Hubble Sheds Light on Dark Matter and Cosmic Expansion – Sky & Telescope

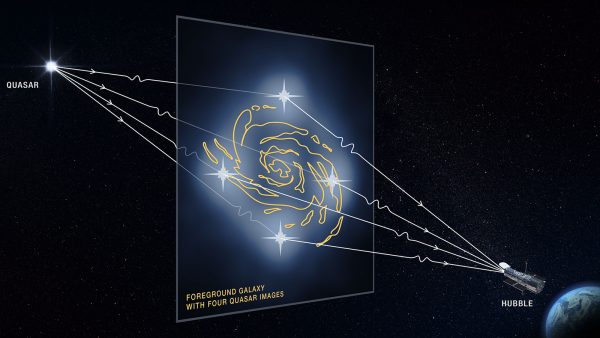

Hubble has imaged cosmic mirages, in the form of gravitationally lensed quasar images, to measure fundamental properties of the universe.

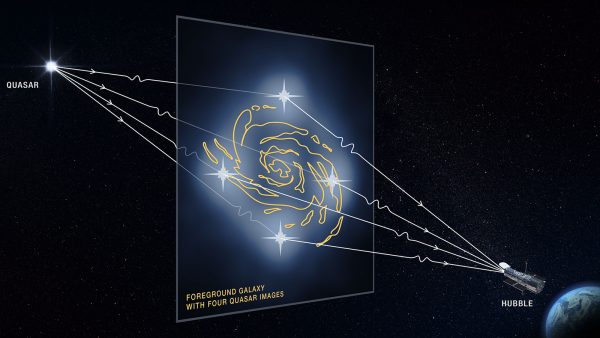

This graphic illustrates how, with just the right alignment, the mass in a foreground galaxy can alter the path of light from a faraway quasar.

NASA / ESA / D. Player (STScI)

The Hubble Space Telescope, which will celebrate its 30th birthday this April, has imaged cosmic mirages that yield two remarkable cosmological results. One constrains the nature of dark matter, the other further deepens the controversy about how fast the universe is currently expanding.

Two teams of astronomers presented the two results at a meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Honolulu. “It’s incredible that, after nearly 30 years of operation, Hubble is enabling cutting-edge views into fundamental physics and the nature of the universe that we didn’t even dream of when the telescope was launched,” said Tommaso Treu (University of California, Los Angeles, UCLA) in a press statement.

The two Hubble breakthroughs stem from meticulous observations of gravitational lenses – a kind of cosmic mirage created when gravity bends light. In these cases, the background light comes from a quasar, the luminous core of a galaxy containing a supermassive black hole. General relativity explains how a massive foreground galaxy — if it’s aligned just right — can split the light from such a quasar into four individual images. Moreover, gravitational lensing may enhance the apparent brightness of these images. Astronomers can then study the mirage, sometimes called an Einstein’s Cross, to measure fundamental properties of the universe.

Dark Matter Clumps Are Small

In the first study, led by Anna Nierenberg (NASA/Jet Propulsion Laboratory), Hubble studied eight quasars, whose light has traveled some 10 billion years; each one is quadruply lensed by a foreground galaxy about five times closer.

Each of these snapshots shows four distorted images of a background quasar surrounding the core of a massive foreground galaxy. The gravity of the foreground galaxy magnifies the quasar, an effect called gravitational lensing.

NASA / ESA / A. Nierenberg / T. Treu

Based on the lens geometry, astronomers can calculate the expected relative brightness of the four images, explained team member Daniel Gilman (UCLA). But such calculations assume that mass is smoothly distributed throughout the lens halo. In reality, however, the light-bending effects of dark matter clumps in the lens galaxy’s halo will change these expected values.

“The number and dimensions of these dark matter clumps strongly influence the relative brightnesses of the quasar images,” says Gilman. He compared the effect to cracks and blemishes on the surface of a magnifying glass, which would alter the brightness of images observed through the glass. The Hubble data indicate that the dark matter clumps tend to be relatively small, just one-hundred-thousandth the total mass of our Milky Way galaxy.

The result rules out the existence of warm dark matter, the idea that dark matter consists of “warm” (fast-moving) particles. Some cosmologists have suggested that dark matter might be warm because dark matter searches for cold (or more slowly moving) particles have turned up empty. But fast-moving particles have a hard time clumping together in small, low-mass concentrations.

According to Nierenberg, the Hubble observations constitute the strongest evidence yet for cold, low-velocity dark matter. The results were published in the December 24th Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society and also appearon the arXiv preprint server.

Cosmological Expansion Controversy

In the second study, astronomers on the team known as H0 Lenses in COSMOGRAIL’s Wellspring (H0LiCOW) focused on the “flickering” of quadruply lensed quasars.

True luminosity variations of the quasar — most likely caused by the varying activity of the central black hole — show up at different times in the four images. That’s because to produce each image, the quasar’s light follows a different path to the observer, and each path is a slightly different length. The time delays for the longer paths, combined with a map of the way mass is distributed in the foreground galaxy, yield a unique three-dimensional picture of the gravitational lens. As a result, astronomers can measure precise distances to both the quasar and the lensing galaxy. Moreover, these values are completely independent of other distance measures.

Distances are crucial for measuring the current expansion rate of the universe. Astronomers typically estimate a galaxy’s distance by its redshift, which measures how the wavelength of light stretches as it traverses expanding space. But to understand how fast space is expanding, astronomers need a distance measure that’s independent of redshift — that’s what the lensed quasars provide.

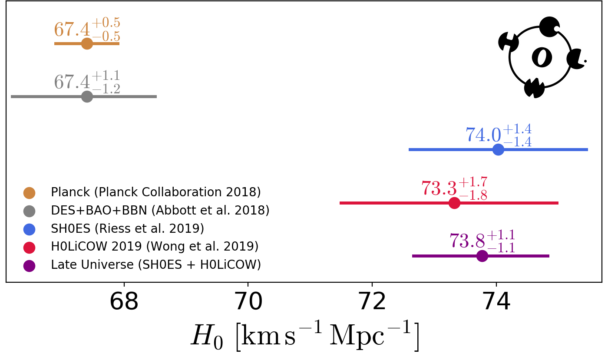

The H0LiCOW team uses the new Hubble data to obtain the most precise value of the current expansion rate yet obtained from gravitational lens studies: 73 kilometers per second per megaparsec, with an uncertainty of 2.4 percent.

This value stands firmly on one side of an ongoing debate on how fast the universe is currently expanding. Estimates based on objects in the relatively nearby universe show the current expansion rate, termed the Hubble Constant, to be 74 km/s/Mpc. However, the dark energy-cold dark matter theory that successfully models the composition and evolution of the universe, combined with precise measurements of the cosmic microwave background emitted shortly after the Big Bang, puts the Hubble Constant at 67 km/s/Mpc.

The H0LiCOW collaboration analyzed six multiply-imaged quasar systems, measuring the current expansion rate of the universe to be between 71.5 and 75 km/s/Mpc. This value is inconsistent with estimates obtained from modeling of the cosmic microwave background.

H0LiCOW Collaboration

Folding in the results from the gravitational lensing study, the tension is so strong, says team member Geoff Chih-Fan Chen (University of California, Davis), that the term “crisis” is fully justified.

The H0LiCOW team, led by Sherry Suyu (Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics, Germany), will publish these latest results in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. A preprint is available on the arXiv server.

Unsolved Riddles

The Hubble results shed new light on two cosmological riddles, but they don’t yet provide final solutions.

Yes, we may now conclude that dark matter must be cold, but the true nature of the invisible stuff is still a mystery. Likewise, while we now have strong additional evidence for a discrepancy between observations and predictions of the current expansion rate of the universe, it’s still unclear how this puzzle may be solved.

Studies of additional gravitationally lensed quasars will greatly add to a better understanding of these cosmological conundrums. Many lensed quasars are showing up in ongoing surveys like the Dark Energy Survey and Pan-STARRS, and many more are expected to be found by the NSF Vera C. Rubin Observatory (formerly the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope). Meanwhile, Hubble’s successor, the James Webb Space Telescope, will provide even more precise measurements of lensed quasars, further lowering the uncertainty in the results.

Further Reading

Read about the escalating controversy on the current expansion rate of the universe in Govert Schilling’s article “Constant Controversy,” which appears in the June 2019 issue of Sky & Telescope.