New Telescopes Will Help Us SETL – Nautilus – Nautilus Magazine

Silence. Eerie, unnerving silence.

Despite all our work, all our straining efforts to hear a whisper from the void, that’s all we have. Silence.

More than 60 years ago, the pioneering radio astronomer Frank Drake and his colleagues laid the groundwork for what astronomers around the world would transform into an ambitious idea: SETI, the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence. The rationale was simple. As humanity progressed in its technological development, we eventually struck upon the idea of radio communications. These waves of electricity and magnetism weren’t only capable of wrapping messages around our globe, they could also pierce into the depths of the galaxy itself. And if any other intelligent beings were somewhere out there, they would likely be creating their own radio chatter.

The deafening silence so far suggests that we are alone.

This quest for extraterrestrial intelligence continues today, largely ignored by professional astronomers and kept alive in large part by generous private donations. Despite the extraterrestrial cold shoulder, proponents of SETI (by which I mean the general field, not specifically the institute by that name) argue that our efforts thus far have barely scratched the surface, hemmed by using radio dishes to scan a relatively miniscule band of radio wavelengths in tiny slivers of the sky, for brief periods of time, among just a small bubble of nearby stars.

All life, even humble, simple single-celled organisms, can be loud in its own way.

Perhaps it’s been quiet because intelligence is not bound to follow the same technological track as us—cultural development, just like evolution, has no prescribed course after all. Or perhaps other civilizations only briefly broadcast in radio signals before switching to other, more targeted and efficient methods of communication. Perhaps the gulfs of time and space separating intelligences have simply been too vast to cross yet.

Or perhaps we truly are alone.

But the likely answer is that most other life forms out there don’t meet the capital “I” of SETI’s target: “intelligence.” This approach of listening for alien peers, which dates back to the 19th century, was founded on the idea that intelligent life is loud and messy, broadcasting its existence—even unintentionally—for any careful listener to discover. And those noises, those disruptions in the expected patterns of the universe, could theoretically be easy for us to spot—even with relatively rudimentary 20th-century radio telescopes.

But all life, even humble, simple single-celled organisms, can be loud in its own way. And with new and near-term technology, we are now better poised than ever to detect even the simplest biology far, far afield. Not radio blasts, but subtle signatures. The traces not of equals, but of any life.

So the time has come to SETL: Search for Extraterrestrial Life.

Indeed, the SETL program (which by no means is an official or even community-recognized acronym, just a joke I never get tired of telling) has, in the past decade, become among the fastest growing areas in astronomy, combining the latest insights from astrophysics, chemistry, and biology to try to find any signs of life whatsoever in an alien world. (Indeed, even the SETI Institute itself has now included it in their portfolio of research.)

Without the loudness of alien technological signals, it seems like a hopeless pursuit to search for biological whispers among the approximately one trillion exoplanets in the Milky Way. The ultimate needle in the cosmic haystack.

But the SETL approach has two related advantages over one searching for technologically advanced civilizations. One, the likelihood of success is much higher. It stands to reason that intelligent life would be much rarer than simpler life. Life has existed on our own planet for about as long as we’ve had a planet, and we only developed stone hand axes, let alone radio technology, basically yesterday. So there are probably many more worlds out there teeming with some form of life, making those planets an easier catch.

Second, one of the great hallmarks of life in any form is its ability to completely mess up a planet. Without life, worlds reach a certain equilibrium state governed by the simple physics of distance from a parent star, starting composition, and rational chemical and geologic processes.

The time has come to SETL: Search for Extraterrestrial Life.

But life as we know it (and, caveat again, we only have one example to work with here) just loves to throw everything out of balance. (No radio transmitters required.) The classic example on Earth is the presence of abundant oxygen in our atmosphere. Sure, oxygen is ridiculously common in the universe, and there’s plenty of it on Earth, bound to silicon to make rocks or carbon, for example. But loose oxygen is very unstable, and without life, there would be little to no oxygen in our planet’s atmosphere. There’s simply no physical or chemical or geological process that generates it in abundance and keeps replenishing it. But there is a biological process underway here: photosynthesis, which creates an atmosphere that is remarkably different than it would be without life.

Of course this method isn’t foolproof. Methane is also a common byproduct of life on Earth, created by decomposing organic matter—and billions of cow farts. There’s certainly more methane on the Earth than there should be (which is somewhat of a problem for us because it’s a greenhouse gas). Our neighbor planet Mars also has a curious slight abundance of methane in its paltry excuse of an atmosphere. The methane on Mars even undergoes seasonal variations, just like on Earth.

Nobody thinks that Martian cow farts are responsible. But, even after more than a decade of relatively close-range study, there is no consensus as to what exotic geochemical process underlies the Martian methane mystery.

So the search for life abroad in the cosmos likely won’t hinge on a single, eureka-like moment of discovery, but rather the slow and deliberate accumulation of evidence.

And that evidence will come, likely not in the form of radio waves, but light.

When we spot an alien world, we now have several methods of sampling its atmosphere from afar. Sometimes the planet will cross between our view and its parent star. When it does, we can see how the star’s light changes subtly as it filters through that planet’s atmosphere, providing spectral features, the fingerprints of various elements and molecules.

If a lucky alignment for visible light isn’t in the cards, we can search in the dark. Using a coronagraph to block the light of the parent star, researchers can observe the infrared radiation from the body of the planet itself or from starlight reflected off it. Either way, we get another way to taste its atmosphere.

Astronomers have already used this technique to find evidence of carbon dioxide and methane on other worlds. So far, however, there has been no smoke signal of life.

Nobody thinks that Martian cow farts are responsible for the methane on Mars.

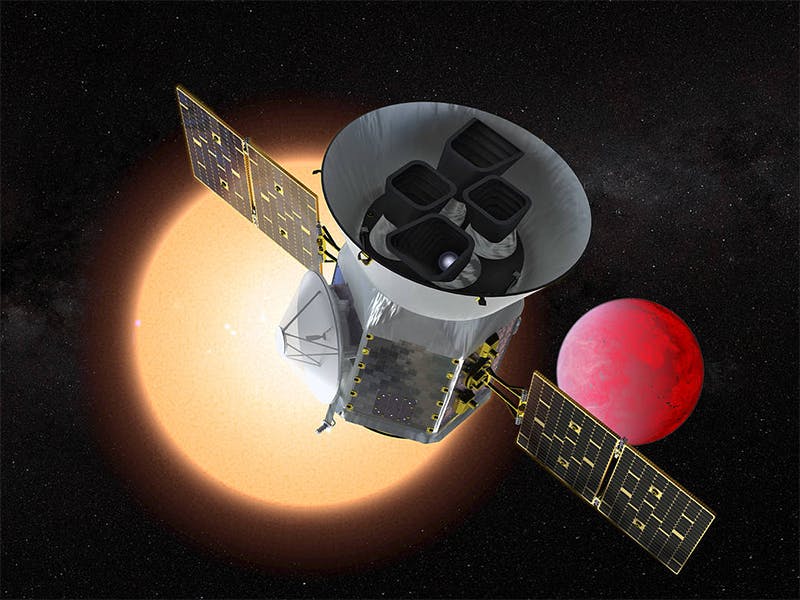

While NASA’s ongoing Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite and shiny new James Webb Space Telescope can get us some early clues about where to focus our attention, we are going to need much bigger and more complex instruments to pick up a broader range of potential biosignatures.

To really capture life’s whiffs on another world, agencies around this world are developing and proposing slews of breathtakingly ambitious new equipment and missions.

NASA is embarking on the early phases of creating a new space-based telescope specifically to search for habitable worlds. That instrument, which has a target launch date in the 2040s, will share a design plan with the (hopefully then-outdated) James Webb. But it will also bring along a powerful coronagraph, which will allow the mega-observatory to examine especially promising exoplanets. Those readouts won’t be the bare sketches that we get today, but a much more complete census of the chemical mixture of those alien atmospheres.

The European Space Agency is in the midst of launching a trio of satellites to join the James Webb in its hunt for any life. Each of them will have slightly different but overlapping planet-hunting and planet-characterizing capabilities. The small CHEOPS mission, launched in 2019, is designed to accurately measure the diameter of exoplanets. Combined with knowledge of mass, we get the density, which immediately narrows down the range of possible compositions (and friendliness to life). PLATO, expected to launch in 2026, will identify up to 1 million exoplanets, with optics and instruments especially designed for hunting Earth-like worlds in Earth-like orbits around sun-like stars. Lastly, ARIEL, likely launching in 2029, will be a faithful companion to the James Webb, with similar capabilities but able to dedicate more time observing individual worlds.

Other nations, including China, have proposals floating around as well. The Chinese Space Agency recently released plans for a space-based observing platform containing a whopping seven telescopes to launch as early as 2026. Named Earth 2.0, that array of telescopes gives the observatory a huge advantage in field of view, allowing it to see planets around many more stars—as many as 1.2 million suns. Promising candidate worlds could then be probed for signs of life with a more focused analysis.

And if we do find life out there, quietly circling around another sun?

It’s impossible to say what the implications of such a momentous discovery would be. Surely a few prizes, including the Nobel, would be handed out. The conclusive demonstration of life arising elsewhere would both settle and raise scores of questions, some scientific, others philosophical. But science will have the opportunity to rise to the challenge, with the development and deployment of new generations of telescopes and observatories to better understand our newfound neighbors, however humble they may be.

And for me, that would be more than good enough.

Paul M. Sutter is a research professor in astrophysics at the Institute for Advanced Computational Science at Stony Brook University and a guest researcher at the Flatiron Institute in New York City. He is the author of Your Place in the Universe: Understanding our Big, Messy Existence.

Lead image: Skorzewiak / Shutterstock