact that the Earth has this incredibly thin veneer of atmosphere,” she says, “and it’s easy to pollute.”

Fischer helps lead a group called Astronomers for Planet Earth. It’s made up of astronomy scientists, educators, and students who have pledged to fight climate change.

They’re working to educate the public about global warming and the urgent need to protect Earth, our home and the only planet we can live on.

“We just need people to come together and solve this problem,” she says.

More from our interview with astronomer Debra Fischer

Editor’s note: Debra Fischer made a number of fascinating comments in our interview with her, but we couldn’t fit them all into our radio segment. See below for more of her remarks, which have been condensed and lightly edited for clarity.

Sarah Kennedy, Yale Climate Connections: Can you describe for me what you see as the unique perspective that astronomers bring to the issue of climate change?

Debra Fischer, Department of Astronomy, Yale University: When astronomers or astronauts go out and explore the universe or the solar system, the first thing that they always do is turn back and look at our home planet. It’s poignant and really quite beautiful that we have images of the Earth which were taken in the 1960s by the Apollo astronauts, and we have a picture of the Earth which was taken by Voyager 1 just as it was leaving the solar system. Carl Sagan convinced the NASA engineers to turn the spacecraft around and take a picture of Earth, a pale blue dot. And that perspective of Earth as this fragile, tiny little “mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam” of scattered light is so haunting and incredible.

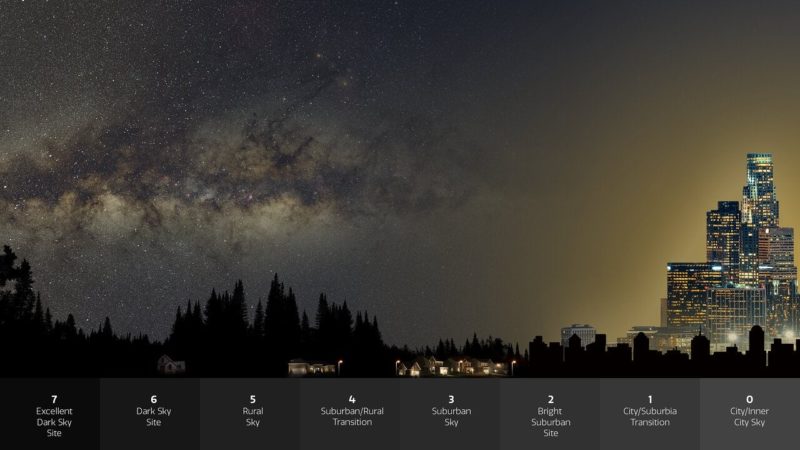

We really do, as astronomers, appreciate the fact that the Earth has this incredibly thin veneer of atmosphere and that it’s easy to pollute. It’s easy to understand how the millions of tons of carbon that we’re putting into the atmosphere are polluting it and causing problems.

The other thing I would add is that my research, my job, is to find planets orbiting other stars. And I often get the question or the comment, “Oh good, you’ve just found another planet that we can go to.”

I want to emphasize that there is no Planet B for us. There is, in the foreseeable future, no way to transport humanity to any of the nearby star systems.

YCC: Are there any other misconceptions about climate change that you think that astronomers are in a particularly good position to correct?

Fischer: So the one thing that’s very interesting is the idea that companies like SpaceX or Blue Origin are planning to set up colonies, human habitats, on Mars or perhaps the moon.

So if people think that going to Mars is a solution, then astronomers are in a good position to remind them that Mars once had running water on its surface. It once had an atmosphere. It may have once had a global magnetic field that protected the atmosphere from the solar wind – but no more is in that state. So Mars, in some sense, is probably a dead planet – a planet where perhaps life existed at one time but because the planet itself is so small it didn’t have enough mass to hang onto its atmosphere and the atmosphere was lost.

If humans go to Mars, and I think that they will, I think that there will be some sort of a habitat that’s established there and it will be incredibly exciting. There’s no way to lift 7 billion people off of planet Earth and put them on a planet that is so much smaller than the Earth and that does not have the resources to support them. Mars is exciting but that’s not the future for humanity.

The other planet that’s really interesting in our solar system is Venus. When the Earth and Venus were forming, at that time Venus would have been very much like the Earth. Venus could very well have had oceans, could have had land masses, and even some kind of life.

But Venus is sort of an accelerated case of climate change. Venus was closer to the sun and so the sun was driving a lot of water into the atmosphere. Water is an incredibly effective greenhouse gas. Carbon dioxide was also coming out of the continents of Venus and so together those formed an incredible greenhouse around Venus and caused Venus to go into what’s called a positive feedback loop. So the hotter Venus got, the more water evaporated, the stronger the greenhouse gases, the more water evaporated. It just keeps going in this sort of doomed cycle.

YCC: What gives you hope?

Fischer: We’re an incredibly precious species. Of all the species that have lived on Earth and then gone extinct, we are the only species that has figured out that the universe began with the Big Bang. We understand that there are planets orbiting other stars. We know that every molecule in our body was forged in the core of a star. Think how magnificent that is – that we’ve figured these things out!

We understand the science of climate change very well, which means we understand how to deal with it. So what gives me hope is watching the young people today. The students that are in my class, they care and they’re passionate and they’re activists on this issue. And I think it’s just a matter of time.

Reporting credit: Sarah Kennedy/ChavoBart Digital Media.