2 Studies, 1 Planet! Inside a Race to Discover a Water Vapor World – Space.com

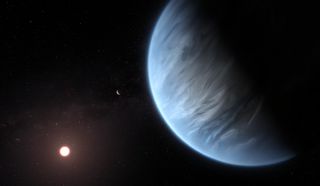

Water vapor, and likely clouds that rain liquid water, have been discovered in the atmosphere of an exoplanet that lies in the habitable zone of its star. But there’s an issue.

While the discovery broke late Tuesday night (Sept. 10) in a paper posted to the preprint server arXiv.org, a second, peer-reviewed paper was published yesterday (Sept. 11) in the journal Nature Astronomy that also showed the detection of water vapor in this planet’s atmosphere. Both of these studies used the observations made by the team who published first, on arXiv.org.

In short, researchers made a major discovery — water vapor and likely liquid water clouds in the atmosphere of an exoplanet called K2-18b — based on data they collected using the Hubble Space Telescope. But another team took and used some of that data to reach similar conclusions.

Video: Water Vapor Discovery in Exoplanet K2-18b Atmosphere

Related: These 10 Exoplanets Could Be Home to Alien Life

Often, researchers will publish their findings and then afterward, another team will take their data to independently replicate the first team’s findings or try to discover something new. But that’s not what happened here. The team who published their piece in Nature Astronomy, made up of researchers at the University College London, began using the data long before the team who made these observations published their results.

It is important to note, however, that this data was free to use and publicly available.

Hubble “data is released into the public domain as open-access data to the community,” UCL researcher Ingo Waldmann told Space.com in an email. “In addition to the data being publicly archived, we analysed it with open-source algorithms that have been publicly available on GitHub for several years.”

However, the UCL team didn’t wait all that long to take that data and submit their study. They submitted their study just 17 days after the team who made the observations received their data, principal investigator of the study published first, Björn Benneke, a professor at the Institute for Research on Exoplanets at the Université de Montréal, told Space.com.

Now, the studies do not draw identical conclusions and are different in a number of ways. For instance, the UCL study released yesterday refers to the exoplanet as a “super-Earth.” The authors of the study published first consider this label to be misleading and instead refer to the planet as a sort of “mini-Neptune,” Benneke said.

Additionally, only the study led by Benneke provides evidence of a liquid water cloud deck in the atmosphere of the exoplanet.

But, while they are not identical, both studies use data collected by Benneke’s team and draw at least one major overlapping conclusion: that water vapor exists in this exoplanet’s atmosphere.

The two studies

In a study published Sept. 11, 2019, researchers at the University College London released this image to illustrate the detection of water vapor in the atmosphere of exoplanet K2-18b.

(Image credit: ESA/Hubble, M. Kornmesser)

First, a large, international team led by Benneke published their discovery of water vapor and likely liquid water clouds in the atmosphere of exoplanet K2-18b late Tuesday night (Sept. 10) on pre-print site arXiv.org, where scientists can share studies before they are released in peer-reviewed journals. Peer-review is a process in which a study is evaluated by scientists in a similar field to ensure it meets a publication’s standards for research. For example, Nature’s peer-review process is detailed here.

The pre-print study on arXiv.org is here and has also been submitted to the Astronomical Journal.

The London-based team, which published their work Wednesday (Sept. 11) in the peer-reviewed journal Nature Astronomy, used Hubble data collected by Benneke’s team, which is cited in their paper, to detect water vapor in this exoplanet’s atmosphere.

The London team detailed their study with reporters during a news conference on Tuesday under a media embargo. In that arrangement, reporters agree to publish news stories at a certain time in return for a sneak peek at the research. The system is designed to give reporters the lead time necessary for more thorough and accurate coverage of high-profile studies.

You can see the Nature Astronomy study here.

Chasing exoplanet K2-18b

So, what exactly happened? Here’s what we know.

In 2015, NASA’s Kepler Space Telescope discovered the exoplanet K2-18b, a strange exoplanet about twice the size of Earth and eight times as massive that lies in the habitable zone of its star, 110 light-years from Earth.

Soon after, Benneke put in a request to observe the planet with the Hubble Space Telescope and find evidence of a liquid water cloud deck on the exoplanet, he told Space.com. Time with Hubble and other major telescopes and observatories is precious and is awarded to specific projects after researchers submit thorough proposals. During some proposal cycles, Hubble receives five times the number of requests that it can grant.

Benneke’s team found evidence of water vapor in K2-18b’s atmosphere with these observations some time ago, Benneke said. The team then continued to analyze the data to find evidence of liquid water clouds, which they did.

Benneke’s team observed the exoplanet transiting in front of its stellar parent, a red dwarf star, from 2016 through 2018. They then spent the next year analyzing this data to come to the complex conclusions detailed in their piece.

Related: Water Vapor on Exoplanet K2-18b Is Exciting — But It’s No Earth Twin

During that time, the UCL researchers used this data and performed similar analyses and, like Benneke’s team, detected water vapor in the exoplanet’s atmosphere. However, Benneke’s paper includes additional details about the planet itself and provides evidence for liquid water clouds, and possibly even rain.

“The paper under embargo says that the data set they used has a PI Björn Benneke. The PI would have designed and competed for the Hubble observations. The fact that the PI was not on the author list means another team used the publicly available data in a competition,” Sara Seager, an astronomer, planetary scientist and professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who was not involved in either study, said in an email to Space.com.

Now, remember, the data was publicly available for anyone to use.

“Technically it’s not illegal to take this data,” Benneke said to Space.com.

Additionally, he added, the fact that the London-based team also detected water vapor, “it’s not a surprise because, effectively, our team did a very good job and these observations, they were all executed very well by NASA and the space telescope … it doesn’t require too much from another team … to just take the data and analyze them the same way.”

In part, this is good, he continued, in that it shows that two teams “have looked at the data and demonstrated both independently that there is the signature of water absorption on this planet.”

But, Benneke said, “I’m not very excited at the fact that they just took our data … they didn’t contact me at all about this.”

In short, Benneke and team thought they were on track to a unique discovery, only to find their data had helped another team reach a similar, overlapping, conclusion.

The race to publish

In science, just as in sports, there is always a race to be first.

“In exoplanet science there are a lot of cases where two competing papers on the same topic are put out simultaneously, but not usually with a PI’s data set where the standard practice is a common courtesy to leave the data analysis and publication for the PI’s team,” Seager said.

That departure from standard practice can make the London team’s actions seem more like an act of competition. But to reiterate, they did not cross any legal lines in doing so, as they used this Hubble data only after a window of time (a specified “proprietary period”) which is meant to serve as a buffer to allow the science team who made the original observations publish their findings first.

“All the data used for the UCL study are publicly available on the STScI MAST archive — indeed, the observations have been publicly archived,” Waldmann said in a statement emailed to Space.com.”

“We are aware of reports of other researchers publishing a study on the pre-print platform, arXiv, on Tuesday 10 September reporting similar findings. As it is not a peer-reviewed study, we cannot comment until it has been validated. If the study passes peer-review, it would strongly confirm our results, which is fantastic.”

This strange situation is almost as strange as K2-18b itself. “Business-as-usual” procedures certainly haven’t applied to these discoveries.

But, while this exoplanetary debacle might ruffle a few feathers in the scientific community, the findings from both of these papers is a huge step forward in our understanding and knowledge of exoplanets and the search for water beyond Earth and beyond our solar system.

Editor’s Note: A previous version of this article stated that Benneke’s team made observations in 2016 and 2017, but they also made observations in 2018.

Follow Chelsea Gohd on Twitter @chelsea_gohd. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.